CHAPTER I.

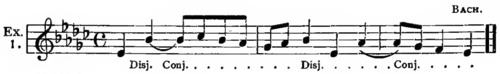

Condition 1: “Perfect Melody.” The Conduct of the Single Part or Voice.

Conjunct Movement.

1. The first and most comprehensive rule of polyphonic melody is, to lead each single part as smoothly and evenly as possible. Conjunct movement (that is, stepwise ascending or descending progression along the line of the prevailing scale) is therefore preferable to disjunct movement (that is, by leap or skip), as a general rule. Disjunct movement is, however, by no means undesirable, but should be used in moderate proportion to the stepwise movement.

* An exhaustive exposition of the fundamental laws of melodic progression may be found in the author’s “Exercises in Melody-Writing.” Thorough understanding of Chapters I–V of that book will facilitate (possibly supersede) the study of the above chapter.

[Fugue No. 8 in D♯ minor (here in E♭ minor) BWV 853 from WTC, Book I, m. 1]

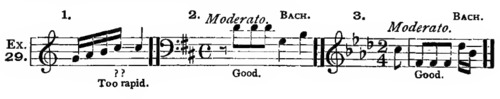

2. Diatonic conjunct movement is preferable to chromatic.

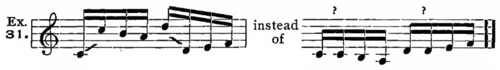

a. Chromatic successions are least objectionable in slow movement (with tones whose time-values represent whole beats, or at least halfbeats); and are generally better in ascending than in descending direction, especially when moderately rapid.

[Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor, BWV 903, mm. 1–3 (also see Example 83-10)]

[Fugue No. 12 in F minor, BWV 857 from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3]

See also Ex. 82-1; [ex.] 26-5

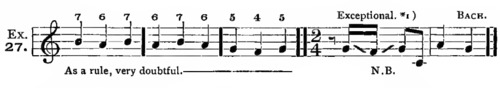

b. A chromatic succession should, if possible, be approached in the corresponding direction; and requires, almost certainly, to continue In the same direction. For illustration:

c. It is generally unmelodious to separate a chromatic succession by inserting an intermediate neighboring-tone, in quick movement:

Disjunct Movement.

3. Disjunct progressions are qualified as narrow leaps (major or minor 3rds), and wide leaps (all skips beyond the intervals of the 3rd).

Permissible Skips.

a. Narrow leaps are generally permissible.

Wide leaps, or leaps in general, are always permissible when both tones are common to the momentary chord, i.e., if they occur during chord-repetition. For instance:

[Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 884 from WTC Book II, mm. 1–4]

See also Ex. 52-2.

b. A skip of any reasonable extent (rarely beyond an octave) may be made downward to any tone whose natural tendency is upward; or upward to any tone whose tendency is to descend; — that is, the skip may be made in the direction opposite to that of the natural tendency. (These tendencies are defined in par. 6, which see.) Thus:

[Fugue No. 1 in C, BWV 846, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 15 in the G, BWV 860, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3]

These skips are, however, objectionable in the other direction (i.e., that corresponding to the natural tendency); — unless in obvious and perfect accord with par. 3a (during chord-repetition). For example:

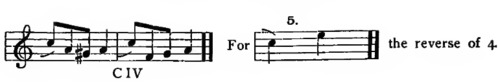

c. Almost any leap, no matter how unusual or awkward in itself, may be justified by sequence-progression, i.e., by the reproduction of a melodic figure upon other, higher or lower, scale-steps. Thus:

[Fugue No. 3 in C♯ (here notated in C), BWV 848, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

To be feasible, such a line of sequences should start from a figure that is faultless. The rectitude of the initial figure is the justification of all reasonable sequence-shifts (or reproductions) of it.

d. Unusual, and otherwise doubtful, skips sometimes occur at (immediately after) an accented tone. For example:

[Fugue No. 17 in A♭ major, BWV 886, from WTC Book II, mm. 16–17]

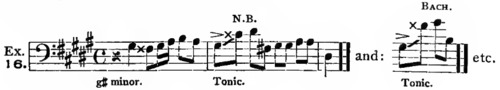

This particular passage represents, simply, a continuous scale-passage, with two shifts to the next higher octave-register, — a device which is very common and effective in contrapuntal melodies, and possible in either direction. The rule at d, however, applies to other cases also (Ex. 16).

