CHAPTER IV.

The Development of Thematic Resources. The Various Modes of Imitation.

23. The necessary co-ordination of two associated contrapuntal melodies is due largely, it is true, to contrasting rhythmic formation, whereby mutual independence of melodic effect is achieved. See par. 22a, second clause.

But, besides this independence or individuality, another condition, that of thematic (or melodic) equality, is vitally essential to a proper co-ordination of the parts; and this condition of thematic equality is obtained by the device known as Imitation, — a device peculiarly characteristic of true polyphonic style.

24. Imitation is the highest of the three progressive species of melodic recurrence.

The first grade, (1) simple “Repetition,” is the recurrence of a melodic figure in the same voice, and upon the same scale-steps. This has its natural types in the echo, bird-calls, and other preponderantly physical manifestations.

The second grade, (2) the “Sequence,” is the recurrence of a melodic figure in the same voice, but upon other scale-steps. This, unless purely accidental, implies the exercise of a certain degree of mental power, and therefore enters actively and significantly into the processes of artistic music.

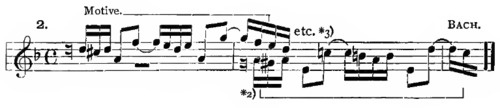

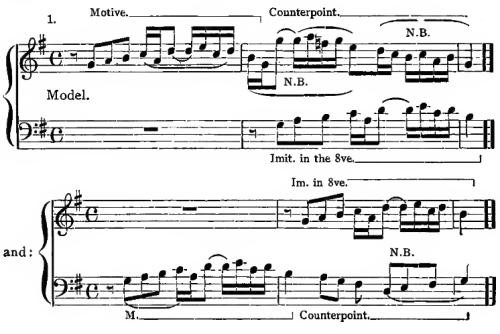

The third grade, (3) “Imitation” proper, is the recurrence of a melodic figure in some other voice, either literally or with modifications. This involves the unanimous co-operation of different individuals, and therefore calls forth still more comprehensive faculties, enters more deeply into the artistic methods of composition, and becomes the most vital factor of Polyphony. For illustration:

[65a: Prelude No. 1 in C major, BWV 846, from WTC Book I, m. 1]

[65b: Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 860, from WTC Book I, m. 1]

[65c: Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 860, from WTC Book I, mm. 51–52]

25. The Imitation of a given melodic figure or motive may occur either above or below the latter; and at any time, — though, as a rule, the temporal relation is regular, i.e., the Imitation appears at the same part of the (next) metric group, so that the arrangement of accented or unaccented units is not disturbed (see Exs. 66, [ex.] 67, etc.).

Further, the Imitation may be effected in a great variety of ways, affecting both the temporal and interval relations. These various modes of Imitation, which constitute an important part of so-called thematic resources, are explained in detail below.

The principal general distinction is that made between Strict (or Rigid) Imitation, and Free Imitation.

Strict Imitation.

26. An Imitation is strict when it adheres exactly to the successive interval-progressions of the initial figure (or motive). This is certain to be the case when it is made upon the same steps of the same scale, i.e., with the selfsame tones, either in the same register (in which case it is called an Imitation in Unison) or, as is far more common, in the next higher or next lower register (called an Imitation in the Octave); possibly in a more distant register, for which, however, no special designation is necessary.

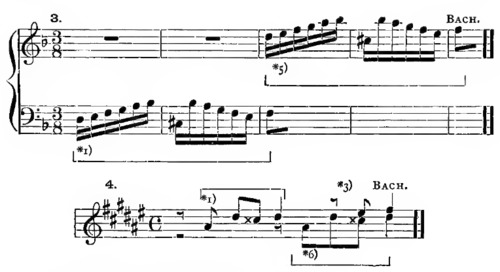

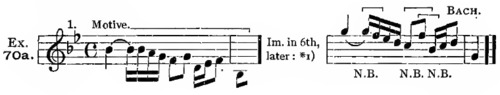

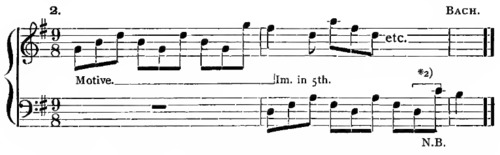

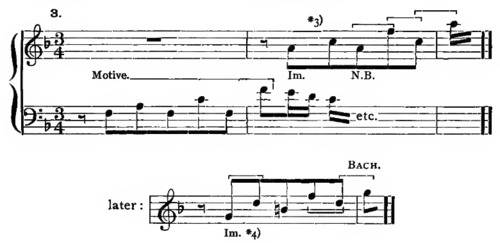

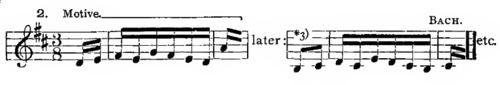

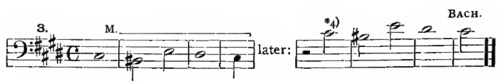

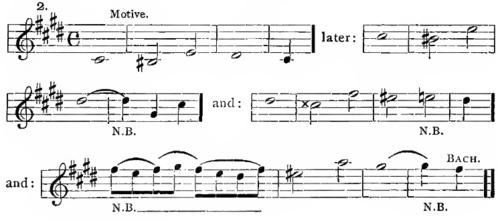

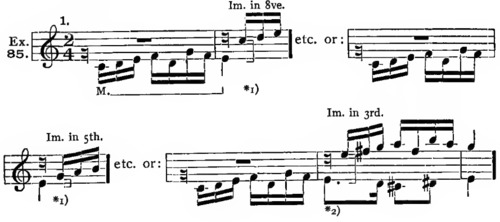

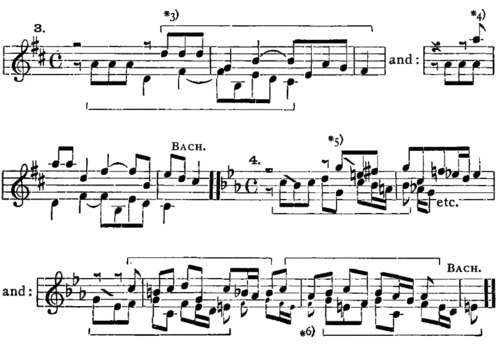

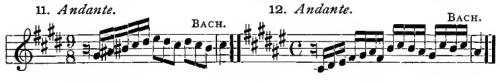

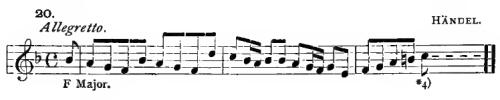

a. The 8ve-Imitation, because of its perfect agreement with, and confirmation of, the motive (par. 38a), is the most natural, simple and frequent, especially for the beginning of a polyphonic section. For illustration:

[66-1: Two-Part Invention no. 13 in A minor, BWV 784, mm. 6–7]

[66-2: Two-Part Invention no. 8 in F major, BWV 779, mm. 1–2]

[66-3: Two-Part Invention no. 4 in D minor, BWV 775, mm. 3–6]

[66-4: Fugue No. 13 in F♯ major, BWV 858, from WTC Book I, mm. 13–14]

*1) The “Motive,” or leading figure.

