CHAPTER II.

Condition 2: “Harmonious Union.” The Association of Two Parts (Voices).

14. The simultaneous conduct of two parts must, naturally, yield a harmonious result; not necessarily wholly, but preponderantly so. The consonant intervals must, therefore, dominate all Essential tones, while the equally desirable and necessary dissonant intermixtures must be limited to the Unessential tones.

The fundamental distinction between Essential and Unessential tones is partly a question of harmony, but more largely (at least in the present connection) one of rhythm, or, rhythmic prominence. Hence, the Essential tones are those which represent and obviously govern an entire metric unit of moderate duration, that is, the full beats in somewhat rapid tempo, and the half-beats in ordinary or deliberate tempo, — possibly the quarter-beats in decidedly slow tempo. The essential tones, in order thus to govern their beats or half-beats, will usually appear at the beginning, or upon an accented fraction, of the same; but not necessarily, as the harmonic quality of the tones (their relation to the momentary chord) is decisive in all doubtful cases.

The Unessential tones are those whose relation to the chord, or the beat, render them manifestly secondary to the essential tones.

Rules for Exclusively Essential Tones.

15. The consonant, or at least harmonious, intervals which are to govern the association of Essential tones, are of three grades: Primary consonances, secondary consonances, and mild dissonances.

a. The primary consonances are:

- The 3rds, major and minor; and

- the 6ths, major and minor.

The quality (major or minor) depends upon the momentary key; and the choice between 3rd and 6th is dictated by the harmonic demands or preference. They are not affected by the enlargement (through an octave of double-octave separation) to 10th, 13th, etc.

These intervals are invariably permissible, at any point, during notes of any reasonable time-value, in practically any order and connection.

An unbroken succession of 3rds (or of 6ths), while inevitably harmonious, and therefore desirable in moderation, nevertheless militates against the necessary independence of the two parts, and should, for that reason, not be protracted beyond 3 or 4 (5) at a time, as a rule.

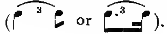

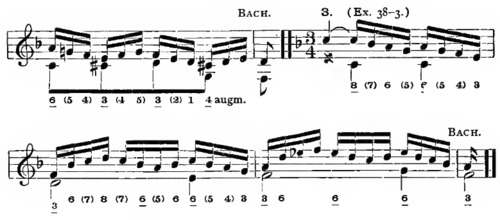

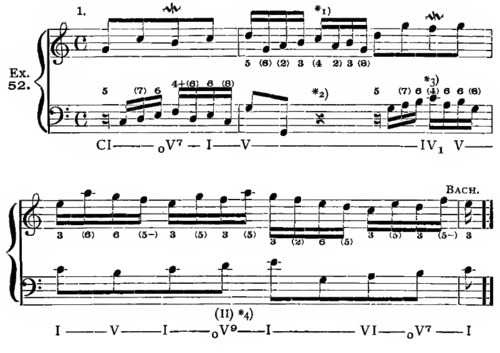

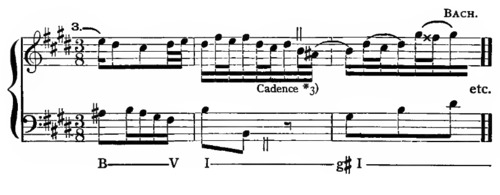

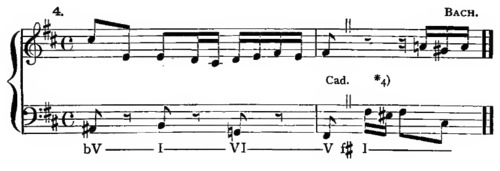

For illustration (adapted from Bach, with omission of the unessential tones contained in the original):

[38-1: Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 860, from WTC Book I, mm. 5—6]

[38-2: Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 875, from WTC Book II, m. 4–5]

[Gottes Sohn ist kommen (fughetta), BWV 703, mm. 4–7]

The complete form of these illustrations is given in Ex. 44, Nos. 1, 44-2, 44-3.

b. The secondary consonances are:

- The perfect 8ve, or unison; and those

- perfect 5ths which represent strong triads (those of the Tonic and Dominant).

The octave is useful, and quite common; it may represent the duplication of any scale-step excepting the Leading-tone (step 7), but is best as Tonic, Dominant, or Subdominant; if it occurs at the weaker steps (2nd, 3rd or 6th) its effect must be carefully tested. The perfect 5th is rare, and always requires to be tested.

Neither of these intervals can occur in succession (8–8, or 5–5), nor should they be interchanged (8–5, or 5–8), as a rule, when the tones are Essential.

Neither of them should be approached in parallel direction, when the upper part makes a wide leap, — always excepting during chord-repetition. A wide leap in either direction, in connection with the perfect 5th, is objectionable, especially in the upper part.

For illustration:

See also Ex. 40, B; Ex. 44, Nos. 4, 44-5.

c. The mildly dissonant intervals, permitted to dominate occasional Essential tones, are:

| The diminished 5th; | } In V7— |

| the augmented 4th; | |

| the diminished 7th; | } In V9 Incomplete (Dim. 7th chord)— |

| the augmented 2nd; |

and those minor 7ths and major 2nds which represent good chords of the seventh.

The diminished and augmented intervals are by no means infrequent; but the major 7ths are very rare.

None of these intervals can be used in succession, nor, as a rule, interchanged; i. e., they should occur only in connection with the primary consonances (3 or 6), or, more cautiously, with secondary ones (par. 15b).

They must not be introduced abruptly; the wide leap, in either part, toward any of them should be avoided, — excepting during chord-repetition. If a chord-7th or 9th is involved, it must be properly resolved.

