CHAPTER III.

Condition 3: “Individuality of Parts.”

The Rhythmic Relation of One Part to Another.

22. The fundamental rule is, diversity and contrast between the rhythms of the separate parts. But the collective effect of the rhythm of two associated contrapuntal parts is generally that of uniform movement.

a. A certain grade of tone-values is adopted as the uniform basis of motion (most commonly the 8th- or 16th-note, sometimes as triplet), and this fundamental rate is sustained with predominating regularity. It is rarely pursued in either part alone, or in both parts at once, for many successive beats; but alternates more or less regularly between the parts,—the part not conducting the fundamental rhythm relaxing, meanwhile, to tone-values of any reasonable length.

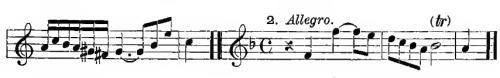

Distinction in rhythmic formation must be regarded as the most powerful means of realizing the necessary independence and individuality of the several parts of a polyphonic complex. Hence, the fundamental law of Contrasting Rhythm, and Alternation. Similar rhythm in both parts at once (as in Ex. 46), or persistent uniform rhythm in either part (as in the examples made in Exercise 3, etc.), militates against this vital principle of rhythmic individuality, and must be used sparingly, as an exception to the rule. For example (correct rhythm):

[Two-Part Invention no. 1 in C major, BWV 772, mm. 15–16]

See, further, Ex. 44-2 (16th-triplets at first in lower, and then in upper part). Ex. 52-1, — the rhythm of 16th-notes in alternating parts during two measures; then maintained for a time in upper part alone. — Ex. 52-2, similar. — Ex. 55-3.

In Ex. 46 the fundamental rhythm is maintained in both parts at once; in Ex. 53-2, it is uniform in each part for some time; both cases are somewhat exceptional, as already stated. In Ex. 54-1, the upper part is uniform, but the lower one diversified.

b. Modifications of the fundamental rate of motion, for the sake of variety, in either or both of the parts, conform usually to the laws of regular rhythm; i.e., comparatively heavy (long) tones should occupy the heavier beats, and lighter (short) tones the light beats. In other words, relaxation to longer tone-values should generally occur at accented pulses, and acceleration to shorter tone-values at unaccented pulses.

See Ex. 44, No. 1 (lower part, 16th-notes on beats 2–3, 5–6; the 8th-notes on accented beats 1 and 4). Ex. 44, No. 1, the change of rhythm from 16ths to 8ths takes place at the accented unit (lower part). Ex. 45, No. 1, heaviest note at beginning of measure. Ex. 45-2, fundamental rhythm of 8th-notes, accelerated to 16ths on unaccented fractions of 2nd and 4th beats. Ex. 57-3, fundamental rhythms of 16th-notes, accelerated to 32nds on unaccented fractions.

c. Still, as long as either one of the two parts is conducted in uniform rhythm, it appears easy to justify irregularities of rhythm in the other part.

See Ex. 44, No. 6; the upper part is practically uniform (8ths), while the lower, near the end, is distinctly irregular. Ex. 47, lower part uniform 16ths, upper part irregular. Ex. 52-3, lower part uniform, upper part irregular. Ex. 52-5 similar. Ex. 54-1, and 3. Ex. 57-5, end of measure 1. Ex. 40, B.

d. The importance of the tie must here again be emphasized. By no other means can an equally effective and legitimate result be obtained, as tending toward the mutual independence of the parts. All forms of syncopation are simply the consequence of ties (actual, or—according to their location in the measure — implied), and therefore serve the same important end. The treatment of the tie is defined in par. 9, which review.

An especially felicitous illustration of the tie is given in Ex. 44, No. 11. See also Ex. 45-2. Ex. 50-1 (syncopation). In each of these cases the general rhythmic effect is regular, and preponderantly uniform, because of the correct alternation of the parts, as shown in par. 22a. Ex. 64-3 (syncopation).

The absence of ties will be observed most frequently in two-part counterpoint of a somewhat lively character and movement, where but little opportunity is afforded for the check which ties naturally occasion (comp. par. 9b). See Ex. 47; Ex. 52-1, 52-2, 52-4.

Of barely less importance is the occasional rest, which, in the proper place, and in judicious proportion, is quite as valuable as any tone, often far more so. See par. 10. Its use is exemplified in Ex. 63; Ex. 64, No. 2; Ex. 91.

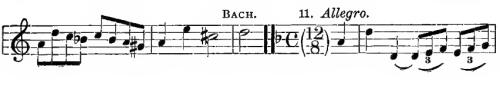

e. Distinctly irregular rhythmic formations are justified by sequences, or any other form of symmetrical successive recurrence; comp. par. 21f. For example:

[Prelude No. 20 in A minor, BWV 865, from WTC Book I, mm. 1–2]

[Prelude No. 10 in E minor, BWV 879, from WTC Book II, mm. 3–4]

[Two-Part Invention no. 6 in E major, BWV 777, mm. 1–3]

*1) The rhythmic irregularities here are: the division of the first (accented) beat into 16ths, while the 2nd and 3rd beats remain undivided; and the division of the entire second group of 8ths, while the (less weighty) third group remains undivided. The self-same irregularities, however, are repeated, and thereby balanced, in the following measure.

*2) The irregularities of the first measure are reproduced in the next.

*3) The syncopation of the upper part is continued, symmetrically, for three measures. See also Ex. 6A-3, measures 2 and 3, uniformly irregular; Ex. 54-3 (the irregular division of the first beat is sufficiently, if not totally, balanced by similar treatment of the next accent, — 3rd beat). See also Bach, W.-t. Cl., Vol. I, Prelude 13, measures 2–4; Vol. II, Prelude 13, measures 1, 2.

EXERCISE 6.

A. Analyze Bach, Two-voice Invention, No. 7, chiefly with reference to the rhythmic treatment of the two parts. Also, Two-voice Invention, No. 1. Also, Well-tempered Clav., Vol. II, Prelude 8, measures 1–5; Prelude 10, measures 23–48.

B. Add a second part (above and below, as before) to each of the following melodic motives or sentences. Refer, constantly, to pars. 7; [par] 9 (particularly [par 9]a, [par 9]b, [par 9]f, Ex. 34); [par] 10; 17b and [17]f; the summaries, pars. 13, [par] 21; and par. 22.

N. B. Perhaps the most helpful and important rule is, to look constantly forward, mentally defining the tone necessary or desirable at the next accent, and guiding the added part accordingly.

1) The added part may begin, in each case, exactly with the given one; but it is better that it do so a little after, or before, the latter. Further, the student should make several different versions of each task.

2) After having concluded his own experiments with these last melodic extracts from 2-voice polyphonic passages of Bach, the student may compare them with the respective original versions; No. 9 occurs in the 2nd French Suite, “Air,” measures 1–4; No. 10, in the Art of Fugue, Fugue 9, measures 8–17; No. 11, in the same, Fugue 13, measures 5–9; No. 12, in the 9th Two-voice Invention, measures 17–29; No. 13, clavichord-fugue on “B-a-c-h” measures 5–8.

3) In earlier methods of notation, this figure  represented the modern

represented the modern  whenever employed in connection with triplets (as here).

whenever employed in connection with triplets (as here).