CHAPTER VI.

The Contrapuntal Association of Three Melodic Parts (Voices).

59. Review the definition of Polyphony given in the Introductory Statement (page 1).

The “harmonious” association of three co-ordinate melodies must necessarily be controlled by the conditions of chord-structure to a far greater and more manifest extent than that of only two voices, — for which latter a schedule of euphonious intervals was found to suffice.

For this reason 3-voice Polyphony exhibits a much more evident harmonic character than the 2-voice; and the chief difficulty in its successful manipulation consists in respecting and enforcing the control of the Chord-forms, without fettering the individual parts and interfering with that independence and melodic smoothness which is, in true Polyphony, as significant a requisite as that of unanimous action.

60. The chord-forms, i.e., any combination of three or four 3rds, with or without inversion, afford the necessary consonance or general “harmony” of effect. But an excess of this harmonic (i.e., homophonous) effect must be counteracted, by modification (through inharmonic adjuncts) sufficient to disguise the chords, as such, and create the impression of individual voice-movements within the channels marked off by the chord-tones. The problem of genuine and effective Polyphony for more than two parts is, concisely stated, that of achieving this impression of independent melodic progressions, and still preserving sufficient evidence of the chords to ensure a harmonious result.

Technically considered, this is secured by the employment of Suspensions, Passing-notes (accented and unaccented), and occasional Neighboring tones or Appoggiaturas, as disguising adjuncts of the predefined chords, as evidences of freedom and elasticity in a movement whose general direction is dictated by an underlying stern principle of harmonic necessity. But the manner and the extent of the use of these inharmonic (dissonant) factors must be vigilantly guarded, and tempered by due consideration of the demands of euphony and harmony. Review par. 17b.

Details of Three-Voice Polyphony.

61. a. This imparts a corresponding degree of importance to the harmonic idea, and greatly emphasizes the rules of chord-succession given in pars. 18 and [par.] 19, which must be carefully reviewed.

b. Of the three parts, two will very likely co-operate temporarily according to the rules of 2-voice polyphony given in Chapter II; and the remaining (third) part aims to secure some essential tone which, with the essential tones already present, completes some legitimate chord-structure.

This rule is merely stated for the convenience of the student, who, as beginner, can scarcely expect to conduct three independent parts successfully, all at once, but will need some such division of the labor as the rule indicates. He must observe that no attempt can be made to intimate which two of the three parts will be chosen thus to form the temporary basis of the contrapuntal fabric, or how far the choice each time extends; for that depends upon conditions that are either self-evident, or follow as a matter of course out of later details, — especially par. 64. And in any case the rule does not refer to a certain pair of voices throughout, but implies a temporary choice, liable at any moment to be exchanged for another pair. The ultimate consideration is, after all, that the three parts together must represent, in their simultaneous essential tones, some legitimate chord-form.

Hence, in the preliminary draught of the three-fold melodic association, the intervals of the 3rd, 6th (8ve, etc.), will govern the choice of simultaneous essential tones, as shown in pars. 14 and [par.] 15. For illustration:

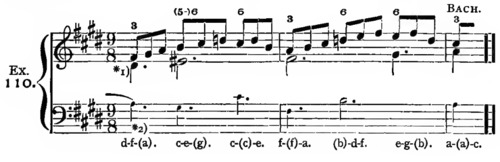

*1) Assuming (arbitrarily, simply by way of illustration) that Bach defined first the conduct of the two higher parts, it will be seen that they conform exactly to the rules of 2-voice counterpoint, and represent, in their essential tones, fragments of successive chords, whose absent intervals afford the staple out of which the additional (3rd) part is constructed.

*2) The notes of the lower part correspond to the letters in parenthesis, and represent, in nearly every case, the tones which complete the chord-structure.

Further:

*1) Assuming, as above, the small notes to represent the added (3rd) part, the same process may be traced. See also Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. I, Fugue 3, measures 1–7. Here the process of adding first one part to the given motive, and then a third to these two, is actually employed; the upper and inner parts of measures 3–4 become the inner and lower parts in measures 5–6, with transposition and very slight change; to these a new part is added, above. See par. 66a.

Vol. I, Fugue 13, first 6 measures; the same, in every particular.

Vol. I, Fugue 18; the lower and inner parts of measures 3–4 become inner and upper parts in measures 5–6, with transposition, while a third part is added, below.

Vol. I, Fugue 23; the same.

Vol. II, Fugue 16; the same (measures 5–8 increased to three parts in measures 9–12).