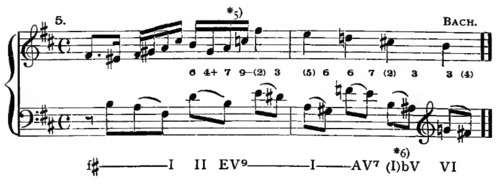

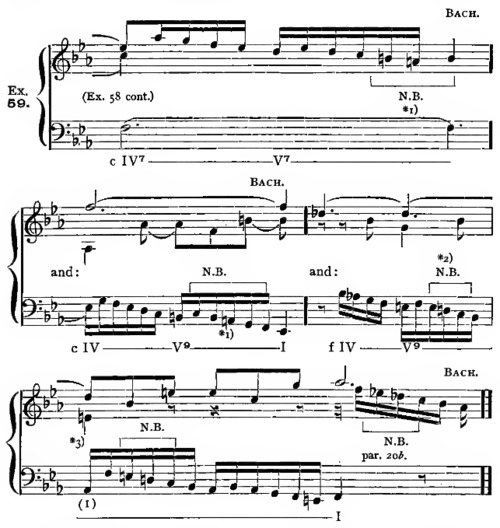

For illustration:

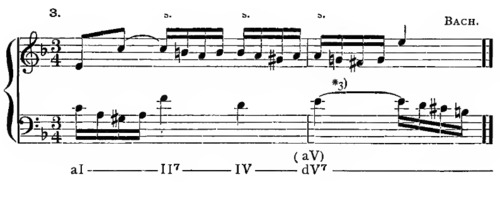

[Sinfonia No. 13 in A minor, BWV 799, mm. 1–4]

See also Ex. 44, No. 2, and [ex. 44] Nos. 6–9.

d. Additional general rules:

It is mainly important that each part, alone by itself, should constitute a perfect, well-designed melody; therefore the rules of melodic conduct, given in Chap. I., must be strictly regarded.

And the use of the Sequence, or any other factor which imparts design and purpose to the melody, is of great importance. See par. 17c; and par. 21b.

Further, a good harmonic result must also be achieved, and for that reason the fundamental principles of chord-succession (detailed in par. 18, to which reference should be made) must be respected. Wide leaps, particularly, are to be tested chiefly with reference to these principles.

It is very difficult to justify a wide leap in both parts at the same time, excepting during chord-repetitions.

The two parts should be led, generally, in opposite directions, though by no means necessarily. One part may, at almost any time, remain upon the same tone (reiteration, par. 8) while the other part progresses. See par. 17f.

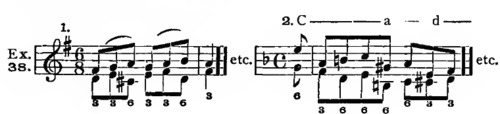

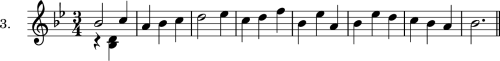

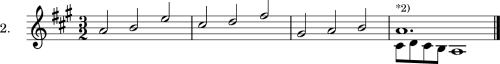

EXERCISE 2.

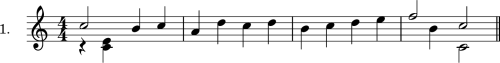

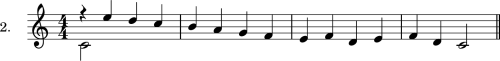

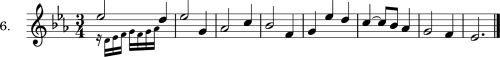

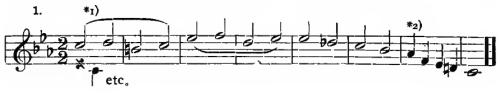

To each of the following given melodies a second part is to be added, according to the rules of par. 15. The two parts are to be essentially similar in rhythm, i.e., a tone in the added part for each tone of the given part; with an occasional exception, as indicated. Every tone, throughout, is to be regarded as essential.

No modulations are to be made.

Each melody is to be manipulated twice; first as upper part, where it is written, and then, transferred to a lower octave, as lower part. The respective added parts must differ from each other.

One staff, or two staves, may be used; if two, the customary G-clef and F-clef. (Should the student chance to be familiar with any of the C-clefs, he may use them also; if not, their use should be deferred. It is unwise to add to the already sufficiently formidable difficulties of the polyphonic style, the difficulty of learning these unfamiliar clefs. After the former have been fully mastered, the student can quickly learn as much about the C-clefs as their comparatively limited uses in modern composition— Instrumentation — call for.)

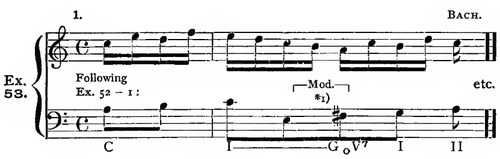

*1) The two parts need not begin together; if the given melody begins on the accent, the added part may rest one beat; and vice versa, as indicated in most of the melodies.

*2) Longer tones in the given part may be accompanied by two tones (even beats) in the added part; and, occasionally, two tones of the given part by one in the added part.

*3) Close upon the Tonic-octave, or unison.

*4) Do not neglect par. 15c.

Unessential Tones.

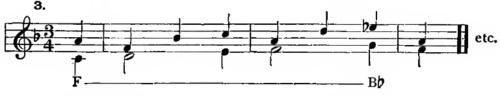

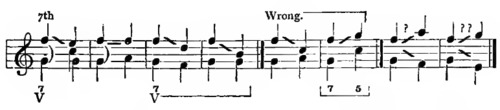

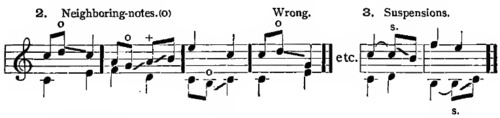

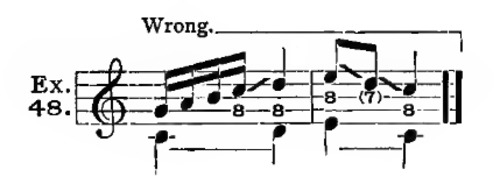

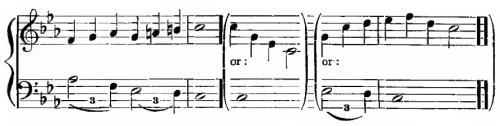

16. The unessential tones may constitute any interval, harmonious or dissonant. But every exceptional interval (not enumerated in the preceding paragraph) must appear as obvious modification of an unobjectionable one, — as transient (passing) note, neighboring-note, or suspension; and must be employed in such a manner as to confirm the distinction between unessential and essential tones. That is, the objectionable interval must be followed immediately, or very soon, by one or another of the perfectly good intervals; thus, 4–3, or 4–6, or 4–5–6; possibly 4–2–6, or 4–2–3; but not 4–2–5–7, or any similar succession. For example:

Concisely stated: some good interval (par. 15) must “govern” the ordinary beat, or half-beat, of moderate duration (par. 14, last clauses). If, for any reason, an exceptional interval governs the beat, the effect will be poor. No reasonable interval-association is impossible, but all exceptional intervals must be palpably unessential, and less prominent than the good ones. The operation of this principle may be tested in the examples which follow, — or in any models of good counterpoint in standard literature.