Objectionable Skips, and Exceptions.

4. On the other hand, skips are distinctly faulty

a. After any tone which is obviously inharmonic or dissonant, i.e., foreign to the prevailing chord.

To this rule there are two important exceptions:

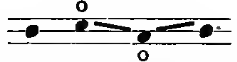

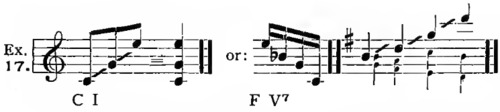

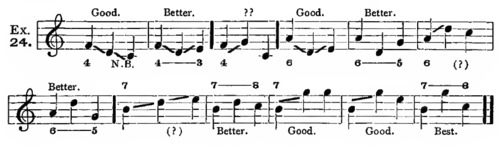

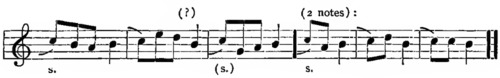

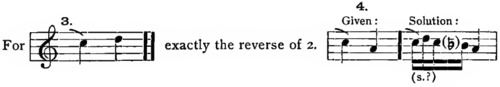

(1) It is always possible to leap a 3rd, from a neighboring-note to the opposite neighboring-note (of the same essential tone); usually, the essential tone follows and concludes the group,—as it also begins it:

That is to say. the figures  and

and  are always correct, in any reasonable movement (fast or slow), at any point in the measure, and whether the harmony remains the same, or is changed, during the group. The figure contains a “Double appoggiatura,” and results from inserting the upper and lower neighboring-tones successively between the principal tone and its recurrence.

are always correct, in any reasonable movement (fast or slow), at any point in the measure, and whether the harmony remains the same, or is changed, during the group. The figure contains a “Double appoggiatura,” and results from inserting the upper and lower neighboring-tones successively between the principal tone and its recurrence.

[ed. note: his “Double appoggiatura” is sometimes called a cambiata figure or a neighbor group (Kennan, Counterpoint, 3rd. ed., pp. 39–40), or a double-neighbor (Mark DeVoto, The New Harvard Dictionary of Music, ed. by Don Randel, s.v. “Counterpoint.”]

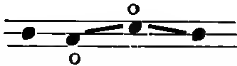

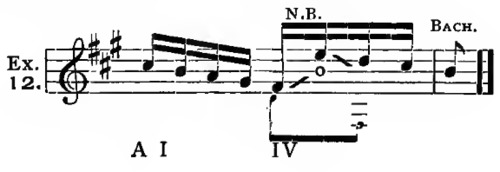

Not infrequently, especially in 3-tone groups, the recurrence of the principal tone is dispensed with. The license then consists in leaping down a 3rd from the upper neighboring-note; it is rarely applied in the opposite direction (leaping upward a 3rd from the lower neighbor). This is called the “unresolved upper neighboring-note.” [ed. note a.k.a. “incomplete neighbor tone”] For example:

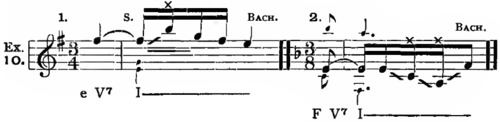

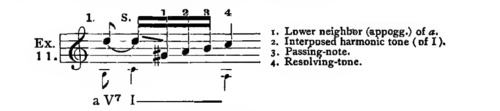

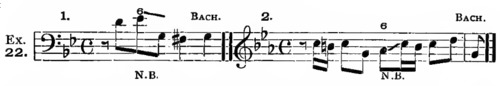

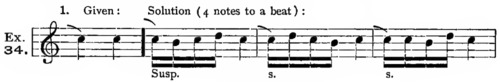

(2) It is possible to make an indirect or “ornamental” resolution of a Suspension, and of similar dissonant tones. Thus:

The interposed tones (marked x x), inserted between the Suspension and its resolving-tone, usually belong to the resolving-chord, as seen in the above illustrations; but brief diatonic passing-notes may be added. Thus:

[Two-Part Invention No. 3 in D major, BWV 774, mm. 54–56]

b. A skip, narrow or wide, to any inharmonic or dissonant tone (whereby the latter is deprived of its legitimate “preparation”), is, as a very general rule, objectionable. But it is by no means unpermissible, especially in the lighter (freer) styles of polyphony. See the g♯. in the preceding illustration; and the following:

c. The leap of an augmented 4th is usually, for one reason or another, very objectionable; and the progression by an augmented 2nd, diminished 3rd, major 7th, augmented 5th or 6th, or other awkward intervals, should be avoided. They are best justified (1) by chord-repetition (par. 3a):

[Fugue No. 1, BWV 846, from WTC Book I, mm. 19–20]

[13-2: Two-Part Invention No. 4 in D minor, BWV 775, mm. 1–2]

[13-3: Two-Part Invention No. 9 in F minor, BWV 780, m. 31]

or (2) by sequence-formation (par. 3c):

[Two-Part Invention No. 7 in E minor, BWV 778, m. 16]

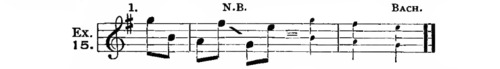

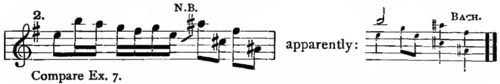

or (3) when occasioned by such distribution of the tones as represents the alternate appearance of two adjacent parts (correct in their respective movements):

[15-1: Two-Part Invention No. 7 in E minor, BWV 778, m. 14–15]

[15-2: Two-Part Invention No. 7 in E minor, BWV 778, m. 12]

or (4), as shown in par. 3d, by occurring at (after) an accented tone,—especially when the latter is the Tonic:

[Fugue No. 18 in G♯ minor, BWV 863, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

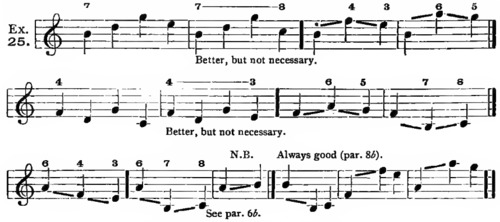

5. After a wide leap (beyond a 3rd) the part should turn, and progress in the opposite direction. See Exs. 6a, [ex.] 7, [ex.] 8, [ex.] 12, [ex.] 13. To this very important and general rule there are a few exceptions, as follows:

a. The part may continue in the same direction after a skip, if it passes on into a tone which belongs to the same chord, whether the harmony changes meanwhile, or not. Thus:

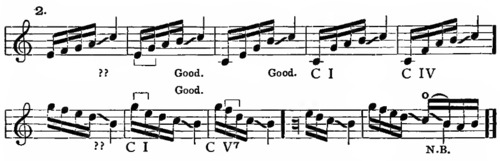

(Correct in either direction.)

The following successive skips are all very doubtful, because their aggregate effect is not harmonious:

(Doubtful, in either direction, because these are not legitimate chord-forms.)

Compare par. 3a.

b. It is almost always correct to pass on diatonically in the same direction, after a wide leap, if the direction of the part is then changed; i.e., it is usually sufficient to change the direction at the second tone after the leap. For example:

[Fugue No. 18 in G♯ minor, BWV 863, from WTC Book I, mm. 17–18]

In this example the whole structure suggests a distribution of the tones of two adjacent parts (noted in Ex. 15), equivalent to:

[Fugue No. 18 in G♯ minor, BWV 863, from WTC Book I, mm. 17–18]

Besides, the formation is sequential (par. 3c).

c. The part need not turn, after a wide leap, if it remains, even briefly, upon the same tone; — whether the latter be reiterated,

or simply held, for a pulse equivalent to repetition,

or embellished by either neighboring-tone:

[Fugue No. 21 in B♭ major, BWV 866, from WTC Book I, mm. 2–3, 5–6

Active Tones.