Vol. II, Fugue 23; the same (measures 5–8 increased to three parts in measures 10–13).

c. As stated in par. 60, second clause, the harmonic points thus definitely fixed as basis for the conduct of the additional (3rd) part, should be so modified or disguised by means of auxiliary tones, unessential neighboring and passing-notes (inharmonic tones, in a word), as to counteract the impression of simple chord-succession. This device is omitted in Ex. 110, but plainly seen in Ex. 111, No. 2; and may be verified in the other given illustrations, also.

But this is not all; the insertion of passing-notes must not be adopted as a device to this end alone, or the texture will, after all, amount to no more than “embellished harmony.” A higher purpose — that of independent melodic progressions — must dictate the employment of such inharmonic tones; and while the progressions must necessarily be governed by the chord-contents, their independence must be ensured by sufficient evidence of thematic purpose. Review, in this connection, par. 17b, (pars. 13i, [par.] 21b); also par. 7.

d. Of the purely mechanical means of obtaining voice-independence, none is more efficient and indispensable than the Tie, which advances in importance in proportion to the number of polyphonic parts associated. Review thoroughly par. 22d, and par. 9, entire. For example:

*1) Some of the ties in this sentence result in positive dissonance, by producing Suspensions; at other places, on the contrary, the tie simply modifies the rhythm of its part, without influencing the consonant effect. See also Ex. 57, No. 6 (ties in lower part); Exs. 58, [ex.] 59, [ex.] 60; Ex. 111, Nos. 1 and [ex 111]-2; Ex. 113.

e. The greater the number of parts employed in a polyphonic complex, the greater the likelihood and necessity of indirect coincidence between a certain pair of them, — to counteract the danger of excessive dissonance from the independent movements of so many individual parts. This is probably most frequently exhibited in the prevalence of parallel movement in 3rds or 6ths, between two of the three (or more) voices, — a trait which is strikingly common in the best examples of Polyphony, and affords the surest guaranty of smooth and euphonious effect. The limit of such a parallel series of 3rds or 6ths can be defined only by a perfect understanding of the momentous principle stated in par. 60, and of the “spirit of Polyphony” in general. Sometimes (as if to redeem the independence of the parts, or perhaps for thematic reasons) the line of parallel 3rds or 6ths is disguised by some means; for instance, in Ex. 112 the inner part is obviously defined in parallel 3rds with the upper, from measure 4 to 8; but by embellishment, first in one part and then in the other, their indirect coincidence is completely veiled. See further:

*1) Measure 1, beat 2,— 6ths between outer parts (up to first pulse of next beat); beat 3, — 6ths between inner and lower parts (again up to first pulse of next beat); measure 2, beats 1 and 2, — 3rds between outer parts, disguised by the omission of alternate 16ths in upper part (again the parallels extend into the following beat, modified by transferring the last tone to the higher octave); beat 3, — 3rds between inner and lower parts. See also Ex. 57, No. 6; Ex. 111, No. 2.

Of similar (though far inferior) efficiency is that variety of indirect coincidence in which two of the parts reciprocate in the embellishment of chord-tones that lie a 3rd apart,— both using the same tones, but in contrary direction. Thus:

Bach uses this device so rarely, as compared with his employment of parallel 3rds and 6ths, that it may justly be regarded with suspicion, as a polyphonic factor. See Beethoven, Pianoforte Sonata, op. 106, first movement, measures 55–61.

f. All general rules of contrapuntal association (as those of par. 17d and [17]e; pars. 18, [par.] 19, [par.] 20) apply alike to every variety of polyphonic texture, regardless of the number of parts employed. The rule in par. 17f, with reference to conducting the parts in contrary (opposite) directions, applies to polyphony for three and more parts also, but with certain modifications. It is evident that all three (or four) parts cannot move at the same time in different directions; but it is possible (1) to hold one part level, while the other two are respectively ascending and descending (or even moving in parallel direction); (2) to carry one part, at least, in contrary motion with the other two, so that one descends while two are ascending, or vice versa. It is wise to conduct the two outer parts in opposite directions, as a rule, and to avoid parallel movement in all three parts at once.

Of peculiar value in 3-voice polyphony is the device of modulatory Substitution expounded in par. 19c, which is to be thoroughly reviewed.

62. The conduct of the lowermost part is of increased importance in 3-voice polyphony, because of the more pronounced harmonic character of this species of writing (par. 59), and the consideration due to those forms (Inversions) of harmony in which the chord-fifth lies lowermost (i.e., the 6-4 chords).