Further, of the two tones which form an objectionable interval, that one which is obviously non-harmonic (foreign to the chord) should generally enter without leap, though this is not strictly necessary (Exs. 12, [ex.] 32); but it must progress conjunctly (stepwise); excepting the two leaps of a 3rd shown in Ex. 9a (“double-appoggiatura”) and Ex. 9b (unresolved upper neighboring-note); and the “ornamental resolutions” of the suspension, Exs. 10, [ex.] 11.

[ed. note: The figure he marks as “wrong” here in Ex. 42-2 is typically called an “escape tone” or an “incomplete neighbor” tone, and is not considered incorrect now.]

But an unessential tone that might be regarded as harmonic, as a part of the momentary chord, may leap along that chord-line without objection; or may make any reasonable leap even during a change of chord.

Review par. 3a, and par. 4a and [par.] 4b.

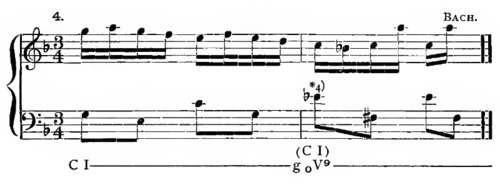

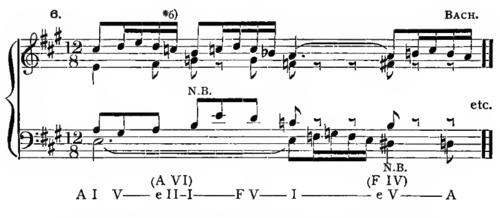

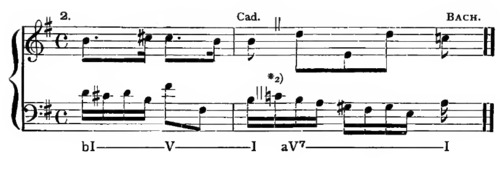

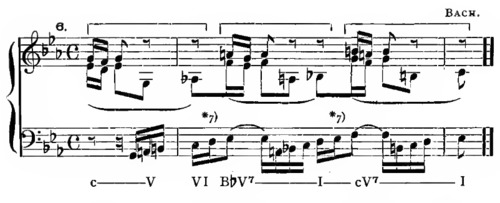

For general illustration (unessential tones in parenthesis):

[44-1: Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 860, from WTC Book I, mm. 5–6]

[44-2: Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 875, from WTC Book II, m. 4–5]

[44-3: Gottes Sohn ist kommen (fughetta), BWV 703, mm. 4–7]

[Sinfonia No. 1 in C major, BWV 787, m. 1]

[Sinfonia No. 10 in G major, BWV 796, m. 1–3]

[Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 875, from WTC Book II, m. 3–5]

[Fugue No. 4 in C♯ minor, BWV 849, from WTC Book I, m. 4–7]

[44-8: Fugue No. 5 in D major, BWV 850, from WTC Book I, m. 3–4]

[44-9: Fugue No. 13 in F♯ major, BWV 882 from WTC Book II, mm. 4–5]

[44-11: Fugue No. 8 in D♯ minor (here in E♭ minor) BWV 853 from WTC, Book I, mm. 3–7]

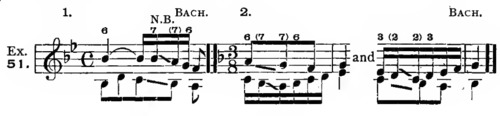

17a. The interval most to be shunned, between two essential (or even semi-essential) tones, is the perfect 4th. It is tolerated, as a rule, only between strictly unessential, and brief, tones.

[Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 851, from WTC Book I, mm. 3–4]

[Fugue No. 8 in D♯ minor, BWV 877 from WTC, Book II, mm. 3–4]

*1) These 4ths, though occupying the accented fractions, are all distinctly unessential.

*2) Here the perfect 4th appears, each time, to govern the beat; but relief (apparently sufficient) is afforded by the consonant interval which accompanies it.

[Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 847, from WTC Book I, mm. 3–4]

*3) The perfect 4th is best justified by constituting a brief tonic-6-4 chord (I2). This is obviously the case here, and at the first 4th in No. 2.

b. Each part must progress in a strictly correct melodious manner (see par. 15d). In perfectly good 2-part polyphony it must be entirely feasible to dissociate the parts and obtain a perfectly good and intelligible melodic result in each alone. So important is this principle, that it sometimes overpowers the otherwise rigorous rules of part-association (detailed in par. 15, 16, etc.). That is to say, if each one of two associated parts pursues a definite and obviously justifiable melodic purpose, they may be conducted with a certain degree of indifference to their contrapuntal details. In the conscious fulfillment of a broader melodic aim, the mind of the hearer may waive the demands of euphony to a certain (limited) extent. (Compare par. 13i.) For example:

[Sinfonia No. 6 in E major, BWV 792, mm. 35–36]

The lower of these two parts has the original Motive (par. 38a); the upper one has, simultaneously, the same Motive in “contrary motion” (par. 29a); — each, therefore, moves according to manifest “thematic authority.”

c. For this very reason, it is eminently desirable that each part (but especially the more rapid part, in protracted uniform rhythm) should exhibit well-defined and regular formation, i.e., should be compounded of more or less lengthy and regularly recurring symmetrical figures, that impart recognizable design to the tone-succession, and prevent it from being a shapeless, rambling, unintelligible, and apparently aimless melodic line.

