CHAPTER XVIII.

The Progressive Canon.

190. In the Progressive Canon the same principle of strict continuous imitation prevails; but any other interval (or species) of imitation may be used quite as well as the octave; and the time-interval is generally much shorter, — i.e., the risposta follows the proposta, or Leader, earlier than in the Round; and, finally, there is less distinctness or regularity of form, and no such characteristic recurrence of the leading sentence, — excepting the distinctive return to the beginning necessary when the 3-Part Song-form is chosen, or when Part I is to be repeated.

The Two-Voice Canon, Unaccompanied.

191. In the 8ve. Either part may be chosen as Leader. A simple melodic motive is devised, very similar in contents and character to the Motive of an Invention or a short Fugue-subject, but without cadence. Its length depends upon the time-interval between Leader and Follower. This is most commonly one measure, sometimes two measures, or one-half measure in any compound rhythm; more rarely one beat, or any other uneven fraction of a measure, for it is desirable that the prosodic effect of Leader and Follower (disposition of accents) should agree.

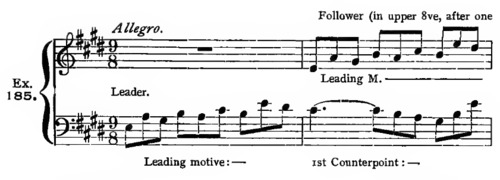

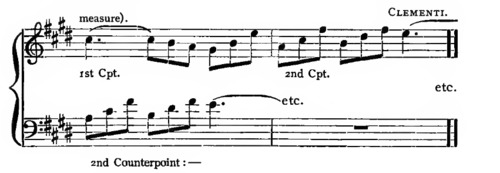

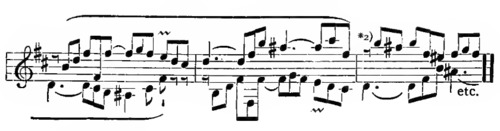

This leading motive is then imitated in the other voice, either an 8ve higher or lower, while the Leader proceeds with a contrapuntal associate devised in strict conformity to the rules in par. 35a, which review. The Follower imitates this Counterpoint, while the Leader again proceeds with a new one, — and so on, to the end of the Canon. If, for instance, the time-interval is one measure, the contents of every (or any) measure in the Leader will be literally reproduced in each following measure in the Follower; — though a duet, the contents of one voice alone will represent the entire melodic material of the composition. For illustration:

192. There are two characteristic difficulties persistently present in the constructive process of an unaccompanied Canon in the 8ve, namely:

a. The difficulty of avoiding monotony.

The 1st counterpoint is, presumably, a peculiarly fitting associate of the leading Motive. When it reappears in the Follower (3rd measure of the above example) it is necessary to devise an equally good, but new, associate, as 2nd counterpoint, whereby the natural temptation to fall back upon the leading M. must be resisted. In other words, constant care must be taken to use new contrapuntal intervals in successive measures; also intervals occasionally foreign to the key, in order to effect necessary modulations. But no liberties are to be taken with the Follower; in the 8ve-canon the imitation is absolutely strict. It is also necessary to avoid monotony of rhythm and monotony of register. All of these considerations are skilfully observed in the following:

*1) The last beat of this measure was harmonized, in the Leader (preceding measure), with b, d, and d♯; here a totally new result is obtained by using f♮, This, and the persistent evasion of the distinctive Mediant c (in this whole measure of the Leader), prepares for the unique modulation (or change of mode) into a minor, at Note *2).

*3) The diversity of register during these 5 measures is noteworthy; from the high e of the Leader to this low e a range of 4 octaves is covered.

*4) Diversity of rhythm is here effected and sustained by the heavy syncopated formation of the Leader.

b. The difficulty of obtaining intelligible form.

The student will soon discover how galling the constraint of persistent strict imitation is; every desirable melodic aim is hampered, apparently to a fatalistic degree; and this is especially palpable at the cadences, or at any other point in the structural design where it is necessary to conduct the Leader in a certain definite direction. The dogged pursuit of the Follower is in itself a circumstance that militates against clear cadential effects, because the Leader can perform no act alone.

At the same time, it is absolutely necessary (particularly at the beginning, and from time to time in later sections) to preserve, at least approximately, the effect of regular Phrase- and Period-formation; to provide for a firm cadential separation at the end of the First Part; and, in case a repetition of Part I is required, or when the 3-Part form is used, to lead the voices back to the beginning.

The best device for such recognizable (if not strictly regular) syntactic formations is a judicious use of Rests in the Leader. The rests should not be so brief as to appear breathless, or so long as to sever the continuity of the sentence (excepting at strong cadences, where a whole-measure rest may be used); nor should the rests be so frequent as to defeat their own purpose.

In a word, it is mainly necessary to impart to the Leader a good and intelligible melodic and syntactic form — as far, and as continuously, as is possible under the canonic constraint. The Follower may then be left to take care of itself, as far as the “form” is concerned. For this reason, also, it is wise to introduce from time to time some striking melodic or rhythmic figure in the Leader; not only because these contribute to the intelligibility of the form, but because they emphasize the relation of the Follower to the Leader, i.e., render the canonic imitation, as such, more recognizable. But see par. 202.

