DIVISION FOUR.

THE FUGUE.

Introductory.

112. The Fugue differs from the Invention chiefly in being a more strict and serious contrapuntal form. Review par. 37. While the Invention is subject only to the general conditions of contrapuntal treatment, the Fugue, on the other hand, involves certain special conditions and limitations.

These special qualities, which distinguish the Fugue, are as follows:

(1) The Subject or Theme of a Fugue is usually more extended, and has a more definite form, than the “Motive”;

(2) The Subject is first announced alone, in a Fugue, unattended by auxiliary tones;

(3) During the first Section, or Exposition, the Subject is (as a rule) announced alternately in the Tonic and Dominant keys, i.e., it is imitated alternately in the 5th and 8ve; and

(4) There is, throughout, less freedom of detail, and greater seriousness of character and manipulation.

The Fugue-Subject.

113. The thematic germ of a Fugue is called “Subject” or “Theme.”

The former term is used in a specific sense; the term “Theme” as a general designation of the thematic basis.

a. It is, with rare exceptions, definite in form, being either a complete Phrase or (more rarely) Period, and closing as a rule with a distinctly cadential effect. Its length is optional, — from one large measure (Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 17) up to 6, 8, or even more measures (Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. II, Fugue 15; Organ Comp., Peters compl. ed., Vol. III, Fugues Nos. 3 and 8).

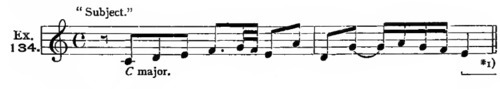

b. Generally it begins either upon the 1st, 3rd, or 5th scale-step of the key; but in any case the Tonic note should appear near (if not at) the beginning. It may begin upon an accented beat, or upon the preceding unaccented beat; but by far the best and most common practice is to begin the Subject with a brief rest, i.e., immediately after an accent (Ex. 134).

It ends, frequently, upon the 3rd scale-step, or upon the Tonic (more rarely upon the Dominant), of the principal key; or upon the Tonic or 3rd step of the Dominant key. Other cadences are possible, but very rare. The final tone falls usually upon an accented beat, and produces a decided cadential impression; but there are exceptions to this rule, and it is sometimes difficult to determine precisely where the Subject terminates (see Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 9,— doubtful whether the Subject ends on 3rd beat of second measure, or on 1st beat of third measure). The Subject may contain transient modulations, in its course, but can scarcely end in any other than the principal, or the Dominant, key; possibly in the Relative major, from minor.

c. As Subject of a Fugue, and as complete melodic sentence, it should be distinctly individualized. Its melodic and rhythmic contents must be serious, but characteristic, and pregnant (susceptible of manifold polyphonic manipulation); and its delineation must be distinct and moderately striking, — to the exclusion of vagueness, of a too lyric melodic form, but also of eccentricity. Sequences are seldom absent, in good Subjects; the harmonic basis is clear, natural, and forcible; and there is usually at least one salient rhythmic feature (an effective tie, syncopation, or contrasting figure). The compass of effective Subjects seldom runs beyond an octave. Review par. 38a.

EXERCISE 34.

A. Inspect, minutely, every Fugue-Subject in both volumes of Bach’s Well-tempered Clavichord, with reference to each detail given above.

B. Write a large number of original Subjects.

The Construction of the “Response.”

114. As stated above, the Subject or Theme is to appear, during the first Section (the Exposition) of a Fugue, first in the principal key, then in the Dominant key, and so on, alternately in the Tonic and Dominant registers, as far as the number of voices dictates.

The first announcement (tonic) is called the Subject proper; the second announcement (dominant) is called the Response or Answer.

115. In order to place it in the Dominant key, the Subject must be imitated in the perfect 5th above (or perfect 4th below). Hence, the fundamental rule for the construction of the Response is:

To imitate each tone of the Subject in the perfect fifth.

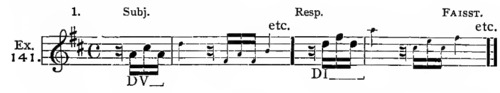

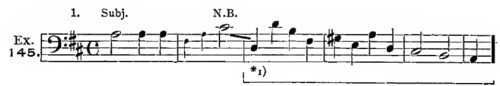

This gives what is known as the “real” Response or Answer. For example:

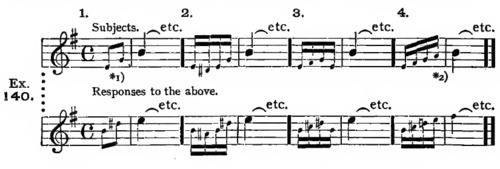

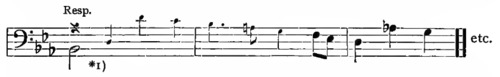

*1) The adjustment is perfect, and no circumstance exists which would necessitate an exception to the fundamental rule.

