CHAPTER V.

The Two-Voice Invention.

39. An Invention may be constructed, like any homophonic composition, according to the design of the so-called Part-forms, or Song-forms. But it is somewhat inconsistent with the polyphonic style to check the current of thematic development with the emphasis necessary for the Cadence of a genuine and well-defined Part;[*] and it is, therefore, more common for the structural design of Inventions to consist in a kind of group-form, or chain-form, the several divisions of which may most appropriately be called “Sections.”

a. The Section of polyphonic designs differs from the Part of homophonic forms in being, as a rule, less regular and definite in character; in terminating with a brief, and less distinct, form of cadence; and in maintaining less obvious formative relation (with regard to general melodic design) to its fellow-divisions. For these reasons, the number of Sections, also, is entirely optional.

b. Generally, each successive Section undertakes a somewhat different method of manipulation, or the development of some special resource of the Motive. But, notwithstanding the comparative independence thus effected, it is necessary to preserve a certain measure of logical connection and relation between the Sections, and therefore it is customary to revert, from time to time, to some structural feature of an earlier Section; thus the idea, at least, of the Homophonic designs[*] prevails in the polyphonic designs as well — especially in the Invention, which, in contents and purpose, is more closely akin to the ordinary (homophonic) Song-forms than are the more advanced grades of polyphony.

The First Section.

40. The 1st Section, or “Exposition,” of the Invention, will exhibit, as a rule, all of the structural factors enumerated in par. 38.

a. The Motive may be first announced by either the upper or (more rarely) the lower of the two parts; generally it appears alone, though it is sometimes accompanied by a few unimportant auxiliary tones, the better to establish chord, key and rhythm.

Compare Bach, 2-voice Inventions, Nos. 1, 3, 4, 8, with Nos. 7, 13 — the first measures of each.

b. The first Imitation, in an Invention, is almost always made in the octave; though occasionally the fifth is chosen, or some other interval which adjusts itself readily to the harmonic design, — any interval being permissible.

In Bach, 2-voice Inventions, Nos. 1, 3, 4, 7, 8, and 13, the first Imitation is in the lower 8ve; in No. 10 it is in the 5th; in Bach, English Suite No. 6, 2nd movement of the “Prélude,” it is in the 4th; the same in Bach, Partita II, 3rd movement of the “Sinfonia” (3-4 time).

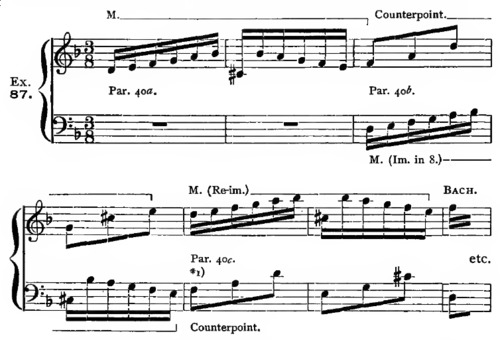

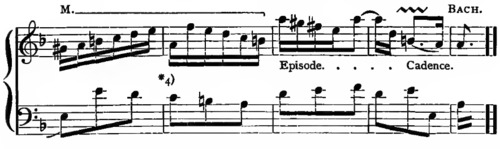

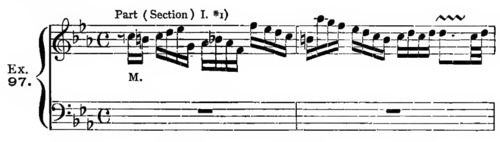

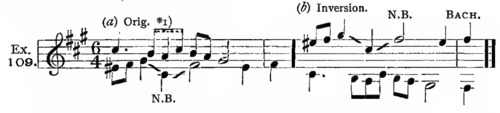

c. The details of the Exposition up to this point have been thoroughly exemplified in the work of Exercise 7, etc. The next step in the development of the thematic design is, usually, another immediate recurrence of the motive, in the first (i.e., leading) part, as re-imitation of the preceding announcement. The interval of this new Imitation is optional, though 8ve or 5th is the most usual. Meanwhile the other (second) part continues its movement, as contrapuntal associate of the Motive, according to par. 35. See, also, par. 41a. For example:

*1) This “Counterpoint” to the second recurrence of the Motive closely resembles the first contrapuntal associate (measures 3–4). It is so natural and tempting to adhere thus to the first Counterpoint, that the student must be reminded of the monotony it involves, and be warned against making it a rule. The recurrences of the Motive provide amply for the necessary condition of consistency and symmetry; the equally necessary condition of variety devolves largely upon the contrapuntal associates, which may assume more or less different forms at the successive recurrences of the Motive. On the other hand, to guard against excess in this respect, it is advisable to adhere to a certain counter-motive during two (or three) consecutive announcements of the Motive, and to return, from time to time, in the following Sections, to such former Counter-motives (i.e., “counterpoints”).