This emphasizes the importance of the Sequence, without which truly good and intelligible polyphony can scarcely be imagined. But it refers also to all other means by which the evidence of clear form and broader melodic design may be established, and which are quite as necessary as the sequence, — especially at those places where the sequence itself threatens to become tiresome from overuse. The beginner should never employ, at a time, more than three (four?) sequences of a figure (unless the figure be a very brief one). For example:

[Two-Part Invention No. 5 in E♭ major, BWV 776, mm. 3–5]

The succession of figures in the lower part forms a thoroughly intelligible and coherent melodic line; but the groups differ from exact Sequence just sufficiently to avoid monotony. See also Exs. 88, [ex.] 92.

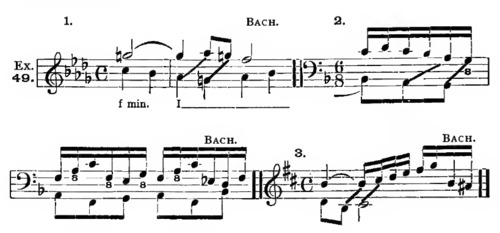

d. As stated in par. 15b and [par.] 15c, it is a part of the limitation of the secondary intervals, that they can only appear singly, — not in succession. Thus, perfect octaves cannot appear in immediate succession under any circumstances; and even when separated by one tone, they are quite as objectionable as immediate octaves, if the intermediate tone is distinctly unessential:

But an “oblique” succession of perfect octaves is generally permissible, if one of the tones of the octave itself is obviously unessential; or better, if it is evident that the two parts maintain their respective melodic independence:

[49-1: Fugue No. 22 in B♭ minor, BWV 867, from WTC Book I, mm. 4–5]

[49-2: Pastorale in F major, BWV 590, IV (mm. 28–29)]

[49-3: Fugue No. 24 in B minor, BWV 869, from WTC Book I, m. 6]

A succession of perfect 5ths is not permitted between essential tones, unless one semi-essential tone, or at least two unessential tones, intervene. When each 5th embraces an unessential tone, or when one of the tones of the second 5th alone is plainly unessential, the succession is not objectionable. Thus:

[50a-3: Two-Part Invention No. 1 in C major, BWV 772, m. 3]

A wide leap to or from a tone that is obviously the Fifth of the momentary chord, must be made with caution. It is generally bad when the chord-fifth forms the interval of a perfect 5th with the lower part (and is taken by wide leap, — especially parallel with the other part). But is harmless:

- During chord-repetition; and

- When the chord is so inverted that the interval of a perfect 5th disappears:

[Two-Part Invention No. 8 in F major, BWV 779, mm. 1–2]

e. The direct succession of any other secondary intervals (i.e., parallel 7ths, 2nds, 4ths, etc.) is permissible only when at least one of the tones involved is distinctly unessential, and very brief. Thus:

* Par. 4a, (1).

f. Partly because of the risk of such disagreeable successions as those involved by parallel movement of the two parts; and partly because such parallel conduct deprives both parts of a certain degree of their respective melodic individuality; it appears desirable to lead the parts in contrary directions, as a very general, though by no means binding, rule. Illustrations of wholly or largely opposite motion (at the points where both parts move) are found in Ex. 42-1; Ex. 44-2; 44-4; 44-6; Ex. 46; — of almost totally parallel motion, in Ex. 44-3; — of largely parallel motion, in Ex. 38-2; 44-7.

For illustrations of unusually protracted parallel motion, see Bach, 2-voice Invention, No. 8, meas. 5, 6; 2-voice Invention, No. 14, meas. 14–16. See, also, 2-voice Invention, No. 9, meas. 1, 2, 4 (contrary), meas. 3 (parallel).

Harmonic Influence.

18. Strict observance of the above detailed rules must lead to a thoroughly acceptable musical result; but inasmuch as these details themselves are very largely dictated by the principles of harmony and correct chord-progression (without which no style of music can be faultlessly constructed), it follows that constant regard of fundamental harmonic laws must facilitate the application of the detailed contrapuntal rules. As already stated (par. 11), the influence of the original harmonic principles is chiefly exhibited wherever disjunct movement is employed; but it is never absent, and is the remote power which directs even conjunct movements. The laws of harmonic (chord) succession may be summarized as follows:

I. Diatonic (within one key).

a. Tonic chords (I or VI) can progress into any other chord of the same key, or of a different key (usually related by adjacent signature).

b. Dominant chords (V–V7–V9–0V7–0V9, the 0 indicating incomplete forms *) pass, legitimately, into Tonic chords. Other progressions are, however, possible, through the agency of Inversion (i.e., into inverted forms of the otherwise inaccessible chords).

c. Second-dominant, or sub-dominant chords (the II–IV–II7 –IV7 **) pass, naturally, into Dominant chords. But their progression into Tonic chords is entirely permissible; best, however, into inverted forms of the latter.

d. Subordinate Triads (II, VI, III,) cannot progress into their respective principal Triads (IV–I–V) except by inverting the latter.

e. The III passes legitimately into the IV or VI; into other chords rarely, and only upon inversion, as above.

* Triad and 7th-chord on the Leading-tone. See the Author’s “Mat. of Mus. Comp.,” par. 187 par. 198.

** Idem, par. 206, 407.

f. Any chord may be repeated within the same rhythmic group, but, as a rule, not into a unit which is more accented than that upon which the chord began. This rule, however, is also moderated somewhat by inversion, i.e., change of bass tone at the accent.

II. Chromatic.

g. If the chromatic inflection is employed, any reasonable chord-succession is feasible, subject to par. 2a, and [par.] 2b.