116. But this strict imitation often gives rise to awkward or abrupt modulation, and a lack of adjustment at the extremes (beginning or end) of the Response. The element invariably involved in such embarrassment is the Dominant. Hence, the first general exception to the fundamental rule is:

That the Dominant element, wherever peculiarly conspicuous in the Subject, is to be imitated in the perfect fourth, instead of 5th.

a. This applies (1) to the Dominant tone at the very beginning; or (2) near the beginning (as 2d, 3rd, or 4th tone of the Subject, especially when connected with the Tonic note); (3) to all tones inseparably connected with this initial Dominant (as embellishment, repetitions, and the like); (4) to a strong Dominant chord-impression at, or very near, the beginning; (5) to the cadence in the Dominant key (at the end of the Subject); and (6) to all tones that pertain inseparably to this final Dominant. All such tones should be imitated in the perfect 4th.

This is called the “tonal” Response.

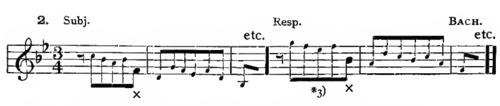

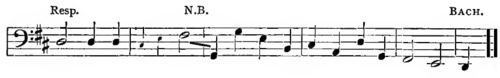

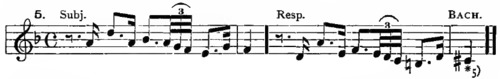

117. a. The Dominant note at the beginning. For illustration:

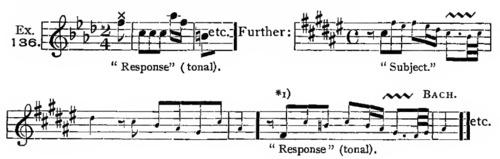

*1) The Dominant note at the very beginning would, if answered in the perfect 5th, transfer the Response abruptly, and bodily, into the Dominant key (c minor). Thus:

The first tone, g, would not adjust well with the cadence tone of the Subject (a♭). In a word, this initial g is the Second-dominant (Dominant of the Dominant) in the key of f minor thus far pursued; and while this comparatively remote tone, or any other, can be reached in time, it is certain to sound abrupt at the very beginning of the Response. Therefore the above Subject is imitated as follows, the first (Dominant) tone in the 4th, and the remainder, as usual, in the 5th:

By this means the Response is retained for an instant in the original key, until perfect adjustment, at the beginning, is secured. It is called the “tonal” Response because of this (at least temporary) adherence to the tonality of the Fugue; the Tonic elements being answered by the Dominant, and the Dominant elements (where salient) by the Tonic (imitation in the 4th).

*1) All large notes indicate the imitation in the 4th; the small notes that in the 5th.

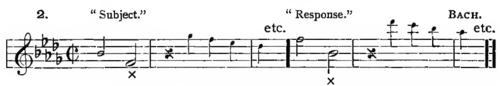

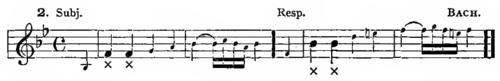

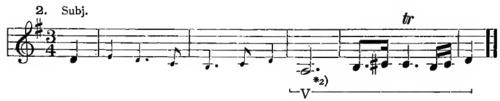

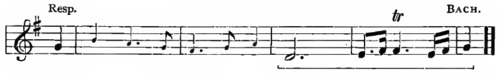

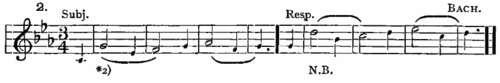

b. The Dominant note near the beginning:

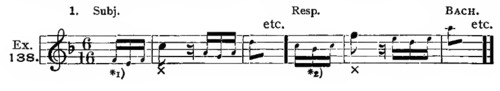

This always applies to the Dominant as second note of the Subject, when it follows the Tonic; and, in case the initial Tonic note is embellished, it may be the 3rd or 4th tone of the Subject. Thus:

*1) The initial Tonic (f) is simply embellished; therefore the Dominant (as 4th tone, c) is near enough to the beginning to be the second essential tone.