It is, of course, impossible (and needless) to shun this chord-form altogether; but vigilance must be exercised in the treatment of all obvious 6-4 chords. Former rules apply strictly; see par. 18h. To recapitulate:

a. Avoid leaping to, or from, a bass tone which is manifestly the 5th of the momentary chord, — excepting in chord-repetitions.

b. Avoid a succession of chord-fifths in the lowermost part (i.e., 6-4 chords) when both represent Consonant forms of harmony; if either of them is an imperfect 5th, or the inverted form of any Dissonant harmony, the succession is good. This grave error is most easily checked by avoiding parallel perfect 4ths with the Bass, in the conduct of any upper part, when the 4ths are both essential intervals (par. 14).

c. Avoid any very conspicuous 6-4 effect, excepting when the harmony is Tonic. Avoid, hence, beginning or ending a Section upon a 6-4 chord. As a rule, the lowermost part should not be announced (or re-announced after a rest) upon the 5th of the momentary chord; nor should it discontinue (pass into a rest) after a tone which is evidently the chord-fifth.

d. These rules may be said to apply to all 6-4 chords excepting that of the Tonic; the latter is largely, if not entirely, exempt.

For example:

63. The rhythmic conditions of 3-voice Polyphony are identical in principle with those of the 2-voice, as detailed in par. 22, which review.

a. The chief rule is stated in par. 22a: the three voices participate, with a certain regularity of alternation, in sustaining the adopted rhythmic movement (of [8th] notes, [16th]-notes, — or whatever the prevailing uniform rhythm may be). Rhythmic diversity between the parts being, as repeatedly emphasized, the principal means of instituting voice-independence, it is evident that its importance, and the necessity of its careful treatment, increase in proportion to the number of parts engaged. Review, very thoroughly, par. 22a and [22]d.

Quite frequently the same rhythm will be given to two of the parts simultaneously; but this similarity must never be carried very far (best not more than 2, 3, or 4 beats), before being transferred to another pair, or abandoned temporarily in favor of one part alone. See Ex. 114, No. 2, [Ex. 114, ] No. 3; Ex. 113; Ex. 111, No. 1.

One of the three parts may run on in uniform rhythm almost indefinitely, if sufficient provision for diversity is made in the remaining two parts. See Ex. 110 (Soprano); Ex. 113 (Bass); Ex. 114, No. 2, [Ex. 114, ] No. 3.

As a general rule, the most definite and constant aim is, to assign to each of the three parts, temporarily, a different rhythmic movement, i.e., different tone-values; not obstinately, but as an ever-conscious preference. This, and the maintenance of a smooth, uniform, collective rhythmic effect, satisfy, together, all the rhythmic demands of polyphonic texture.

See Ex. 110, — different values in each of the three parts; Ex. 111, No. 2,—during almost every beat the three parts have different values; Ex. 112, the same; Ex. 113, measure 2. This may best be verified by careful analysis of the given references.

Finally, the exchange of one rate of rhythmic movement for another (faster or slower) may, of course, be effected within the same Invention without confusion, if care be taken to preserve good balance of total effect (by regularity of recurrence, — on the principle of par. 22e), and a perfectly clear impression of the fundamental metric design. See Bach, 3-voice Inventions, No. 15 (alternating [16th] and [32nd]-movements); No. 2; and Ex. 117, with context (par. 70).

b. The Rest enters into the rhythmic design of Polyphony more significantly when three or more parts are used than when there are but two. Review par. 10, and par. 22d, last clause.

In general, short rests, interspersed promiscuously through the polyphonic texture, are of inferior value, and often rather injure than improve the effect. It is far more judicious to interrupt the conduct of one of the three parts by a longer rest, for a whole measure or more, so that a decided and noticeable change of volume results.

A part may be thus definitely discontinued (1) at any cadence; or (2) at any point in the course of a Section where the part reaches a tone that has no special obligation or tendency to fulfil, — especially when it is any interval of the Tonic harmony; and, as a rule, only at an accented beat or the accented fraction of a beat; rarely, if ever, after any dissonant tone that demands resolution.

In 3-voice Polyphony, generally no more than one part should rest at a time (unless it be very briefly); hence, another part must not be discontinued until the absent part has fairly recommenced; in other words, the extremities of a discontinuing and recommencing part should overlap noticeably.

After a protracted pause, the part may recommence with an announcement of the Motive. This is the most appropriate and effective method, but is by no means essential.

c. Further, the part should recommence, after a rest, on an unaccented beat; or, still better, on a fraction of the beat, as a very general rule.