See further: Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 1, first six beats; the second recurrence of the Motive (meas. 2) is a Re-imitation in the 5th. The same is the case in No. 7, first six beats (Ex. 91). In No. 8, measures 1–3, it is in the 3rd.

d. What follows, after this second recurrence (i.e., the third announcement) of the Motive, cannot be determined in detail, but only with reference to the general purpose of the entire first Section, which involves the following contents: —

- The announcement of the Motive;

- The Imitation and successive recurrence, as necessary thematic basis;

- The exhibition of variety (episodic and otherwise);

- A modulation into the key in which the Section is to terminate;

- The establishing of this key; and

- A palpable Cadence in the same.

e. Perhaps the most imperative condition, at the juncture reached in the above example, is that of variety. This may be obtained, (1) by substituting the principle of the Sequence for that of Imitation, — i.e., reproducing the Motive once or twice in the same part instead of the opposite part; or (2) by dropping the thematic thread, and proceeding episodically.

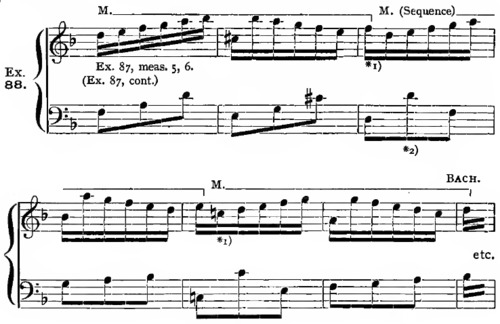

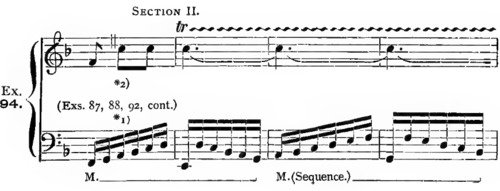

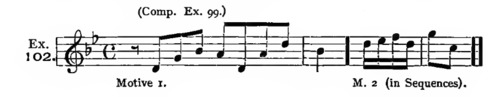

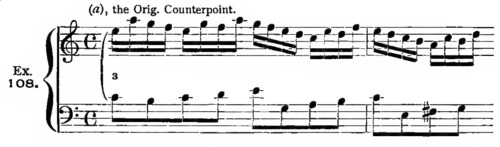

The first alternative, the Sequence (see par. 41c), is illustrated in the following:

*1) The Motive, instead of being again imitated in the other part, reappears as Sequence in the same part, upon the next lower step. The first tone is omitted, in order not to disturb the smooth termination of the preceding announcement. A clue to the impulses which led Bach to choose this particular interval of Sequence, will be found in par. 41a. See also par. 40g.

*2) This “Counterpoint” differs from the preceding ones. Review Ex. 87, Note *1). It is retained during the following Sequence.

See also Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, first 11 measures of Prelude 10; — Motive of 2 measures, accompanied briefly by auxiliary tones; followed by imitation in the 8ve; then a re-imitation, again in the 8ve; then a Sequence, a third above, — the “Counterpoints” constantly differing, up to this point; then another Sequence, a third above, — the “Counterpoint” as before, but in a lower octave.

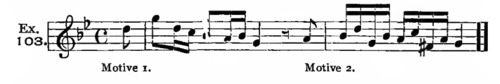

The second alternative, the Episode (see par. 38d), is illustrated in the following:

*1) In the original (French Suite No. 5, “Courante”), a number of auxiliary tones accompany the first announcement of the Motive; they are omitted here.

*2) The “Episode” is interpolated already after the first Imitation; it is derived from the Counter-motive in the upper part (2nd measure), which is retained (or imitated) in the lower part in a somewhat modified form, and accompanied by a new contrapuntal figure in the upper part.