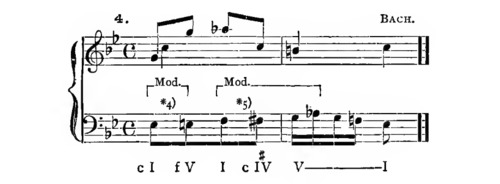

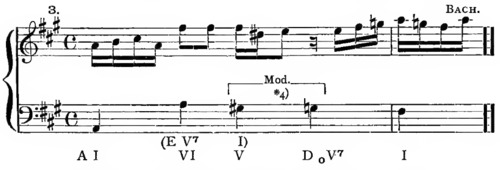

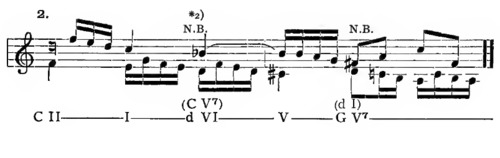

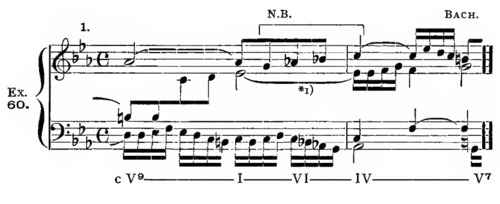

The most vital of these rules are a, b, and c, — particularly b. For illustration:

[Two-Part Invention no. 1 in C major, BWV 772, mm. 2–4]

[Two-Part Invention no. 4 in D minor, BWV 775, mm. 3–7]

[Fugue No. 18 in G♯ minor, BWV 887, from WTC Book II, mm. 5–7]

[Fugue No. 12 in F minor, BWV 881, from WTC Book II, mm. 5–8]

[52-5: Fugue No. 17 in A♭ major, BWV 862, from WTC Book I, mm. 2–4]

[52-6: Two-Part Invention no. 9 in F minor, BWV 780, mm. 3–4]

*1) See par. 4a, (1).

*2.) See par. 10.—

*3) The effect of this semi-essential perfect 4th is moderated by the embellishing tone e (par. 17a).

*4) The ear places the simplest and best construction upon every harmonic effect; therefore this is more likely to sound like (and to be) a Dominant chord, than the subordinate II.

*5) Comp. note *4). In this whole example the harmonic formations are very clear. See also par. 3a.

*6) The majority of these 8th-notes are essential.

*7) *8) There are here two striking illustrations of the rule given in par. 17b. The progression of the upper part, at note *7), is not interrupted, though it collides quite harshly with the lower part at the accent. Compare par. 7. The still harsher collision at note *8) is justified by the sequential formation of the lower part. Comp. par. 13i.

*9) The skip of an augmented 2nd is justified by chord-repetition and straightforward part-progression (par. 4c).

*10) Comp. note *7).

See also Ex. 51-3 (harmonic analysis).

h. In the conduct of the lowermost part, the treatment of the chord 5th (as obvious 6–4 chord) should be guarded. The established rules apply here also:

- Avoid leaping either to or from a bass tone that is obviously the 5th of the momentary chord, always excepting during chord-repetition. (Comp. Ex. 50, B.)

- Avoid a succession of 6–4 chords. These are always betrayed by parallel fourths between the upper and lowermost parts, when the 4ths are both essential. (Comp. par. 17e.)

- Further, it is unwise to place any 6–4 chord in a very conspicuous position; hence, it should not appear as very first, or as last, chord of a sentence.

See also par. 62, where these rules are more exhaustively illustrated.

EXERCISE 3.

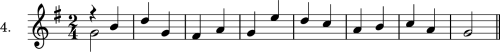

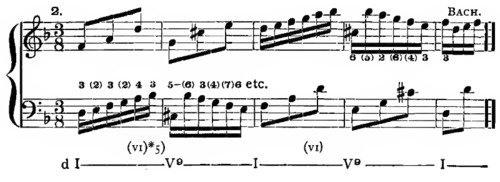

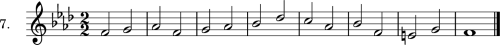

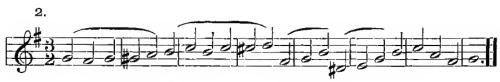

To each of the following melodies a second part is to be added, according to paragraphs 16, 17, and 18, and the following directions:

The rhythm of the added part is to be more active than that of the given part, so that two, or three, or four tones accompany each beat of the latter, uniformly.

Each melody to be manipulated twice, as in the preceding Exercise, adding upper and lower part; and each melody is to be counterpointed throughout in a uniform rhythm of two, three, or four notes to each beat, in the following order:

- Adding lower part, 2 notes to each beat;

- Adding upper part, 3 notes to each beat

- Adding lower part, 4 notes to each beat

- Adding upper part, 2 notes to each beat

- Adding lower part, 3 notes to each beat

- Adding upper part, 4 notes to each beat

It will be well to use two staves (G and F clefs). The added part need not be limited in compass, but it should not diverge an unreasonable distance from the given one; and, as a rule, the parts should not cross.

No modulations (changes of key) are to be made in this exercise.

Rests may be used, sparingly; as a rule, only at the beginning of an occasional accented beat. The added part always begins with a rest, as indicated.

Review the directions given in Exercise 2; and refer constantly to the rules of pars. 16, [par.] 17, [par.] 18, especially the note following Ex. 41; par. 17b; [par.] 17f [par.] 18b; [par.] 18f, g. See also Ex. 8; Exs. 9A and [ex. 9]B; Exs. 5 and [ex.] 17; Exs. 24 and [ex.] 25; par. 7; par. 8; par. 8b. And review the “Summary,” par. 13; par. 21b.

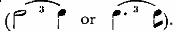

*1) When the added part has three notes, this figure becomes  or

or  (see Exercise 6, note *3).

(see Exercise 6, note *3).

*2) The added melody may end simultaneously with the given part, but it is far better to carry it along, as here, up to the next beat. The final tone must be the Tonic.

*3) When used as lower part, this first tone will be the Root of the Dominant chord.

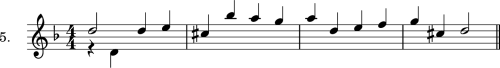

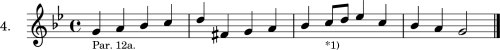

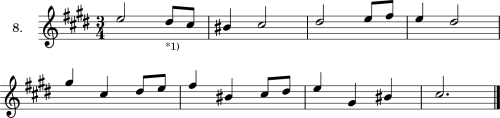

EXERCISE 4.

To each of the given melodies of Exercise 3 a second part is to be added, as before, in uniform rhythms of two, three, or four notes to each beat, — but introducing a tie, from the last note of one group (beat) to the first note of the next, as shown in the subjoined illustrations.