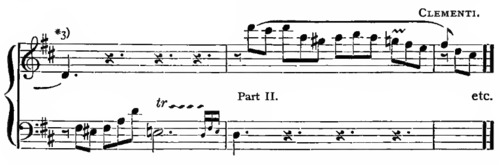

The “formation” is very distinct in the following:

*1) These rests mark the end, or semi-cadence, of the first 2-measure phrase-member.

*2) Here the second phrase begins, with the first melodic member (i.e., parallel construction, regular Period-form).

*3) Perfect cadence, marking the end of the First Part (meas. 26).

*4) This striking rhythmic figure is not only an important feature in the melodic delineation of the Leader, but also defines the canonic imitation clearly when it reappears (next measure) in the Follower.

c. The time-interval is a significant factor in the Canon, as it affects both the difficulty of structure and the recognizability of the imitation. The shorter the time-interval, the greater and more insistent is the canonic constraint. The imitatory effect can scarcely be brought out clearly when the time-interval is very brief, nor, on the contrary, can the connection between Leader and Follower be easily traced when more than two ordinary measures intervene. Long time-intervals may, however, conduce to regularity of design; for instance, a 4-measure interval is likely to resolve the Canon into a perfectly regular Phrase-group form.

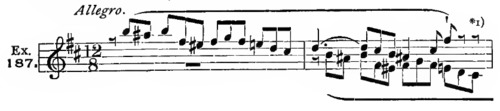

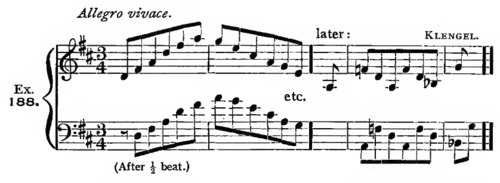

The following is a unique example of short time-interval:

d. The canonic imitation may extend to the very end, — in which case the Leader may pause, or may be a free counterpoint, during the final time-interval. Or it may be discontinued one, or several, measures before the final perfect cadence; the final measures will then assume the character of a free codetta or coda.

e. The Canon in Unison is very rare without accompaniment.

Analyze the following examples very minutely:

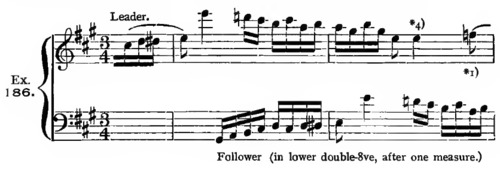

Clementi, “Gradus ad Parnassum,” Schirmer ed. (Vogrich), No. 62 (orig. ed. No. 63); 8ve, after one beat; near the end the Leader is conducted back to the beginning and repeated; therefore it is, to that extent, “endless,” but the last measure provides the perfect cadence. — No. 64 (orig. 26); 8ve, after one long measure; cited in Ex. 187. — No. 65 (orig. 67); double-8ve, after 1 measure; 2-Part form, Part I repeated (“endless”); cited in Ex. 186.— No. 67 (orig. 75); 8ve, after 1 measure; Part I “endless”; cited in Ex. 185.

Klengel, 48 Canons and Fugues, Vol. II, Canon 5; 8ve, after ½ beat; cited in Ex. 188. — Vol. II, Canon 11; 8ve, after 4 measures (see par. 192); last 16 measures free. — Vol. II, Canon 23; 8ve, after 1 measure; the first 10 measures are monotonous (see par. 192a).

Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Canon II; 8ve, after 4 measures.

Beethoven, C-minor Pfte. Variations, Var. 22; 8ve, after one beat (very slight modification).

Mozart, No. 43 (Breitkopf & Härtel, Serie 7); vocal Canon in Unison, after 2 beats; “endless,” returning to beginning after 11 measures; no cadence.

Many other examples will be cited, later, among the Accompanied Canons.

193. In the 2nd. The Follower imitates the Leader, at the chosen time-interval, either in the 2nd above or the 7th below. The latter distinction is wholly unnecessary (though customary), for, as explained in Ex. 67, Note *2) — which see, — the imitation of any letter in the 2nd will be the next higher letter, whether placed above or below the leading part.

Each canonic Interval has its peculiarities, and it is left largely to the student to discover and learn to master them.

a. Probably the most characteristic difficulty of any other than the 8ve-canon, is that of preserving the natural harmonic relations of the tonality; it is the direct opposite of that shown in par. 192a, for these varieties of the Canon are apt to be too restless, and to contain too much variety. The constant uniform shifting of the parts tends to an unvaried sequential structure which must be prevented from destroying the unity of key, and must be mitigated by the best possible collective formal arrangement. See par. 192b.

b. Good modulatory results are impossible without free use of the changes in interval-quality, defined in par. 28a, — which review, in connection with the Notes to Ex. 69. Therefore, it is entirely legitimate to substitute the major 2nd for the minor 2nd, or vice versa, at any point; or even the augmented 2nd for either. But the letter must not be changed; i.e., the interval-quantity must be respected.