Examine, also, Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 10, first 6 measures, and endeavor to trace the derivation of the episodical passage; Bach, English Suites, No. 1, “Bourree I,” meas. 1–8; English Suites, No. 2, “Prelude,” meas. 1–4; English Suites, No. 4, “Prelude,” meas. 1–6. Further: [from Fantasie BWV 919]

*1) This counterpoint, at the 2nd recurrence of the Motive, corresponds exactly to the Counter-motive of the first Imitation (meas. 2).

*2) The derivation of this episodic passage is not as obvious as in some examples, but nevertheless palpably in close keeping with the preceding thematic portions. The figure marked a may be accounted for in two ways, as shown by the two slurs: either as part of the Counter-motive, in contrary motion, or (the lower slur) as imitation of the ending of the Motive; b bears close general resemblance to the Motive, though the indicated derivation may appear tortuous; it embraces three beats, and is reproduced in slightly modified Sequence; d is derived from a; its modified Sequence, e, is admirably utilized in launching the next recurrence of the Motive. See par. 41b.

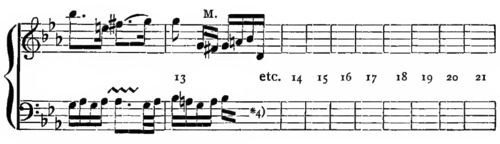

f. On the other hand, these specific modes of obtaining variety are sometimes not resorted to until the alternating Imitations have been extended still farther. For illustration:

*1) Auxiliary tones (par. 40a).

*2) Up to this point, the development is not only exclusively thematic but consists in the unrelieved alternate Imitation of the Motive. This must be regarded as very exceptional, and illustrates how, even in the polyphonic style, the determination to realize a clear structural design may sometimes overrule the more specific thematic conditions of the texture; it is the prevalence of “form” over “thematic development.” The counterpoint is uniform in the lower part, but is diversified in the upper part at each successive Imitation, excepting the last one. What follows, as Episode, is easily demonstrated.

*3) The conduct of the lower part effectively illustrates the application of the brief rest (par. 10, which review).

See par. 22d, last clause; Ex. 90, meas. 4 and 6.

See also, Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 8, meas. 1–5 (four announcements of the Motive before the texture becomes episodic).

In No. 1 of the 2-voice Inventions, the Motive is announced five times (the 5th time in Contrary motion) before the alternative of the “Sequence” is adopted; and no less than ten consecutive announcements are made before an “Episode” is. introduced.

Further, Bach, 4th French Suite, “Gavotte,” meas. 1–3.

g. The modulatory design of the First Section of an Invention corresponds to that of the First Part in homophonic forms, namely: if in major, the Section generally terminates in its Dominant key; if in minor, usually in its Relative (major) key. Exceptionally, these relations may be exchanged (i.e., the Dominant key from minor, and the Relative key from major). Or some other next-related key may be chosen; especially the Relative of the Dominant, — rarely the Sub-dominant keys.

The influence of this modulatory purpose will probably be evinced as soon as the original key is sufficiently established; generally during the first or second episodic passage; or during a line of sequential announcements of the motive.

In Ex. 88, the latter is clearly illustrated; in measures 78 (of the entire Invention) the lines of d minor waver, and in measures 9–10 the transition into F major is complete. In Ex. 91, precisely the same course is pursued: measures 1–3 are in e minor, measures 4–5 in G major. See also Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 1; measures 1–3 in C major; during the following sequences of the Motive (in contrary motion) in the upper part, the digression into G major is initiated, and is confirmed in the following (5th) measure.

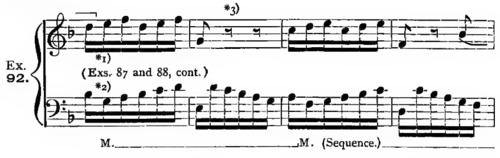

And the remainder of the Section consists, probably, in a comparatively brief confirmation of the new key, and a cadence in the latter. For example:

*1) This example must be studied in connection with Exs. 87 and [ex.] 88. The “Counterpoint,” here, differs from the preceding ones; it is retained for the next announcement, and then, again, new forms are invented. Review Ex. 87, Note *1).

*2) This announcement of the Motive is an Imitation of the last Sequence in the upper part (Ex. 88); it is followed by a similar line of Sequences, but not in regular interval-succession, as before.