Review, very thoroughly, par. 9, especially [par. 9]f; and observe the following specific rules for the treatment of the tie:

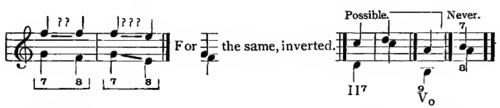

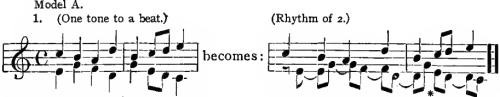

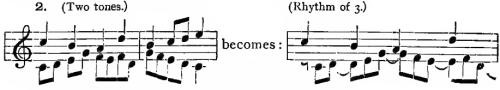

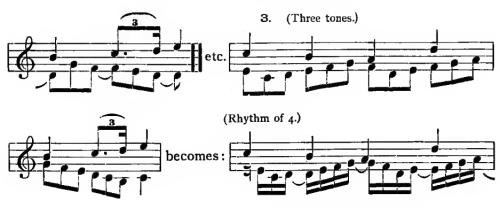

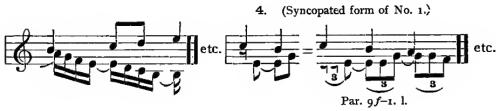

Rule A. The tie may be applied to any of the preceding (uniform) species of counterpoint with one, two, or three notes to a beat, and results in a faultless syncopation of the same, representing, in each case, the next higher grade of rhythmic motion; i.e., the original formation of one note to each beat becomes one of two notes, two notes become three, and three become four. No further serious condition is involved than that the original formation be uniform rhythm, and faultless. Thus:

* The tie must be omitted here, for an obvious reason.

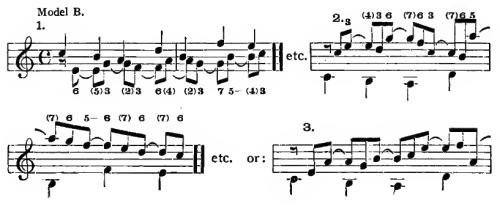

Rule B. A far more comprehensive and fruitful application of the tie is governed by the following directions, to which, for that reason, preference should be given:

(1) The last note of each group (that from which the tie is made) should, as a general rule, constitute one of the good intervals, defined in par. 15 as valid for the essential tones, — especially par. 15, a and [15]b.

(2) The first note of the next group (that which is tied over from the preceding group) may be any interval, but should be, if possible, a dissonant one, representing a good suspension. If this is the case, it is not so necessary that the preceding interval be a faultless one (par. 15).

(3) If the first note of the group be, thus, a dissonant interval, its movement is governed by the rules of par. 9f; the best progression is the stepwise resolution, upward or downward (most frequently the latter) into one of the “good” intervals; a repetition of the tone, however, before this resolution, is very common and invariably permissible. For example:

(4) It is generally very undesirable to reverse the rule of clauses 1 and 2 above; namely, to tie a poor interval over into a good one:

Note. — In some of the solutions in  measure the tie may be omitted at the second and third beats, and used at the bar only; in

measure the tie may be omitted at the second and third beats, and used at the bar only; in  measure, it may be omitted at the unaccented (2nd and 4th) beats, or, occasionally, be used at the bar only. Such omissions should, however, be made uniformly throughout.

measure, it may be omitted at the unaccented (2nd and 4th) beats, or, occasionally, be used at the bar only. Such omissions should, however, be made uniformly throughout.

The tie must be omitted, further, at longer tones in the given melody,—for instance, in melodies Nos. 6 and 8, at the second beat of each half-note.

Each melody may be manipulated in the six different ways specified in Exercise 3.

Modulation.

19. The rules of harmonic progression, given above, also govern the movements of the parts in modulation, i.e., in passing from one key into another.

a. It is always safe, generally necessary, to close each key upon some form of its Tonic harmony (I or VI); to pass from this into some Dominant or Second-dominant chord of the desired key, and from this into its Tonic harmony. Comp. par. 18a, and [par.] 18b and [par. 18]c. This modulatory formula is the most common and reliable, whether effected exclusively by diatonic successions, or involving a chromatic inflection (see par. 19). It is least binding for modulation into the Relative key (i.e., the key with the same signature); and, of course, it is subject to numerous modifications, especially upon the grounds of par. 17b, — unconstrained melodious conduct of the individual parts. For example:

[Two-Part Invention no. 1 in C major, BWV 772, mm. 3–4]

[Two-Part Invention no. 4 in D minor, BWV 775, 7–10]

*1) From a Tonic chord of the first key into a Dominant chord of the desired (next-related) one.

*2) From a Tonic chord of old key, into a Second-dominant, and then Dominant chord of new key.

[Two-Part Invention no. 7 in E minor, BWV 778, 9–11]

[Fugue No. 16 in G minor, BWV 861, from WTC Book I, mm. 21–22]

*3) From the VI (subordinate Tonic chord), into Second-dominant and Dominant chord.

*4) Chromatic inflection in Bass.

*5) The f♯ is a raised fourth scale-step only,— not the index of a Modulation; it is evident that no other key than c-minor is present.

b. The principal exception to this fundamental rule of modulation is occasioned by the chromatic inflection; this melodic device, as stated in par. 18g, if properly applied (par. 2a, [par. 2]b), renders every rational harmonious succession possible and acceptable.

For illustration:

[Two-Part Invention no. 11 in G minor, BWV 782, mm. 1–3]

[Fugue No. 12 in F minor, BWV 857, from WTC Book I, mm.5–7]

[Prelude No. 19 in A major, BWV 864, from WTC Book I, 1–2]

*1) In both of these cases the first key is abandoned at one of its Dominant chords, but chromatically.

*2) This illustrates the establishment of the new key through its accented Tonic -  - chord, which stands for a Dominant harmony. —

- chord, which stands for a Dominant harmony. —

*3) Change of mode, from one Tonic harmony into the other. —

*4) Compare note *1). The bracketed analysis is extremely doubtful. See, further, Ex. 44, No. 6.