*2) The “Imitation” of the motive, in the upper octave (or, in the upper part, in the octave).

*3) What takes place here in the leading part during the Imitation, has nothing to do with the latter, and will be considered later (par. 34).

*4) Imitation of the motive in the lower octave.

*5) Imitation of the motive in the double-octave, above.

*6) Imitation in unison (in lower part).

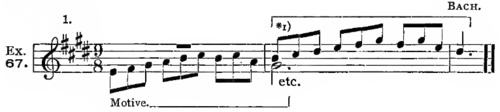

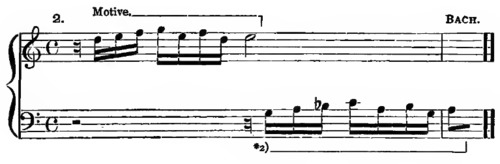

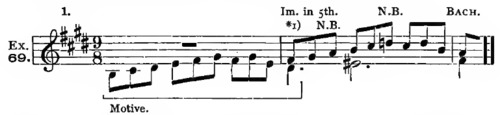

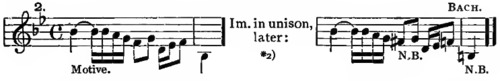

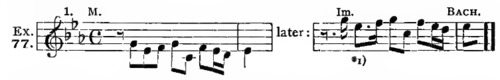

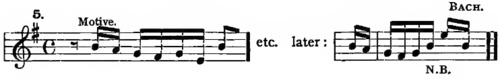

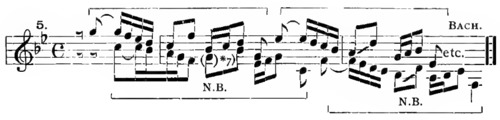

b. It is also possible to imitate a motive upon other, higher or lower, steps of the scale, without altering any of the given intervals (i.e., strictly):

[67-1: Sinfonia No. 6 in E major, BWV 792, mm. 1–2]

[67-2: Sinfonia No. 4 in D minor, BWV 790, mm. 1–2]

*1) Imitation of the motive in the 5th, above; i.e., each tone of the Imitation is the perfect 5th of the corresponding tone of the motive. It is a “strict” Imitation because the successive progressions coincide exactly, in quantity and quality, with those of the motive. This is quickly verified by observing that the Imitation represents the same scale-steps in B major that the motive does in E major. Consequently, the melodic and harmonic conditions have remained unchanged (though a change of key is implied), — and this is the result peculiar to all Strict Imitations.

*2) Imitation of the motive in the 5th, below, — not in the “5th reckoned downward,” but in a “lower part” in the 5th. It must be borne in mind that interval-relations are always determined by counting upward, along the line of the scale, — precisely as the scale-steps are numbered, irrespective of their accidental location above or below a given Tonic. The Imitation in the 5th, of a figure beginning upon d, will always begin upon a, whether placed in a higher or lower part.

*3) The Imitation is strict; but an inflection of the scale, resulting in a modulation from d into a minor, is necessary, to prevent alteration of the original series of interval-progressions.

c. But, as seen already in the second of the above illustrations, the Strict Imitation in any other interval than the octave, is quite likely to call for inflections of the original scale, equivalent to more or less pronounced modulations. Thus:

[Two-Part Invention no. 10 in G major, BWV 781, mm. 16–17]

[Two-Part Invention no. 1 in C major, BWV 772, m. 18]

*1) Imitation above, in the perfect 4th (strict, each tone in the perfect 4th — the key changing from G to C).

*2) Imitation below, in the 4th (strict, — modulation from C to F).

*3) Imitation above, in the minor 7th (strict, — the same scale-steps in f minor as before in g minor).

*4) Imitation above, in the major 2nd (strict,— modulation from C to D).

*5) Imitation below, in the 2nd (strict, — e minor to f♯ minor).

*6) Imitation above, in the minor 3rd (strict).

*7) Imitation below, in the major 6th (strict, — modulation from C to d minor).

Free Imitation.

27. The precision of interval-succession observed in all the above examples of Strict Imitation, is, however, too whimsical and irksome to be insisted upon; and, therefore, such desirable licenses, or intentional modifications, as come under head of Free Imitation, are not only-sanctioned but required, as conducing to greater freedom of manipulation, and to more complete development of the possibilities latent in the adopted thematic material (Motive).

These licenses may affect either the melodic or rhythmic form of the motive to be imitated; they may be either essential or unessential in nature (according to the extent and quality of the changes); or they may even assume complex forms by associating different varieties of modification. The extent to which the licenses of Imitation may be carried, is subject to but one limitation, namely, the ready recognizability of the original motive; that is, all the essential, or striking, characteristics of the motive should be preserved. Upon this unquestionable recognizability of the leading figure (motive), the argument of par. 23 depends.

Unessential Melodic Changes.

28. In Free Imitation with Unessential melodic changes, the modifications may affect

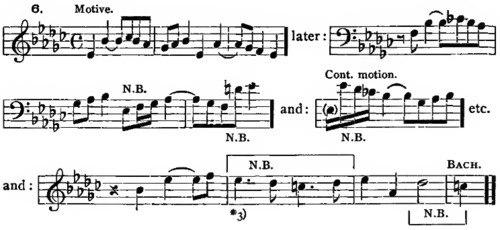

a. The quality of one or more of the original interval-successions.

That is, a perfect interval may be altered to its augmented or diminished form; or a major one to its minor form, or vice versa; etc.