6. The natural or inherent tendencies of certain scale-steps (called Active steps because of their strong natural inclination to move) are as follows:

That of the 7th scale-step (Leading-tone) is to ascend diatonically; that of the 6th scale-step to descend diatonically; and that of the 4th scale-step to descend diatonically.

Besides these, there are a number of acquired tendencies, as follows (all diatonic):

That of all chord-sevenths, chord-ninths, and diminished 5ths and 7ths to descend; that of all raised (altered) scale-steps to ascend; that of all lowered scale-steps to descend; and that of Suspensions to pass into their respective resolving-tones.

Rule. — These natural and acquired tendencies should be respected, as far as is consistent with reasonable freedom of melodic movement.

For illustration of the natural tendencies (these being the most significant in the conduct of single melodic parts):

[21-1: Fugue No. 7 in E♭ major, BWV 876, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–3]

[21-2: Fugue No. 20 in A minor, BWV 865, from WTC Book I, m. 1]

See also Ex. 1; Ex. 6a, Nos. 1 and 3.

As indicated, the regular resolution of all active tones is effected diatonically (i.e., stepwise). To the above rule there may be, both as concerns direction and distance, the following

Exceptions.

a. An active tone may leap to any tone that belongs (or might belong) to the same chord; compare par. 3a. The leap may be made either upward or downward, though always best in the proper direction (that corresponding to the resolution). Thus:

[22-1: Fugue No. 16 in G minor, BWV 861, from WTC Book I, m. 1]

[22-2: Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 847, from WTC Book I, m. 1–2]

[22-3: Fugue No. 5 in D major, BWV 874, from WTC Book II, m. 1–2]

[22-4: Fugue No. 15 in G major, BWV 884 from WTC Book II, mm. 2–4]

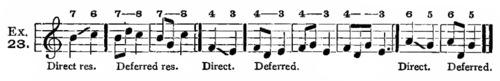

Such disjunct movements from the active tones constitute, often, examples of the indirect (or “deferred”) resolution, referred to in par. 4a, (2). That is, the unexpected tone or tones are simply interposed between the active tone and its resolution. Thus:

As a rule, if only one tone of the same chord intervenes, the obligation remains, and the resolving-tone should follow; though this depends largely upon whether the interposed tone lies in the direction of the resolution or not, — if the active tone progresses in the proper direction, its obligation is at least partly canceled. For illustration:

If two tones of the same chord follow the active tone, its resolution may be evaded; or if the active tone passes to another active tone, the resolution of the latter is sufficient. Thus:

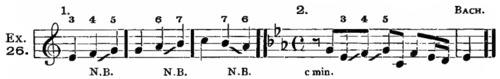

b. The natural tendency of these active scale-steps may be counteracted by approaching them stepwise in the corresponding direction (i.e., that in opposition to their tendency); in which case they may continue in the (false) direction, along the scale.

[26-2: Fugue No. 2 in C minor, BWV 871, from WTC Book II, m. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 23 in B major, BWV 868, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 13 in F♯ major, BWV 858 from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 875, from WTC Book II, m. 1–2]

N.B. — This is merely an obvious corroboration of par. 1, in its broadest application.

c. An active scale-step, when approached thus in the “opposite” direction, has the option either of passing onward (as in Ex. 26), or of turning and fulfilling its natural obligation. But, if approached in the direction corresponding to its tendency, it is very difficult indeed for the active tone to turn and progress incorrectly. The most natural exception (possibly the only defensible one) is when mere melodic embellishment, or deferred resolution, is involved, — i.e., when one of the tones is a neighboring-note, or obviously an interposed tone. For example:

[Fugue No. 1 in C major, BWV 870 from WTC Book II, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 13 in F♯ major, BWV 858 from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 21 in B♭ major, BWV 866, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–3]

[Fugue No. 17 in A♭ major, BWV 862, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 11 in F major, BWV 856, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

*1) The 4th scale-step is here evidently an auxiliary (embellishing) tone; and f♮ is taken, in preference to f♯, because of the prevailing C-major key.