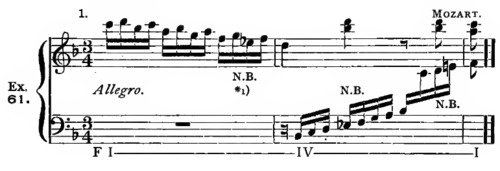

c. Another somewhat exceptional, though highly effective, modulatory device consists in introducing an unexpected accidental in the course of a part-progression, whereby the essential tone involved receives an unpremeditated chromatic inflection (not affecting the letter); or, in other words, a foreign tone is substituted for the expected one, so as to divert the melody and lead abruptly, but perfectly smoothly, into a new (usually closely related) key. Such a “Substitution” may take place at almost any point; but, of course, only where either tone (with or without the accidental) constitutes an equally correct and natural melodic progression from the preceding ones. It is usually safest at accented beats, or accented fractions of beats, and after a Tonic impression of the former key has been imparted — no matter how brief. The parts must be conducted, after the substitution, in a manner calculated naturally to confirm the new key. For illustration:

[Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 851, from WTC Book I, 4–5]

[Two-Part Invention no. 8 in F major, BWV 779, 14–15]

[Two-Part Invention no. 2 in C minor, BWV 773, 21–22]

*1) By inserting the sharp, the expected c (as part of the expected I of C major) becomes c♯, and the modulatory current is deftly turned from C into d minor. In the following measure the expected V of d minor is averted by changing the accidental before c from ♯ to ♮. —

*2) B-flat is substituted for the expected b-natural. In the next measure a sharp is substituted for the natural before f. In each case, the expected chord, which would have confirmed the natural harmonic succession, Is indicated in brackets.—

*3) G♮ is substituted for g♯

*4) E♭ is substituted for e♮.—

*5) The ♮, substituted for the expected ♯ before this prominent f, is an almost unwelcome surprise. —

*6) This unexpected c-natural leads to the unique mod. into F major. See, further, Ex. 32, third beat; e♮ instead of the expected e♭— Ex. 57, note *6).

How peculiarly prolific and potent this seductive little device may prove to be when skilfully employed, and how perfectly natural and justifiable its operations may be when prudently conducted, is shown by the following test, in which, it is true, the best possible conditions are provided by the sequential formations (comp. par. 13i):

Original form without Modulation:

Modified by Substitutions (accidentals):

or, if the most extreme treatment be justified or demanded:

*1) The accidentals suggested in the brackets above are doubtless too “extreme”; though they might, perhaps, be justly adopted in slower movement.

*2) The comparison of these two widely different terminations of one and the same series of letters, with the same starting-point, proves that any modulatory design may be speedily realized by judicious application of this principle of “substitution.” Still, as with all other somewhat irregular factors of musical texture, its best results are emphasized with peculiar effectiveness by moderation. A very striking, almost startling, example of substitution occurs in Bach, Well-tempered Clavichord, Vol. I, Fugue 20 (a minor), measure 14, beat 3, g♯ in tenor, which abruptly follows g♮ in the soprano. This change is due to the modulatory design as a whole.

d. Finally, any reasonable irregularity with regard to the method of modulation, or the choice of key, is justified at a Cadence, or at any obvious point of separation between members of the structural design (i.e., between Sections, Phrases, Motives or Figures; the latter, especially, when sequential in arrangement; compare par. 13i). For illustration:

[Two-Part Invention no. 4 in D minor, BWV 775, 37–39]

[Two-Part Invention no. 7 in E minor, BWV 778, 13–14]

[Two-Part Invention no. 6 in E major, BWV 777, 27–29]

[Two-Part Invention no. 15 in B minor, BWV 786, 2–3]

[Fugue No. 24 in B minor, BWV 869, from WTC Book I, mm. 4–5]

[Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 847, from WTC Book I, mm. 18–19]

*1) The irregularity here consists in passing immediately from a minor into g minor (non-related keys), at — i.e., after — the cadence.

*2) Similar, — from b minor into a minor. In each of these cases, however, the chords employed accord with the rule (par. 19a).

*3) Here the keys are related, but the modulatory process is irregular — from I into I.

*4) Similar (from V of the old key into I of the new).

*5) This extraordinary series of modulations is justified by the sequential formation of the lower part. The unessential intervals are in brackets. The c♮ in Soprano is the minor 9th (lowered 6th scale-step) of E.

*6) The a♯ in Bass is substituted for the expected a♮ (par. 19c).

*7) Here the chromatic successions are made in an irregular manner, involving the Cross-relation. They are rectified by the Sequences.

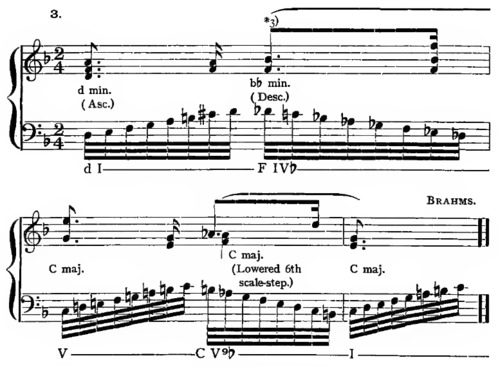

20. The notation of the minor scale depends chiefly upon the harmony, and is subject to the following rules:

a. The harmonic form (lowered 6th step and legitimate leading-tone) is rarely used, though possible during the Dominant harmony. — See Ex. 52, Note *9). —

b. The melodic forms, with raised 6th scale-step in ascending and lowered 7th step in descending, are used during Tonic harmonies. Thus:

[Sinfonia No. 2 in C minor, BWV 788, 25–26]

(An illustration in three-part counterpoint is given, because of the superior distinctness of the harmony.)

c. The “ascending” form (with raised 6th step) is used in preference to the harmonic form, in descending also, when the harmony is Dominant; this is because of the proper leading-tone (7th scale-step), which is characteristic of the Dominant harmony, and not to be altered. Thus:

[Sinfonia No. 2 in C minor, BWV 788, mm. 26, 27, 19–20]

*1) The a♮ is used, instead of a♭, because of the b♮ which is indispensable in the Dominant harmony.

*2) Here d♮ is used in Bass, in descending, although it clashes very harshly with the d♭ in the Soprano.