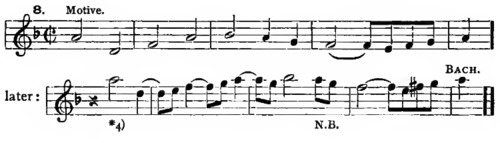

These qualitative changes are illustrated in the following:

[Sinfonia No. 6 in E major, BWV 792, mm. 19–20]

[Sinfonia No. 14 in B♭ major, BWV 800, m. 1, 7]

[Variation 9, mm. 1–2, “Canone alla Terza a 1 Clav.,” from the Goldberg Variations, BWV 988]

[Variation 21, mm. 1–2, “Canone alla Settima,” from the Goldberg Variations, BWV 988]

[Klengel, Canon XVII from Canons and Fugues, Book I, mm. 1–3]

*1) In order to be a “strict” Imitation in the perfect 5th, each and every tone of the motive should be answered in that interval, so that the tones of the Imitation would agree with the f♯ major scale, as those of the motive do with B major. But this is not the case here: the first and second tones (b, c♯) are answered in the perfect 5th (by f♯, g♯); but the next tone, d♯, is answered by a♮ the diminished 5th, hence altered in quality of interval-succession. The same is true of the following g (answered by d♮).

*2) This “later” version does not follow the motive as immediate Imitation of the latter. But “Imitation” in the broader sense means not only Reproduction with special reference to the preceding tones of some other part, but the general Recurrence or reappearance of the motive at different times and in different parts, in the design of the whole.

*3) In order to be a strict Imitation in the major 6th, these tones should conform to the scale of E major (beginning with g♯); or, if an Imitation in the minor 6th, they should represent the E♭ major scale. Instead of either of these, the tones are so chosen as to confirm the original scale (G major). This illustrates the prime advantage, and even necessity, of occasional qualitative changes; while infringing somewhat upon the original melodic and harmonic conditions of the motive (comp. Ex. 67, note *1), they tend toward a far more desirable modulatory unity.

*4) The motive is simply transferred to the next lower (or 7th higher) step of the same scale (g minor); this involves such changes in the quality of the interval-successions as the concession to the prevailing scale demands.

*5) Imitation upon the next higher step of the original scale.

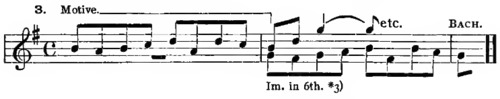

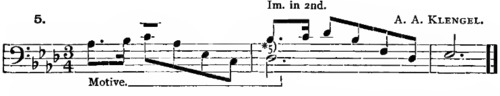

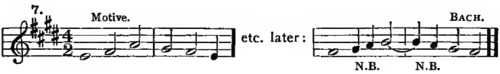

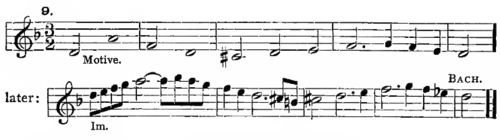

b. Further, the unessential melodic changes may affect the quantity of one or more of the original interval-successions.

That is, the interval of a 3rd may be enlarged to a 4th or 5th, or contracted to a 2nd, etc.

For illustration:

[Sinfonia No. 14 in B♭ major, BWV 800, m. 1, m. 8]

[Two-Part Invention no. 10 in G major, BWV 781, mm. 1–2]

*1) See Ex. 69, note *2).— Compare this version with the motive, and observe what enlargements of the corresponding original interval-successions occur, at the brackets;—the first tone (b♭) is answered in the 6th (g); the next four tones are answered in the 5th; the next in the 7th; and the last four again in the 6th. From this it is evident that the “interval of Imitation” cannot, in such cases, be exactly specified, because of the changes in quantity. It is customary to define the Imitation according to the interval most frequently used, — generally, though not always, that indicated by the very first tone.

*2) Here a contraction from 8ve to 7th occurs. This reveals another of the favorable features of the change in interval-quantity, namely, that it alters the harmonic aspect of the motive. In this case the original motive, which represents a “triad” form, is modified to a “chord of the seventh.”

[Two-Part Invention no. 8 in F major, BWV 779, mm. 1–2, m. 7]

At *3) the triad-form of the motive is changed, both by enlargement and contraction, to the form of a “chord of the sixth.” At *4) it is changed to a chord of the seventh.

c. As important as these alterations of the melodic and harmonic form of the original motive may appear to be, in themselves, the particular object of the unessential melodic changes will be found to consist, chiefly, in facilitating the adjustment of the motive (upon its periodic recurrences) to the prevailing modulatory conditions, or to any immediate or general requirement of the total design.

When the motive is imitated in any other interval than the 8ve, — that is, when it is shifted to other steps of the scale than those which it originally occupied, — the melodic conditions are changed, of course, and possibly seriously disturbed. To counteract this, two things may be done:

(1) A modulation may be made (into any next-related key), changing the scale in such a way that the new location of the motive shall represent correct step-progressions. Or,

(2) The above quantitative melodic changes may be undertaken in the Imitation itself, so that the otherwise faulty successions are removed.

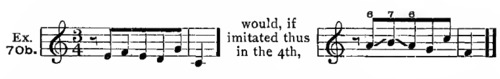

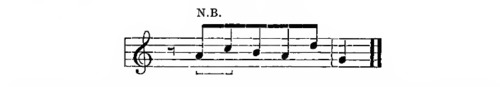

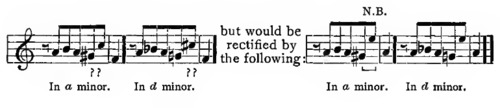

For example, the following motive, in C major:

[would, if imitated thus in the 4th,] assume an awkward and defective form, if retained in C major without change of interval-quantity; but it may be redeemed, either by changing the key:

or by altering the size of the first interval:

or by resorting to both devices; if transferred to a minor or d minor, without further change, the result would again be faulty [but would be rectified by the following]:

Essential Melodic Changes.

29. In free Imitation with Essential melodic changes, the following distinctions of species are made:

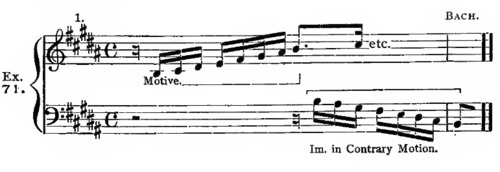

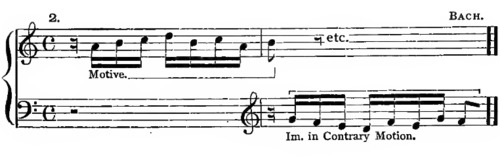

a. Imitation in contrary motion. Here, the direction of each tone-succession of the Motive is reversed in the Imitation; i.e., all ascending progressions are changed to descending ones, and vice versa. As these changes, though radical in their nature, affect each and every tone alike, the result is a legitimate uniform modification; though turned “upside down,” it is the same melodic line, and invariably recognizable as such.