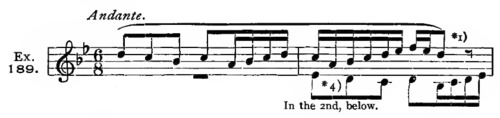

c. All the formal conditions correspond to those of the 8ve-canon. For illustration:

*1) This rest defines the syntactic arrangement of the phrase in two 2-measure members.

*2) Here a definite semi-cadence is made on the Dominant of the leading key.

*3) It is often necessary, and always permissible, to cross the parts, as here.

*4) The first 2nd is minor, the next major.

See Bach, Air with 30 Variations for clavichord, Var. 27, Part I.

Other examples will be given among the Accompanied Canons.

194. In the 7th. This is the counterpart of the Canon in the 2nd, and exhibits precisely the same peculiarities, merely reversed. For example:

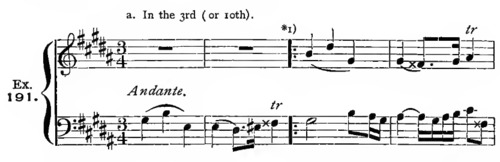

195. In the 3rd. This interval is somewhat easier to manage than the 2nd, though the same difficulties exist, and similar remedies are necessary (par. 193a and [par.] 193b).

The same applies to its counterpart, the Canon in the 6th. For illustration:

*1) At the end of Part I (meas. 27) the Leader is conducted back to the beginning, and the Part is then repeated, with 1st and 2nd ending.

*2) From “48 Canons and Fugues,” Vol. II, Canon 18. Analyze carefully. — See also Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Canon III; in 10th, — with Artificial Double-cpt. in 10th.

196. In the 5th, and its counterpart, in the 4th. For illustration:

*1) “48 Canons and Fugues,” Vol. I, Canon 19. Analyze to the end. See also Vol. II, Canon 3 (in 5th, after 2 measures).

Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Canon IV; in the 5th, with Double-cpt. in the 12th.

For an example of the Canon in the 4th, see Klengel, Vol. II, Canon 6; after 4 measures.

EXERCISE 54.

A. Two examples (major and minor, different time and tempo) of the Unaccompanied 2-voice Canon in the 8ve. Review par. 192a, [par.] 192b, [par.] 192c, [par.] 192d.

B. Examples of’ the Unaccompanied 2-voice Canon in the 5th, 4th, 3d, 6th, 2nd, and 7th. Either write one brief example of each; or a continuous example in sectional form, with a different interval in each section. Some experiments must, however, be made in 2- or 3-Part Song-form, with repetition of Part I.

Other Species.

197. The Canon in Contrary motion. Here the choice of “corresponding tones” is of great importance. Review par. 29a thoroughly. As there demonstrated, the best results are obtained either by answering Tonic by Mediant, or Tonic by Dominant.

All other conditions correspond to those of the above species. See, particularly, pars. 192b and [par.] 193a.

For illustration:

*1) The Tonic e in the Leader is answered by g♯, the Mediant, in the Follower, throughout; and vice versa — the Mediant by the Tonic (g♯ everywhere by e).

*2) “Gradus ad Parnassum,” Schirmer ed. No. 66 (orig. No. 73). Analyze to the end. It is “endless,” but with an added cadence.

See also, same work, No. 63 (orig. No. 10); exactly the same; Tonic = Mediant, after 1 measure, “endless,” but with cadence.

Klengel, Vol. II, Canon 20; Tonic = Dominant, after 2 measures.

Brahms, Händel-Variations, op. 24, Var. 6; Part I, parallel 8ve-Canon, after 1 beat; Part II, Contrary motion; Part III, again parallel.

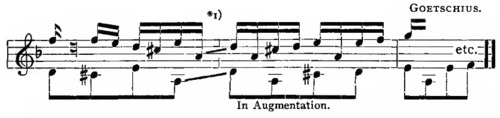

198. Canon in Augmentation. The two parts generally begin together or nearly so, usually in the 8ve; and the Augmentation constantly widens the distance between Leader and Follower, so that it is of course impossible to imitate the entire Leader. Usually, therefore, the second half of the leading voice is a free counterpoint to the portion of the Follower still due; but many devices, such as exchanging the parts, or substituting Diminution after a while, may be resorted to. For example:

Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Canon I; Augmentation and Contrary motion.

199. In Diminution. Here the distance between the parts is constantly decreased, so that the Follower overtakes the Leader after the first time-interval has been exactly doubled. Thereafter the calculation is reversed, and the imitation becomes “Augmentation.” For example:

*1) The parallel octaves at the confluence of the parts are of course inevitable. From here on, the upper part is, practically, the Leader.

EXERCISE 55.

A. Two examples (major and minor) of the 2-voice Canon in Contrary motion.

B. One example, each, of the Canon in Augmentation and Canon in Diminution, (the latter beginning with time-interval of 4, 6, or 8 measures).