*3) The a♭ in Bass illustrates the force of the rule in par. 17b. It is even doubtful that this a♭ is an essential tone, though it indicates the Tonic chord (expected at this accent) quite forcibly, and thus imparts the appearance of suspension-harmony to the upper tones. At all events, whether essential or not, the a♭ is “picked up” again at the next accented unit (4th beat) and disposed of in conjunct movement; and, further, the whole 16th-note passage is sequential.

d. Inversely, the “descending” form (with lowered 7th scale-step) may be used in ascending also, when the harmony is Sub- (or Second-) Dominant; or when it is Tonic, immediately followed by Subdominant. This, however, is far rarer than the foregoing.

For illustration:

[Prelude No. 7 in E♭ major, BWV 852, from WTC Book I, 52–53]

*1) In both of these cases the notation is influenced by the coming Subdominant harmony. See par. 20e.

e. These exceptional regulations will be seen to corroborate the general rule that the notation of all passing-notes usually conforms to the scale represented by the chord upon the momentary beat, — or by the chord upon the next-following beat (if near enough to be affected by the latter rather than by its own beat).

Illustrations are very numerous, in classic writings, of this rational principle of defining the notation of all passing-notes which fall within the limits of a certain chord, as if that chord were, for the time being, a “Tonic” chord. Apparently, it is most commonly the coming chord that exercises this dominating power. Exceptions are found, where the influence of the momentary chord is weighty enough to overpower that of the coming one; and, further, at cadences and other points of separation (alluded to in par. 19d), where abrupt effects are desired.

General Illustrations:

[Mozart: Piano Sonata in F major, K. 547a, I, mm. 187–189]

[Two-Part Invention no. 4 in D minor, BWV 775, mm. 41–43]

*1) There is scarcely sufficient proof that a genuine, decisive modulation from F into B♭ is here being made; the distinctive tones (e♭ and e♮) are so unessential in effect, that they do not appear to cancel the prevalent F-major impression. The e♭, and e♮, near the end of each measure, are chosen to blend with the scale-quality of the coming chord. The e♭ on the second beat of the measure conforms to the momentary chord.

*2) This whole measure is, more than likely, the Tonic harmony of F; the letters b and c are so inflected as to blend with the coming d-minor chord; but b♭ and c♮ would sound quite as well, as far as that measure alone is concerned, or if the key remained unchanged.

*3) A modulation takes place at this point, from d minor into F major, through the altered IV of the latter (with d♭, the lowered 6th scale-step); this chord representing the Tonic harmony of b♭ minor, the passing-notes follow the line of that scale, in descending succession. The analysis of actual key-conditions is noted below the brace; that of the scale-conditions governing each group of passing-notes, is given between the staves.

f. The same rule applies also to the upper one of the two neighboring-notes which attend each chord-interval. The notation of the lower neighbor may either correspond, likewise, to the momentary scale, or it may be a half-step (minor second) below its principal tone; the former notation is generally chosen in stately, more serious polyphony; the latter in lighter, more lively, music. For example:

[Fugue No. 5 in D major, BWV 850, from WTC Book I, m. 24]

[62-2: Fugue No. 5 in D major, BWV 850, from WTC Book I, mm. 17–18]

[62-3: Prelude No. 2 in C minor, BWV 871, from WTC Book II, mm. 13–14]

*1) The chord upon this beat is manifestly a II (of D major), but, representing e minor, the upper neighbor within its radius is written c♮.

*2) All of these lower neighbors (marked o) confirm the scale (D major).

*3) The lower neighbor is here persistently the half-step, despite the key, and the a♭ above.

*4) This lower neighbor confirms the scale, — as is the case with nearly all the neighboring-notes in the entire composition (W.-t. Cl., Vol. II, Prelude 2 — which see).

*5) Lower neighbor the half-step, but evidently influenced by the coming chord (key).

*6) The lower neighbor of the Leading-tone (7th step) is almost always a whole-step.

Summary.

21a. In two-part Polyphony, the intervals of the 3rd and 6th prevail, and govern the majority of simultaneous essential tones.

The perfect 8th and 5th, — diminished 5th and 7th, — augmented 4th and 2nd, — govern occasional essential tones, when they represent rational harmonies.

All positively objectionable intervals must be the obvious modification of some permissible interval (defined by the harmony).

b. Each part must be so conducted as to constitute, by itself, a perfect, interesting, and well-formulated melody, independent of its fellow-part. In order to verify this, the student must play or sing his added part alone, after each melodic task is completed.

Further, the parts are conducted, generally, in opposite directions.

c. The concerted operations of the two parts must be in manifest keeping with the laws of harmonic (chord-) progression, and modulation.

Principal exception: par. 18g.

d. Smooth and effective modulatory inflections (transient or definite) may be made by the substitution of an inflected tone (by an unexpected accidental) for the expected scale-tone, at the appropriate time and place.

e. The notation of passing-notes, within a certain narrow harmonic range, is defined upon the assumption that the chord which governs that range is temporarily the representative of the corresponding key (usually as Tonic chord), irrespective of its actual name in the prevailing tonality.

f. Sequential (or generally symmetrical) formations justify any not unreasonable dissonance, irregularity of melody, harmonic succession, or modulation.

EXERCISE 5.

A. Analyze the harmony and the notation of Bach, Well-tempered Cl., Vol. I, Prelude 10 (e minor).

B. Fill out the Bass part of the following phrase, in scale-runs of 32nd-notes, as on the first (given) beat; observing the rules of Notation given in par. 20 (particularly 20e); refer to par. 21e.

C. Manipulate the following phrase according to the principle of Substitution expounded in par. 19c (particularly Ex. 56). Any signature may be chosen for the beginning; and the introduction or substitution of modulating accidentals, in the course, is to be freely practiced. The Cadence is to be completed, each time, upon the 3rd beat of the last measure, with the Tonic harmony of the appropriate key:

D. Add a second part to each of the following melodies, with reference to pars. 19 and [par.] 20, and in the manner described in Exercise 3, namely: each melody to be used alternately as upper and lower part, and the added part to be in a uniform rhythm of either 2, 3 or 4 notes to each beat, successively. A few experiments may be made with ties (syncopation), as shown in Exercise 4. Refer to par. 21, [par. 21]b, [par. 21]c, [par. 21]d, [par. 21]f.

*1) Scan the melody first as a whole, and determine, at least approximately, where and what changes of key are likely to be necessary.

*2) For 3 notes

*3) For 3 notes