The term “inverted motive” is permissible; but it is judicious to restrict the word “inversion” rigidly to the local relation of two or more parts to each other, as involved in so-called double-counterpoint (see par. 55).

For illustration:

[Prelude No. 23 in B major, BWV 892, from WTC Book II, m. 1]

[Two-Part Invention no. 1 in C major, BWV 772, mm. 8–9]

The size of the interval-progressions may be in “strict” accordance with those of the Motive, but this is by no means necessary, or even desirable. The “interval of Imitation” cannot be defined as in par. 26, obviously, because the melodic lines are not parallel, but contrary; but they appear to revolve, in opposite directions, about a certain mutual axis, or corresponding tone, and the choice of this tone is significant in determining the degree of coincidence, both harmonic and melodic, between the Motive and its Imitation.

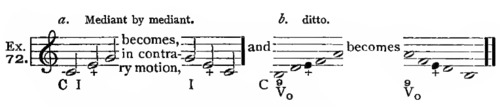

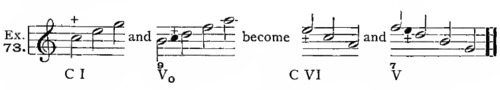

If, for instance, every Mediant (3rd Scale-step) in the Motive is answered by a Mediant in the Imitation, the several tones of the Tonic chord and also of the Incomplete Dominant 9th chord (the most important fundamental harmonies) will reappear, in reverse order. Thus:

The harmonic similarity is therefore complete.

This coincidence may also be defined as tonic note responding to dominant note for that is the natural consequence of Mediant responding to Mediant.

The same is true of the corresponding minor (c minor). And it applies to these tones either in their simple harmonic form, or embellished, — as basis of an ornate melodic motive.

If, further, each Mediant in the Motive be answered by a Tonic note, the result will be:

which constitutes very nearly the same degree of harmonic coincidence as above. Consequently, these two varieties of melodic relation,— Mediant responding to Mediant (= Tonic to Dominant) and Mediant responding to Tonic, — are the best for the Imitation in Contrary motion. These, and other conditions, are illustrated in the following:

[Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 851, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3, 27–28]

[74-2: Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 860, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–4, 20–24]

[74-3: Two-Part Invention no. 1 in C major, BWV 772, mm. 17–18]

[Fugue No. 14 in F♯ minor, BWV 859, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–4; 32–35]

*1) The Mediant (f) in the motive becomes each time again f in the Imitation: i.e., Mediant responds to Mediant; or Tonic (d) responds to Dominant (a), and vice versa.

*2) Mediant responds to Mediant (or Tonic to Dominant) up to the 2nd beat of the fourth measure, when one of the quantitative changes shown in Ex. 70A takes place.

*3) Here, Mediant responds to Tonic. The same is true of Ex. 71, No. 2.

*4) Tonic responds to Tonic. See also Ex. 71, No. 1.

*5) Might just as well have been d♮, but for the desirable modulation.

While such melodic coincidences may, and perhaps should, be adopted as a means of obtaining the first (and best) version of the Imitation in Contrary motion, it must be understood that when the melodic line or figure of the “Contrary motion” has been once thus fixed, it may be shifted about to any steps in its own, or some other, scale—possibly with such unessential changes as are indicated in par. 28. Comp. Ex. 69, Note *2).

b. Retrograde Imitation (cancrizans), in which the motive is reproduced backward. This alteration so seriously endangers the recognizability of the motive, that it may scarcely be regarded as a legitimate or permissible mode of Imitation; and, in truth, its adoption in modern Polyphony is extremely rare. See par. 27, last clause.

[Mozart: Symphony No. 41 in C major, K. 551, IV, mm. 1–4; 227–230 (vla & vc)]

An extraordinary example of Retrograde Imitation may be found in Beethoven’s Pfte. Sonata, op. 106, in B♭ major, last movement. The long and unique Subject at the beginning of the Allegro risoluto reappears in reversed order (i.e., backward) at very nearly its full length, in the first nine measures of the section with the 2♯ signature,— in the lower part; the same form follows immediately in the upper part, and then in the lowermost part. It is characteristic of Bach’s conception of pure Polyphony, that this device does not appear at all in his “Art of Fugue,” a work replete with all the legitimate devices of contrapuntal texture.

Unessential Rhythmic Changes.

30. In Free Imitation with Unessential rhythmic changes, the following licences occur:

a. The value of the final tone of the motive may be either increased or reduced. This utterly harmless modification is illustrated in Ex. 67, No. 1; Ex. 68, No. 2; Ex. 69, No. 1; Ex. 70A, No. 3; and Ex. 74, No. 3, — which see.

b. The value of the first tone of the motive, also, may be increased or decreased (by beginning the Imitation correspondingly earlier or later). Neither of these modifications is purely arbitrary, but will, in the majority of cases, be dictated by the necessity of adjusting the thematic figure, at either of its extremities, to the general design, — especially as concerns the harmony and modulation. For illustration:

[Sinfonia No. 10 in G major, BWV 796, mm. 3–5, 11]

[Two-Part Invention no. 3 in D major, BWV 774, mm. 1, 9–10]

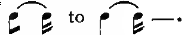

*1) The first tone is lengthened, from

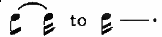

*2) The first tone is reduced, from

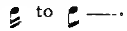

*3) Both the first and second tones are lengthened, from

[Fugue No. 4 in C♯ minor, BWV 849, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–4, 7–10]

*4) The first tone is reduced, and the value of the last tone is also changed. The reasons for these and similar changes are amply apparent in the context of the original.

c. More rarely, the value of certain tones in the course of the motive may be modified, — generally in such a manner that what is added to one beat is subtracted from the neighboring beat, so that the rhythm of the remaining tones, and the effect as a whole, is not disturbed. These changes are largely arbitrary, and are made more for the sake of variety and heightened effect, than from necessity of adjustment. For illustration:

[Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 871, from WTC Book II, m. 1, 8]

[Fugue No. 8 in D♯ minor, BWV 853, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3, 20–22]

[Prelude No. 4 in C♯ minor, BWV 849, from WTC Book I, mm. 8–9, 26–27]

*1) The rhythm of the 2nd beat is altered from  to

to  ; the first and last tones are also modified.

; the first and last tones are also modified.

*2) The value of the 7th and 9th tones is decreased, and, as no equalization takes place, the second half of the motive appears dwarfed. The first tone is lengthened.