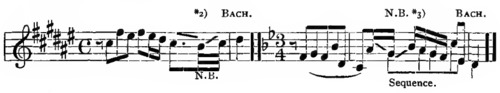

*2) Same as note *1).

*3) An embellishment of the Leading-tone a, as in Ex. 9a, neatly conducted into a sequence of the preceding figure.

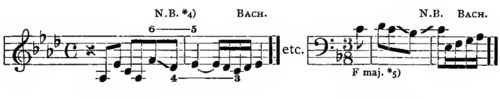

*4) A deferred resolution of both the 6th and 4th steps.

*5) Like note *1); b♭ is taken, instead of b♮, to prevent the impression of C major.

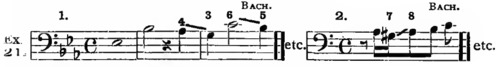

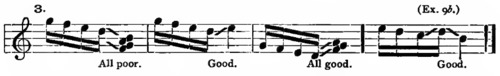

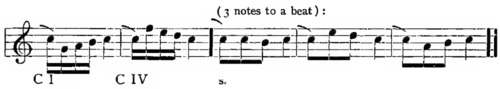

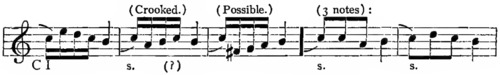

7. Care must be taken to avoid any awkward conditions at the transition from one beat into the next. In approaching an accented fraction of the (following) beat, with a fairly rapid figure, the latter must be so calculated as to reach the desired point at precisely the right moment, — not too soon (so that awkward anticipation results), nor too late (so that an equally awkward leap is necessary). Supposing c to be the tone to be reached, in a rhythm of four tones to the (preceding) beat:

In measure 1 the run is faulty because it reaches the c too soon; in measure 2 it is calculated to reach c too late; measure 3 is correct.

As a rule, after moving stepwise toward the desired tone (at the beginning of the next beat), it is necessary to continue and enter the new beat stepwise, — not with a leap. If a leap be necessary, it should be made earlier in the figure, according to the prevailing harmonic conditions:

In the last measure, the awkward leap into b is avoided by inserting an accented passing-note; this is a very common and excellent device.

While it is usually better to continue thus, and enter the next beat diatonically in the same direction, there is no objection to turning at the transitional point:

8. The reiteration of a tone should be avoided in rapid rhythmic succession. It is, however, entirely permissible in slow movement; i.e., after a tone of full-beat value or more, — more rarely after one of half-beat value; always good after a tie.

[29-2: Fugue No. 5 in D major, BWV 874, from WTC Book II, m. 1]

[29-3 Fugue No. 12 in F minor, BWV 881 from WTC Book II, mm. 1]

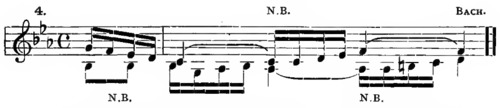

[Prelude No. 7 in E♭ major, BWV 852, from WTC Book I, mm. 50–51]

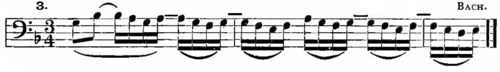

a. Rapid reiterations are justified when occurring several times in succession, especially in sequences:

[30-1: Fugue No. 13 in F♯ major, BWV 858 from WTC Book I, m. 7]

[30-2: Fugue No. 21 in B♭ major, BWV 890, from WTC Book II, mm. 40–44]