For illustration of all these points, see Ex. 112, inner part; Ex. 113, lower part; Ex. 114, Nos. 2 and [114]-3; Bach, 3-voice Inventions, No. 1, measure 13 (Bass), 15 (inner part), 16 (lower part pauses directly after inner part recommences, overlapping one beat), 17 (brief rest in upper part). 3-voice Invention No. 2, — in measures 5 and 6, the outer parts pause together during the last beats; this is unusual, but the reason is obvious; the irregular acceleration of the rhythm in the inner part (contrary to the fundamental principle, par. 63a), is fully justified by its recurrence, or sequence, in the following measure, and again, at intervals, throughout the Invention. Compare pars. 22e and [par.] 21f. In this same Invention, measure 4 from the end, the lower part discontinues precisely as the upper part recommences, i.e., without overlapping; this is least confusing when, as here, the parts in question are so distant from each other that their extremities cannot be confounded. In nearly or quite all of these cases, the rule of par. 63c is illustrated conclusively.

Leading Parts.

64. It is extremely difficult—for the beginner, almost out of the question — to lead three polyphonic parts abreast, and preserve the individuality of each part as if it were alone. Before this supreme command of simultaneous part-leading shall have been acquired, the student must adopt some method of systematic division of the labor, by centering his attention upon first one and then another single part for a time. This is entirely feasible and justifiable, because it is consistent with the processes of polyphonic texture, that a certain one of the three (or more) parts temporarily takes the lead, — the other parts meanwhile deferring to the “Leader,” as simple contrapuntal associates, until some other part, in its turn, assumes the lead.

The choice of temporary “Leader” may be made arbitrarily; but it is far more likely to determine itself, as a matter of course, out of the natural conditions and exigencies of the progressive development. For example, that one of the three parts which has charge of the Motive invariably assumes the leadership for the time being; and, during episodes, that part takes the lead which pursues the most obvious and important thematic purpose, — as, for instance, the projection of a line of Sequences, the pursuit of some significant imitatory process, or any other definite and far-reaching melodic or structural aim.

Further, it is precisely the same with the question “how long” a part may assert the leadership, before abandoning it to some other part; it depends upon the conditions which determine the choice in the first place; it may be a measure or several measures, or possibly only a single beat.

In any case, the leading part should be written down alone, as far as it is to extend; it is then comparatively easy to return and “fill out” the remaining parts.

This idea is closely allied to that expounded in par. 61b, which review.

See Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 1; during measure 1 the upper part “leads”; during measure 2, the inner part; measures 3, 4, and 5, the lower part; measure 6, the inner; measures 7 to 9 (beat 3) the lower part “leads,” first with its Sequences and then with the Motive; measures 9 (beat 3) to 10 (beat 3), the inner part; measures 10 (beat 3) to 11 (beat 3), the upper; meanwhile, during the first half of measure 11, the lower part claims the lead, and maintains it to the end of the measure; and so forth. The student is to continue the analysis to the end of the Invention, with reference to the “leading parts.”

Summary.

65. a. The simultaneous essential tones should constitute some chord-structure; and the chords should succeed each other according to the fundamental conditions of chord-progression.

b. The problem of good Polyphony for more than two parts is, to preserve an equipoise between the Consonance of the chord-forms and the Dissonance involved by independent part-conduct.

c. Ties are invaluable in effective Polyphony.

d. Parallel movement in 3rds or 6ths is the most legitimate and reliable guaranty of smooth and euphonious voice-association. At the same time, a certain degree of Contrary motion should be maintained.

e. The lowermost part must be so conducted as to avoid conspicuous or faulty 6-4 chord effects.

f. The rhythmic requirements are, to diversify the tone-values of the several parts, but to maintain a generally, uniform collective rhythmic effect.

g. Rests — especially of palpable extent—are invaluable in effective Polyphony for more than two parts. After a rest, the part should re-enter upon an unaccented fraction or beat.

h. In the execution of a multi-voice polyphonic texture, it is necessary to concentrate the attention upon a certain single part, as temporary “leader” — the choice and extent depending upon thematic conditions.

EXERCISE 18.

A. Analyze minutely, with regard to the above regulations of 3-voice Polyphony:

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 1, meas. 2–5; 10–14.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 3, meas. 4–9.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 4, last 7 measures.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 6, meas. 2–10.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 8, meas. 2–7.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 12, meas. 3–10.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 13, last 12 measures.

- Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 14, last 8 measures.

B. To some of the (corrected) examples of two-part counterpoint made in Exercises 7, 8, and 9, add a third part, — above, below, or between (or all three successively), as appears most convenient or effective. Begin the third part about one beat later than the second,—as a rule, upon an unaccented fraction of the beat (compare par. 63c). At least one tie is to be introduced, in the added part, if possible.

C. Extend the Stretto examples made in Exercise 10, to 3-voice Stretti.