Essential Rhythmic Changes.

31. Free Imitation with Essential rhythmic changes involves the following modifications:

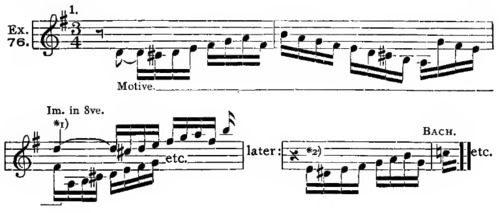

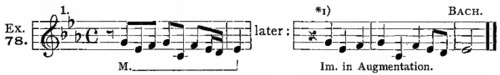

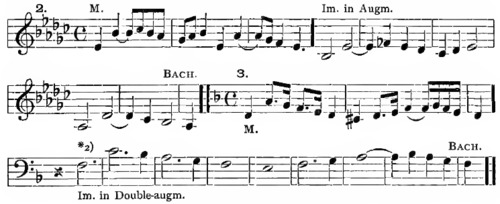

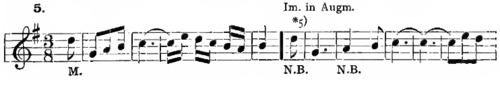

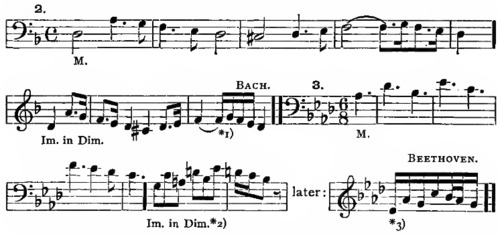

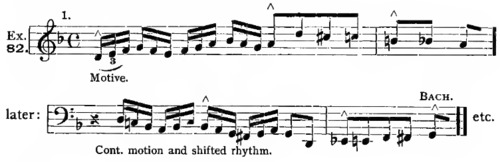

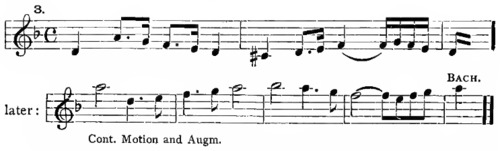

a. Imitation in Augmentation. Here the time-value of each tone and rest is multiplied in uniform ratio. Thus, the length of the motive is usually exactly doubled, although three-fold and even four-fold augmentation sometimes occurs. This applies naturally to motives in duple rhythm; whereas in triple time it is often necessary to resort to uneven proportions of augmentation, in order to preserve the original arrangement of accented and unaccented tones. This change, though essential, does not jeopardize the recognizability of the motive, for it has usually simply the effect of decreasing the tempo without affecting any of the melodic or rhythmic proportions of the original tones. For illustration:

[Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 871, from WTC Book II, m. 1; mm. 14–16]

[78-2: Fugue No. 8 in D♯ minor (here in E♭ minor) BWV 853 from WTC, Book I, m. 1; mm. 62–67]

[78-3: Art of Fugue, Contrapunctus 7, mm. 1–2; mm. 24–29]

[78-4: Beethoven: Piano Sonata no. 31 in A♭ major op. 110, IV: mm. 26–29; mm. 160–168]

*1) The principle of Augmentation operates from the accented units, and therefore affects, in this case, the initial rest also.

*2) The [quarter] rest contracts the value of the first (augmented) tone from [whole] to [half]. It is a four-fold enlargement, — sometimes called double Augmentation.

*3) This example of Augmentation also involves a shift of rhythm, — explained in par. 31.

At *4) the proportions of Augmentation are uneven (three-and four-fold).

*5) Here the proportions of Augmentation are necessarily uneven; otherwise, the triple measure would be transformed into duple.

The version at *6) conforms a little more closely to the prosodic effect of the original motive.

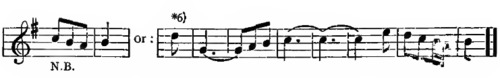

b. Imitation in Diminution. This is exactly the reverse of the above, and has the effect of increasing the tempo without changing the design of the motive. It is hardly feasible in any other than duple measure. For example:

[Fugue No. 9 in E major, BWV 878, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–2, 27]

[179-2: Art of Fugue, Contrapunctus 6, mm. 1–4, 3–5]

[179-3: Beethoven: Piano Sonata no. 31 in A♭ major op. 110, IV (Fuge): mm. 26–29; mm. 156–157, 168]

*1) The rhythm of these four notes is equalized by cancelling the dots.

*2) A reduction to one-third of the original values. The prosodic effect of the motive is totally changed.

*3) A fragment, only, of the motive, in still more extreme Diminution.

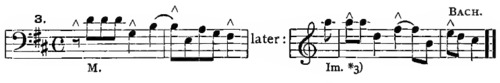

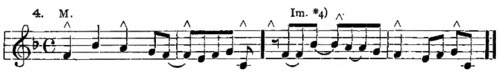

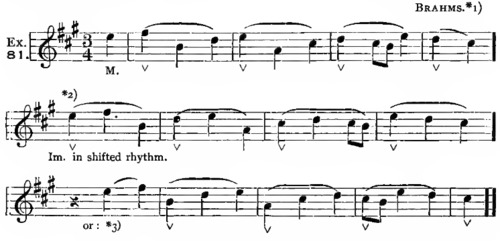

c. Imitation in Shifted rhythm; that is, the reproduction of the motive at a different part of the measure, so that the original arrangement of accented and unaccented tones is more or less completely changed.

In 4-4 measure, a shift of two beats simply produces an exchange of accents, without appreciable change of prosodic effect. This is illustrated in Ex. 66, No. 1 (the motive begins in the 3rd beat, the Imitation in the 1st); Ex. 68, Nos. 2, [no.] 3, [no.] 4, and [no.] 7; Ex. 69, No. 4; Ex. 71, Nos. 1 and [ex. 71, no.] 2.

In 4-4, or any other variety of duple measure, an entirely new arrangement is obtained by shifting the motive one beat, forward or backward; or, as is more rarely the case, by shifting it a fraction of one or more beats, so that the original full beats fall between the pulses, and the Motive assumes a syncopated form. For example:

[80-1: Sinfonia No. 14 in B♭ major, BWV 800, mm. 1, 12–13]

[80-2: Fugue No. 22 in B♭ minor, BWV 867, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3, 68–70]

[Fugue No. 5 in D major, BWV 874, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–2, 27–29]

*1) The Motive, as Imitation, is shifted forward one beat. Observe the change in the location of the accented tones; play each version several times, with very marked accentuations.