[30-3: Fugue No. 6 in D minor, BWV 851, from WTC Book I, m. 9–11]

b. The most natural remedy, in case of objectionable reiterations, is to leap up or down an octave, — always an effective and permissible progression:

9. The tie is one of the most effective devices for obtaining the desirable rhythmic independence of the several parts; it serves to procure time-values of an extent — and at locations — not provided for by the ordinary characters of notation. The tie extends the duration of a tone from one beat into the next, or, with still more striking effect, from the last beat or beats of one metric group into the first beat of the following group (i.e., at, or over into, the accented pulses).

a. A long tie — from a long or heavy note, of at least a whole (or possibly half) beat value — is everywhere possible.

b. On the contrary, a short tie — as a rule, from any value less than a half-beat of the prevailing meter, in moderate tempo, — should be avoided.

Both of these rules coincide, in rhythmic principle, with par. 8.

c. As a general rule, the second tone (the one into which the tie extends) should not be of longer duration than that of the first (preceding) tone.

d. A brief tie, from a tone of less than half-beat duration (see b), is best justified when it gives rise to a Suspension:

[Prelude No. 12 in F minor, BWV 857 from WTC Book I, m. 12]

or when several such (brief) ties occur in succession, as syncopated form of an entire passage:

[Fugue No. 23 in B major, BWV 868, from WTC Book I, mm. 22–23]

[Fugue No. 4 in C♯ minor, BWV 873, from WTC Book II, m. 34–35]

e. After a tie of fairly long duration, the part may progress either quickly or deliberately; if the tie is brief, however, the part should progress with corresponding promptness, as indicated at c.

f. A tie may be followed:

- by the same tone (reiteration, par. 8);

- by the next higher or next lower tone (which progression provides for any “resolution” that may be necessary, — for example, in case of a Suspension);

- by the tone a 3rd above or below, either as harmonic skip, involving no further obligation, or as opposite neighboring-note of the resolving-tone, in case such be necessary. See par. 4a (1);

- or by any still more remote tone, belonging to the momentary chord, — again either as harmonic skip, or as interposed tone before resolution. See par. 4a (2).

The choice of these possible, and equally good, progressions depends principally (often solely) upon the location of the essential tone required or desired at the beginning of the next beat, and is governed in any case by the rules of par. 7, which see.

Given the tied note c, followed in the next beat by c:

10. Brief rests ( ) may be inserted at the beginning (generally only at the beginning) of almost any beat, but especially any accented beat. The rest should not occur, as a rule, after any inharmonic tone (on account of the resolution); nor after any very short tone, — occupying the last unaccented fraction of the preceding beat; nor in the course of a beat, in such a manner as to impair the rhythm:

) may be inserted at the beginning (generally only at the beginning) of almost any beat, but especially any accented beat. The rest should not occur, as a rule, after any inharmonic tone (on account of the resolution); nor after any very short tone, — occupying the last unaccented fraction of the preceding beat; nor in the course of a beat, in such a manner as to impair the rhythm:

Longer rests ( ,

,  , etc.) are good almost anywhere, but under precisely the same limitations:

, etc.) are good almost anywhere, but under precisely the same limitations:

[Fugue No. 7 in E♭ major, BWV 852, from WTC Book I, mm. 23–24]

[Fugue No. 12 in F minor, BWV 857 from WTC Book I, mm. 13–14]

See also Ex. 37, No. 2.

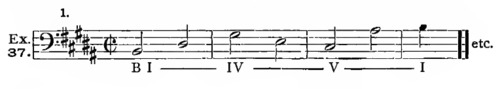

11. The influence of harmonic laws upon the conduct of each single part (even when isolated, — temporarily unattended by other parts), is obvious from many passages in the foregoing rules; especially par. 3a, [par.] 4, 5a, 6a, 9f. The next chapter will demonstrate in detail the manifest necessity of basing the polyphonic complex upon a harmonic fundament, and of regarding the polyphonic style simply as an advanced stage in the manipulation of the self-same original factors of Harmony, — characterized by that superior freedom and independence which advanced growth brings. But, aside from the controlling influence exerted by harmonic law upon the co-operation of two or more simultaneous parts, the same influence is present even in the conception and movements of the single, unaccompanied part; for example, the direct derivation of a melody from a harmonic source, or its dictation by a harmonic purpose, is plainly shown in such motives as the following (all from Bach):