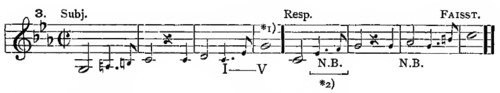

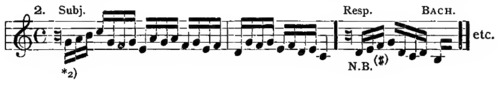

*2) The second tone of the subject (e) is here imitated in the diminished 5th (b♭). Similar substitutions of the diminished or augmented 5th (and 4th) for the perfect 5th (and 4th) are quite common, and are due to the very same principle that gives rise to the general exception under discussion (par. 116). See Note to Ex. 136. Here the b♭ confirms the principal key, F major. — See also Ex. 146, No. 3.

*3) Same as Note *2).

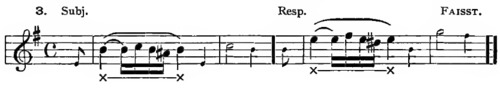

c. Repetitions or embellishments of the Dominant, at or near the beginning:

Or, adding to this last Theme (Ex. 139-3) various embellishments of the initial Tonic (as in Ex. 138), the results would be:

*1) In every case (excepting No. 4) this g is imitated in the augmented 5th, (d♯), because of the principal key. Comp. Ex. 138, Note *2).

*2) No. 4 is a regular (real) Response. The tone a in the Subject changes the whole situation. Partly because the a does not pertain to the initial Tonic, and partly for reasons given in par. 118, the Dominant b must be answered in the 5th. See further Ex. 145, No. 6.

d. A cluster of tones at (or very near) the beginning, that constitute a very obvious Dominant chord:

e. As declared in par. 116a (3), all tones that pertain inseparably to the Dominant at or near the beginning of the Subject, share with it in the exception to the rule. To this class belong the repetitions and embellishments illustrated in Ex. 139; also a diatonic run from the initial Tonic down to the Dominant; thus:

Possibly also the nearly continuous run from Tonic up to Dominant

This comes under the head of Ex. 140; but there is a subtle distinction between it and Ex. 140, No. 4 (which it closely resembles), that is left to the student’s analysis.

f. Finally, the Dominant key, at the end of the Subject, when introduced by a palpable modulation, is subject to the exception. Thus:

*1) An important question in connection with the final Dominant key is, how far back from the end the imitation in the 4th is to extend. It is best solved according to the principle of par. 117e; — all tones that are inseparable from the final Dominant, as belonging obviously to the total impression of the “Dominant key,” are imitated in the 4th. In the above case the tonal imitation begins at the very point where the modulation was made, in the Subject; and, further, at the rest which marks a semicadence.

*2) Here Bach appears to regard the a (3rd measure of Subject) as inseparable from the following modulatory movement into the Dominant key, and therefore begins the imitation in the 4th at that point.

g. The puzzling questions can, in many instances, be determined only by carefully testing the effect, and preserving a good, smooth, modulatory and melodic result. The trouble consists, as stated, simply in deciding which tones are inseparably connected with the Dominant; and this may depend upon the melodic structure, the modulation, rhythm, or other circumstances bearing upon the characteristic formation of the Subject as a whole. Therefore, the ultimate decision is, here and elsewhere, very often indeed a matter of common-sense judgment, or individual taste.

118. Partly in keeping with this last idea, and partly for general reasons, a third rule must be observed, which constitutes in a sense an exception to the rule of tonal imitation (par. 116), and therefore reverts partially to the fundamental rule, namely:

Under no circumstances shall any characteristic feature of the Theme be violated.

Consequently, neither the real nor the tonal imitation can be insisted upon at any point where they threaten any tone or figure of the Subject that is significant or characteristic. For illustration:

*1) These tones are all harmonically inseparable from the Dominant modulation; and the preceding interval (falling 7th) is so characteristic that it, too, is included in the tonal imitation.

*2) This g is a conspicuous Dominant note, near the beginning; but it is answered in the 5th, because of the sequential formation of the Theme.

*3) Bach evidently regarded this d (Dominant near the beginning) as an essential harmonic factor of his Theme, and imitates it in the 5th to preserve the triad-effect of the first figure.

*4) A remote key, but unavoidable because of the definite chromatic character of the Subject.

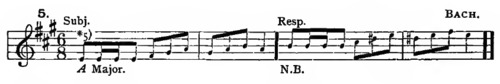

*5) Dominant as first tone,—imitated in the 5th, with its repetitions, apparently because of the structure of the whole Theme. Comp. Ex. 149, Note *2).

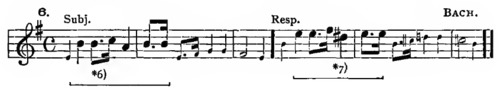

*6) To Bach this was a tone-group inseparable from the Dominant (b), and therefore the whole figure reappears in the 4th.