*2) In slow tempo, this will appear to be the simple exchange of primary and secondary accents; but the difference in effect is, nevertheless, sufficiently noticeable.

*3) Shifted backward one beat.

*4) Shifted forward one-half beat (syncopated Imitation).

In 3-4, or any other variety of triple measure, the prosodic transformations are still more numerous, because the accented tones may be shifted to either of the two unaccented units, with totally different results. Besides this, syncopated Imitation is also possible, as above. For illustration:

[Brahms, Piano Quartet No.2, Op.26, III, mm. 1–4]

*1) This phrase is borrowed from the pianoforte-quartet in A (3rd movement), merely to illustrate, in a peculiarly effective manner, the two-fold transformation possible in triple measure. At *2) the motive is shifted forward, and at *3) backward, one beat.

32. Complex forms of Imitation, such as Contrary motion, and, at the same time, unessential melodic or rhythmic changes; or simultaneous Contrary motion and Augmentation, Diminution, or Shifted rhythm, and so on, — are possible and not uncommon. But it must be remembered that the more these licences are multiplied, the more likely they are to endanger, or destroy, that recognizability of the original motive designated in par. 27 as the inexorable limit, beyond which it would be inconsistent to pass. For example:

[Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 875, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–2, 17–18]

[Fugue No. 9 in E major, BWV 878, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–2, 35]

[Art of Fugue, Contrapunctus 7, mm. 1–2; 2–6]

*1) Imitation in Contrary motion and Diminution; the value of the first tone abbreviated. — A few other cases of slight complication are shown in Ex. 74, No. 2: Ex. 78, No. 3; and Ex. 79, No. 2.

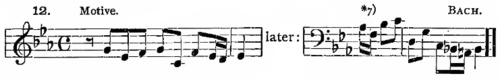

33. Finally, more exceptional forms of modified Imitation are occasionally encountered in the polyphony of Bach and others, consisting, (1) in the addition of intermediate embellishing tones; (2) in the contrary motion of some single interval; (3) the transposition of a portion of the motive to a higher or lower octave; and (4) the partial application of certain essential modifications (i.e., to certain figures, only, of the motive). Such miscellaneous changes are most justifiable when made for the sake of adjusting the Imitation to some legitimate and obvious thematic purpose; or to facilitate obstinate and awkward, but manifestly necessary, contrapuntal movements. (Comp. par 12c.) And, as usual, they should not infringe upon the recognizability of the original motive. For illustration:

[Sinfonia No. 11 in G minor, BWV 797, 1–3]

[Fugue No. 4 in C♯ minor, BWV 849, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–4, 59–62]

[Fugue No. 11 in F major, BWV 856, from WTC Book I, 1–3, 65–67]

[Two-Part Invention no. 9 in F minor, BWV 780, mm. 1–3, 9–11]

[Two-Part Invention no. 7 in E minor, BWV 778, m. 1, 15–16]

[Fugue No. 8 in D♯ minor, BWV 853, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3, 77–79, 39, 24–27]

[Fugue No. 9 in E major, BWV 878, from WTC Book II, 1–2, 23–24]

[Art of Fugue, Contrapunctus 3, mm. 5–9; mm. 23–27]

[Art of Fugue, Contrapunctus 12, mm. 1–5; mm. 21–25]

[Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903, mm. 1–8, 76–83, 107–113]

*1) Comp. par. 4a, 1 (Ex. 9A).

*2) These last tones are transferred to the lower octave, evidently to avoid carrying the part too high.

*3) A curious example of partial augmentation.

*4) The motive is shifted one beat forward, and embellished, during three measures.

*5) This final fragment is transferred to another part.

*6) The motive is shifted backward one beat, and the 6th tone is altered, from the expected g♯ to d♯. Compare No. 5, of this Example.

*7) This well-nigh unrecognizable Imitation is complicated by change of register at single tones.

The Contrapuntal Associate.

34. After the leading part has terminated its Motive, and the Imitation of the latter is annunciated in the other part, the leading part does not discontinue its movement, or even pause briefly, but carries its melodic line along, apparently independent of the Imitation. This projection of the motive-melody must, however, constitute a harmonious contrapuntal associate of the Imitation, and therefore its conduct must be defined according to the rules of two-part polyphony, detailed in Chapter II. It is usually called the “Counter-motive,” or, briefly, the “Counterpoint.”

35. To the general details of contrapuntal association given in the second chapter, the following special rules must be added:

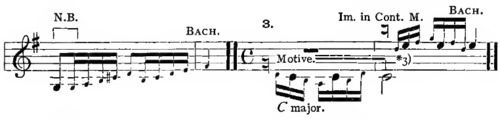

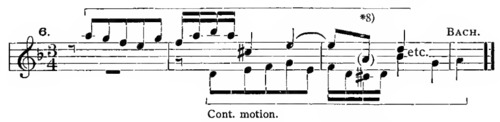

a. The “Counterpoint” must be a perfectly natural continuation of the Motive-melody which precedes it, — as if the imitatory appearance of the other part were rather accidental than intentional, and did not concern the progressive movement of the leading part.

This rule is of the utmost moment in genuine polyphonic texture. For illustration:

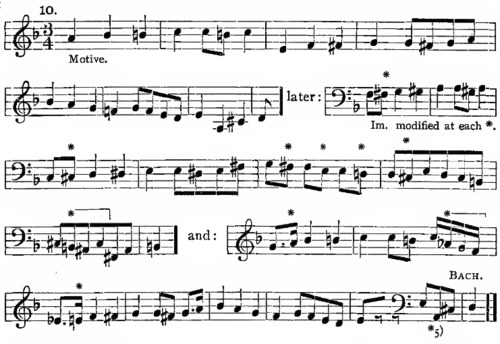

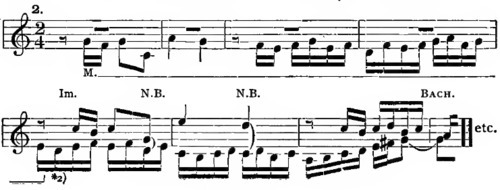

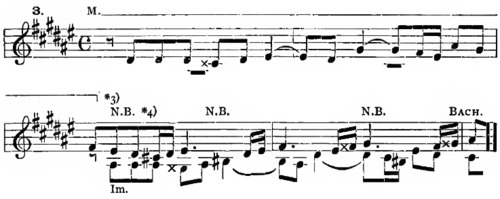

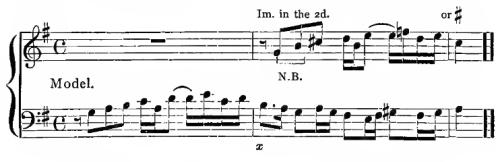

*1) The leading part runs on, apparently regardless of the Imitation (observe the collision at N. B.), in sequential projection of its final member. The importance of the Sequence is here again vindicated; by no other means can melodic evolution be more easily and naturally effected than by the Sequence. See par. 17c. As to the points marked N. B., see par. 17b and 13i.