[Fugue No. 23 in B major, BWV 892, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–4]

[37-2: Fugue No. 20 in A minor, BWV 889, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–3]

[37-3: Fugue No. 17 in A♭ major, BWV 862, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Fugue No. 18 in G♯ minor, BWV 887, from WTC Book II, mm. 1–5]

See also Exs. 5, [ex.] 7, [ex.] 14, [ex.] 15, [ex.] 22, Ex. 30-1, etc.

Such evidences of harmonic design are most palpable in melodies in disjunct movement (i.e., with many skips); but are more vague in melodies in preponderantly conjunct movement. Hence it is that, according to the rule of par. 1, conjunct or stepwise progression is a characteristic distinction of the polyphonic style of composition, in which the parts are more emancipated from the governing power of harmonic bodies; the homophonic style, in which this power constantly prevails, being distinguished, on the contrary, by greater frequency of skips, and disjunct movement generally.

12a. The above rules apply, with no essential modifications, to the minor as well as the major mode. The only noteworthy addition is, that in the ascending scale-progression in minor the 6th step (as defined by the signature) is generally raised; and in the descending scale-progression, the 7th step is generally lowered. See par. 20.

b. Further, all of the given rules are most binding in prominent parts, namely, the uppermost and lowermost of the polyphonic complex; but are subject to a certain degree of license in the inner part or parts.

c. All reasonable violations of the rules are palliated (and even completely justified) by “thematic authority,” — that is, when called forth by deference to, or confirmation of, any perfectly apparent and recognizable thematic design, involved by the Imitation of a motive or figure (par. 24), by the Sequence (par. 3c), or any other sufficiently obvious and plausible melodic purpose.

Summary.

13a. Conjunct movement is almost invariably good.

Principal exception, Ex. 27, measures 1–3.

b. Skips are good between chord-tones, and justifiable by correct harmonic conditions.

Principal exceptions, Ex. 6b, par. 4a, 4c.

c. Any essential (harmonic) tone may be preceded by its two (upper and lower) neighbors. Par. 4a, (1).

d. After a wide skip, the part turns, either immediately or at the second next tone.

Principal exception, par. 5a.

e. Any progressions are possible which represent the successive (or alternate) distribution, in one part, of tones which would constitute two (or possibly more) strictly regular adjacent parts.

f. The tendency of active tones should be respected, and all “resolutions” properly effected.

Principal exceptions, par. 6a and [par.] 6b.

g. The direction of comparatively rapid figures must be governed by the essential tone (or first tone) of the. following beat. Par. 7.

h. The movements of a melodic part must corroborate some rational harmonic purpose; especially applicable to disjunct movement. Par. 11.

i. Cause for almost any irregularity is afforded by the Sequence, or any other entirely obvious and defensible thematic purpose. Par. 3c, Ex. 14. Ex. 30; Par. 12c.

EXERCISE 1.

A. Analyze, thoroughly and minutely, the progressions of the solo part at the beginning of every Fugue in the Well-tempered Clavichord of J. S. Bach, for about 5 or 6 measures (even after another part may have joined the first). Every movement, from tone to tone, and the collective relations from measure to measure, are to be tested and demonstrated with reference to the above rules.

B. Write a large number of original melodic sentences (40 or 50), of from one to three or four measures in length, illustrating each rule and exception given in Chapter I., successively. Terminate each sentence upon the first unit of the final measure; employ every variety of measure (from  to

to  ), and all the keys, major and minor alternately. Imitate the rhythm and style of the Bach models.

), and all the keys, major and minor alternately. Imitate the rhythm and style of the Bach models.