*7) Augmented 4th; see Ex. 138, Note *2).

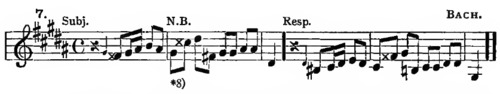

*8) This peculiar leap of an Augmented 4th is an inviolable trait of the Theme, and therefore it renders the foregoing tones likewise inseparable from the final Dominant key, — back to the second tone of the Subject.

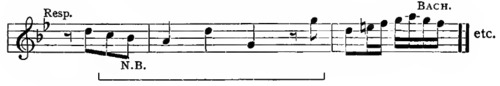

119. The single Dominant note at the end of a Subject is not to be imitated in the 4th (tonal), unless it is strongly suggestive of the Dominant key, or Dominant chord:

*1) This final Dominant note is more strongly indicative of the Dominant chord than those of the preceding examples, because it occurs at the bar, where a change of harmony (from the foregoing I) is expected. Therefore, it is imitated in the 4th, — although the 5th (d) would have been entirely defensible.

*2) At the points marked N. B. the necessity of using diminished (instead of perfect) 5ths, in order to obtain a sensible and natural total modulatory result, is strikingly illustrated. Comp. Ex. 138, Note *2).

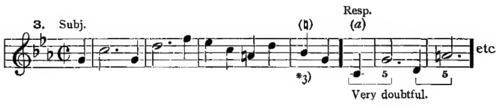

*3) This case is similar to No. 3, being an accent, and therefore suggesting a change of harmony (from I to V). Besides, the whole Theme is so brief, and so nearly all Tonic, that the final Dominant seems near enough to the beginning to demand tonal treatment (par. 117b).

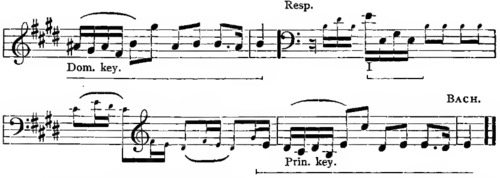

120. a. When the Theme begins with the Dominant note, and also ends in the Dominant key, it may be possible, and necessary, to imitate the initial Dominant in the 5th. Thus:

*1) As the Dominant key has already been reached, there is no danger of imperfect adjustment, and therefore the “real” imitation is entirely feasible.

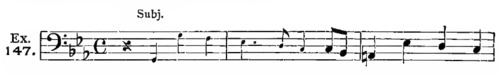

b. Further, when the Dominant effect prevails decidedly through the whole or a great part of the Theme, it may be necessary to imitate it in the 4th throughout. Thus:

In both of these cases all that is not actually Dominant appears to be inseparable from the prevailing Dominant effect.

Miscellaneous.

[ed. note: The A♭ on beat 4 of measure 3 in example 149-3b is almost certainly a typesetting mistake, meant to be A♮. I have used A♮ in the audio example.]

*1) This initial Dominant is answered in the 5th (contrary to par. 116a), because of the characteristic formation of the Theme. Comp. par. 118.

*2) The initial Dominant is here simply one of a series of unimportant passing-notes leading into the Tonic, and is therefore answered in the 5th. Further, Bach chooses f♮ for the 3rd tone of the Response (instead of the expected f♯), in order to preserve for an instant the impression of the original key.

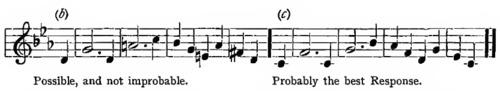

*3) In case Response (c) were to be chosen, this would be b♮ in preference to b♭. Otherwise, the latter is more probable.

*4) The final tone is imitated in the augmented 4th, to preserve closer relation to the original key,—probably because the Subject is brief. Compare Ex. 138, Note *2).

*5) Same as Note *4).

*6) The striking modulation into the Dominant key, so near the beginning, must be answered in the 4th, — similar to par. 117d.

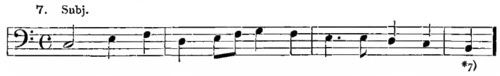

*7) The prominent Leading-tone, when absolutely indicative of the Dominant chord (as here), and not merely an embellishing note of the Tonic (as in Ex. 138, No. 1, 2nd tone), is subject to tonal imitation, with all that is inseparable from it. Comp. par. 117d.

*8) Like Note *7).

EXERCISE 35.

A. Analyze all the Responses in the Well-temp. Clavichord of Bach.

B. Write the Responses to all the original Subjects invented in Exercise 34. And invent a number of new Themes (and Answers), with reference to the above traits.