*2) Here also, the “Counterpoint” is a nearly sequential continuation of the motive itself.

*3) The Counterpoint is all derived, somewhat disguised, from the motive.

*4) See Ex. 45, No. 2.

See also, Bach, Well-tempered Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 5, meas. 1–3; Fugue 9, meas. 1–3; 16, meas. 1–4; Vol. II, Fugue 5, meas. 1–4; 11, meas. 1–8; 12, meas. 1–8.

b. The beginning of the Imitation must be properly adjusted (as regards harmony and modulation) to the termination of the motive. This will influence the choice of the interval of Imitation (par. 26a, [26]b, [26]c); may induce the employment of the unessential rhythmic changes noted in par. 30b and will possibly necessitate the unessential melodic changes given in par. 28a and [28]b, at the beginning of the Imitation.

For example:

*1) The adjustment of the beginning of the Imitation to the termination of the motive is perfect, both as concerns interval and chord, in each of these cases. This is to be expected, when either the Imitation in the 8ve or 5th is chosen; i.e., these intervals are “safe.”

*2) Imitation in the 3rd. It is adjusted well at the very beginning, but leads to a somewhat hasty and undesirable modulation.

*3) Imitation in the 7th. This is good, because the chord-connection (harmonic adjustment) is complete.

*4) Imitation in the 2nd. Like the preceding case.

*5) The size of the first interval is in one case extended, in the other contracted.

*6) The objectionable interval at the outset is softened by shortening the first tone.

*7) Improved by lengthening first tone. See also Ex. 76, No. 1; Ex. 77, No. 3.

c. It suffices, as a rule, to provide thus for harmonic agreement at and during the first beat or two of the Imitation. The subsequent beats may easily be so manipulated, — either by unessential modification of the Imitation itself (par. 28a, [28]b), or by consistent and careful conduct of the “Counterpoint,” — as to achieve good harmonic conditions.

The Imitation once correctly launched, the succeeding movements of the contrapuntal associate are determined, as already stated, by the principles of two-part polyphony, but with more particular regard of the primary rule given at a above (par. 35).

Examine the methods of adjusting the beginning of the Imitation to the termination of the motive, in Exs. 66, [ex.] 67, [ex.] 68, [ex.] 69, [ex.] 70A, [ex.] 71; 74, No. 3; 83, No. 1.

The Stretto.

36. The Imitation is said to be in “stretto” when it overlaps a portion of the motive; i.e., when the Imitation sets in before the motive is finished.

The section of the motive thus covered by a section of the Imitation is, consequently, at the same time the contrapuntal associate of the latter; and, therefore, the practicability of the Stretto is conditional upon reasonable contrapuntal agreement between these sections. This depends

(1) upon the choice of Strict or Free Imitation (pars. 26, [par.] 27); if Strict, — if no concessions are to be made, — then but few Stretti will be found feasible, though the rules of par. 12c and par. 17b (which see) provide an excuse, at least, for some harshness of effect; if Free, then the judicious application of the unessential licences of par. 28a, [28]b, will make almost any Stretto possible. It depends, further,

(2) upon the length of the overlapping section.

The earlier the Imitation appears, the longer will the overlapping section be, and, consequently, the more protracted the risk of disagreement. Hence, fewer Stretti will be practicable after only one or two beats (i.e., from the beginning of the motive) than after a longer period, nearer the end of the motive. But, here again, slight alterations in interval-quantity will facilitate even such extreme Stretto-Imitations.

Specimens of incipient forms of the Stretto are seen in Ex. 66, No. 3, and Ex. 67, No. 1, where the Imitation begins simultaneously with the final unit of the motive; this brief interlinking of the two parts (not strictly “overlapping”) involves no more than the rule of par. 35b. See also Ex. 68, Nos. 1, [68]-5, [68]-6; Ex. 69, Nos. 1, [69]-3, [69]-5.

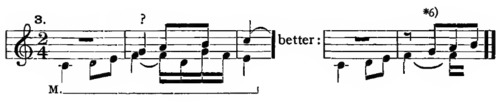

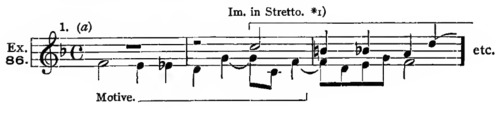

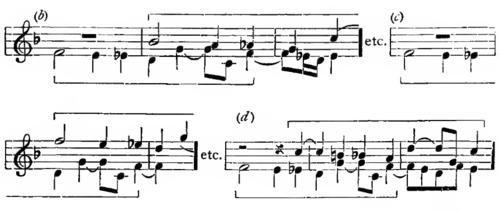

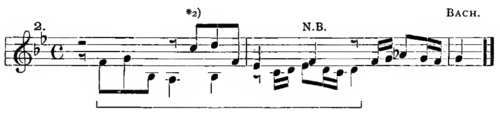

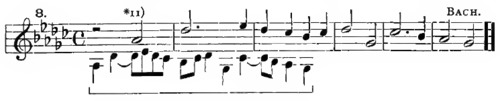

Illustrations of the genuine Stretto: —

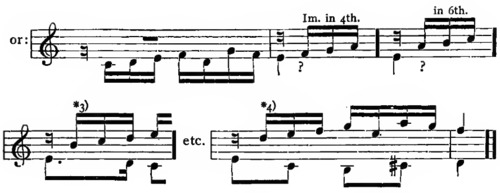

*1) In defining a Stretto-Imitation, both the melodic and rhythmic intervals are specified: At (a) it is a Stretto “in the 5th, after six beats;” at (b) in the 4th, after one measure; at (c) in the octave, after one measure; at (d) in the 5th, after three beats; at (e) in the 5th, after two beats; and at (f) in the 6th, after one beat. This motive is peculiarly adapted for the Stretto, as it yields all of these grades without a single alteration in interval-quantity.

*2) After two beats, in the 5th. The collision at N. B. is justified by the principle of par. 12c.

*3) After two beats, in the 4th, Strict.

*4) After one beat, in the octave, Strict.

*5) The quantity of the first interval-progression is changed, to facilitate the Stretto.

*6) The same Stretto as in the preceding measure, but with inverted parts.

*7) The Stretto begins in the 4th, after one-half beat; at this point the tone g is inserted, and the Stretto then continues, at the distance of a whole beat. In the next measure, a change in interval-quantity is made, for an evident reason.

*8) Comp. Ex. 10 and context. This is a Stretto “in Contrary motion.”

*9), *10) An extraordinary example of the Stretto: first in the 7th, after one beat; and then in Contrary motion, after one beat, without changing a single interval, during almost the entire length of the unusually long motive. The student’s experiments with his own motives will contribute most convincingly to his admiration of such contrapuntal feats as this.

*11) Stretto in Augmentation. See also Ex. 85, No. 3. See further, Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 1, meas. 7–8, 17–18 (Tenor and Bass); 6, meas. 21–25; 20, meas. 27–31 (Soprano and Tenor), meas. 64–68 (Bass and Tenor). Vol. II, Fugue 2, meas. 14–15 (in Augmentation); 3, meas. 1–3 (cont. motion); 6, meas. 14–15.

EXERCISE 7.

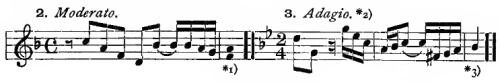

A. Each of the following given Motives is to be extended by an Imitation (in the specified interval) and a Contrapuntal associate, as shown in the subjoined model.

As a rule, two staves are to be used, and care should be taken to prevent the two parts from diverging too widely from each other, — very rarely more than two octaves apart, usually much less.

Each Motive is to occupy first the upper part, followed by its Imitation in the lower; then the lower part, with Imitation in the upper; and each time a different Counterpoint must be devised.

Review the summaries, par. 13 and par. 21; also par. 22a, par. 35a, [35]b, [35]c.

This exercise is to be limited to par. 26a, — Strict Imitation in the Octave.

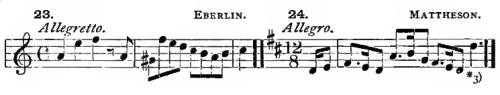

The student is expected to manipulate this (No. 1) again, in his own way. Then Exercise 6B (page 58), Nos. 3, 4, 5, 2, 6, 7, 8. Then the following: —

*1) Final tone optional, both as regards choice and duration.

*2) The tempo-indications must not be overlooked; they may affect the rhythm of the Counterpoint.

*3) Duration optional; and the same in every succeeding case.

*4) The Motive ceases with this tone, whose value, and the continuation of the part, up to the entrance of the Imitation, are optional.

*5) The tie is optional.

B. A number of these motives (as specified below) to be manipulated according to par. 26b,— Strict Imitation in the 5th.

Each motive, as before, imitated both above and below. Especial attention to par. 35b ([par.] 35c) will be necessary.

Motives adapted to this exercise:

Exercise 6B, Nos. 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8;

Exercise 7A, Nos. 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, 18, 20, 21, 23, 25.

EXERCISE 8.

A. Manipulate the motives specified below, in various other intervals of Imitation (in the 3rd, 4th, 6th, possibly 2nd or 7th); all in Free Imitation, according to par. 28a and [28]b.

The practicable intervals of Imitation will be determined in keeping with par. 35b; and it must be understood that the unessential melodic changes there referred to are not arbitrary, but should be resorted to only as an expedient, when the Strict Imitation baffles harmonious adjustment, — or in order to secure better modulation. Review Ex. 69, Note *3), and Ex. 70A, Note *2). And observe particularly par. 28c.

For this purpose, employ the following Motives:

Exercise 6B, Nos. 1, 5;

Exercise 7A, Nos. 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 16, 18, 20, 21, 25.

B. Manipulate a few motives (Exercise 7A, Nos. 1, 7, 9, 11, 26) with the licences of par. 30b, and, occasionally, [30]c, — Imitation with unessential rhythmic changes. Any interval of Imitation may be used (especially 8ve, 5th or 3rd).

EXERCISE 9.

A. Manipulate the following motives according to par. 29a (Contrary motion), in various methods of response (Exs. 72, [Ex.] 73; Ex. 74, Note *4):

Exercise 6B, Nos. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8;

Exercise 7A, Nos. 3, 6, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 22, 23, 26.

B. Manipulate the motives specified below, according to par. 31a (Augmentation). Any interval of Imitation may be used, preferably the 8ve, 5th or 3rd.

*1) It is necessary, in the contrapuntal associate of an Augmentation (because of its length and persistently heavy rhythm), to check the rhythmic current from time to time, — especially at the outset, and at any heavy accent.

For this purpose, employ Exercise 6B, Nos. 2, 3, 6;

Exercise 7A, Nos. 2, 12, 16, 4, 5, 11, 17.

C. Manipulate the following, according to par. 31b (Diminution):

Exercise 6B, Nos. 3, 7;

Exercise 7A, Nos. 4, 19, 26 (10).

D. Manipulate the motives specified below according to par. 31c (Shifted rhythm):

*1) The Imitation is to be shifted forward in each case, — generally one beat, possibly a little more or less. The vacant space that consequently intervenes between the end of the motive and the beginning of the Imitation, must be very carefully filled out, with close attention to the rule of par. 35a, i.e., with strictly analogous material. The interval of Imitation will be almost entirely optional, depending somewhat upon the current of the “intervening tones.”

*2) In every case, both parts must be thus carried on, to the next accented beat, — with strictly analogous material. For this purpose employ

Exercise 6B, Nos. 4, 5;

Exercise 7A, Nos. 3, 7, 10, 12, 18, 22. 24.

EXERCISE 10.

Manipulate a number of motives in Stretto-imitations, according to par. 36.

This work is almost purely experimental; the possibility of obtaining one or more acceptable stretti is to be tested patiently, in each of the seven different intervals of Imitation and at different rhythmical distances. The Imitation will, of course, always be shifted backward, and tested at each succeeding beat of gradually increasing proximity to the beginning of the motive. The Stretto-imitations in parallel motion (Ex. 86, No. 1), and in Contrary motion (Ex. 86, No. 6), are both to be tested; occasionally that in Augmentation also (Ex. 86, No. 8). Unessential melodic changes (in quantity of interval) may be admitted, to a reasonable extent.

For this purpose use any motives of Exercise 6B, Nos. 2–8, or of Exercise 7A. Also a few of the original motives invented in Exercise 1B.