*3) Compare Ex. 91, Note *3).

*4) The “cadence-formula.” See par. 40h.

*5) See also Ex. 93, No. 2, end.

When the Section is extended to an unusual length, the corresponding breadth of design will probably induce (or necessitate) transient modulations into various next-related keys; and the prescribed modulatory aim of the whole may not assert itself until the Section approaches its cadence. In this case, further, the cadence is apt to be proportionately stronger.

See Bach, Well-tempered Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 10, first twenty or thirty measures; — to be analyzed solely with reference to the changes of key.

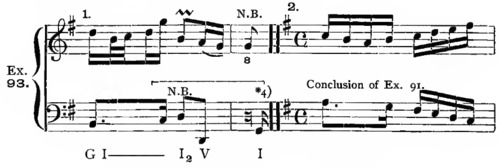

h. The Cadences of polyphonic Sections are generally, as implied in par. 39a, much less decisive than those of homophonic forms, both in harmonic and rhythmic respect. Still, they assume the aspect of the Perfect cadence (only excepting a few rare instances where the formal purpose demands the effect of a Semi-cadence), and, therefore, the distinctive traits of the former are usually preserved, — especially as concerns the lower part (the Bass).*

But the rhythmic interruption (or pause) is brief; so much so as to create the impression of an Elision;** for the thematic thread is taken up so promptly that the cadence-group of one Section is, almost always, at the same time the initial group of the next.

For illustration (from Bach):

* “Homophonic Forms,” par. 3, par. 6. ** Idem, par. 60.

*1) This cadence is much less distinct than the preceding ones, because of the instability of the lower (Bass) part, and its culminating upon an Inversion of the Tonic harmony. But the weight of the upper part, resting for some time upon the Tonic note, is sufficient.

*2) Here, again, the lower part is hasty, though its final tones are strictly cadential.

*3) This cadence, on the contrary, is unusually strong, being the final cadence of the entire Invention. It is permissible thus to add auxiliary tones, at any cadence. In Nos. 3 and 5 the leaps in the upper part are equivalent to two distinct part-progressions (Exs. 15, [ex.] 19), and give to the cadence the strength of 3-part texture.

*4) The lower part proceeds immediately with the Motive.

The material of the cadence is very likely, in view of its special object, to be episodic, and may even be entirely independent of all anterior figures. It is, however, also possible, by ingenious treatment, to interweave thematic figures with the cadence, — especially when more than two parts are used.

See Bach, W.-t. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue I, measure 19; — cadence on 3rd beat, during thematic announcements (in Stretto) in Tenor and Alto. See also Ex. 96. Note *1). Ex. 116, last measure.

Additional General Principles.

41a. Influence of harmonic bent. In determining the progressive conduct of polyphonic parts, the harmonic and modulatory inclinations must be respected, and even anticipated.

If the harmonic progression (or, in other words, the choice of the next chord) is self-defining, or perhaps even imperative, — as, for instance, at certain urgent Dominant or Second-dominant chords, which demand resolution, — then this, the Harmony, will dictate the movement of the parts; and, if necessary, the unessential licences of Imitation (par. 28) will be summoned, to fit the thematic intention to this harmonic need.

Should the harmonic progression not be self-defining, but optional,— as, for instance, after any Tonic chord, — then the thematic design will supply the impulse and determine the choice of chord and key; and either the Motive, with or without unessential modification, or the Episode, will be chosen, as appears most convenient. Review par. 11, par. 18, and the last clause in the directions to Exercise 6B.

b. The Episodes. It would be very wrong to assume that the above episodic passages (Exs. 89, [ex]. 90, [ex.] 91) proceeded from a deliberate intention, on Bach’s part, to use just these particular fragments of thematic material, in just this manner. His purpose was a far broader one; and the episodes, while responding first of all to the demand for variety, are simply incidents in the realization of that purpose.

In general, then, the episode is rather an accidental consequence than an aim; and its details, — chosen, as they may be, from a myriad of equally consistent possibilities, — are influenced by the broad harmonic conditions noted in par. 41a, and determined by such comprehensive considerations of Form as those specified in par. 40d.

It is true, however, that the beginner must work along narrower lines, until his range of experience widens toward the master’s standard. And the student will therefore, for a time, plan his episodic passages as more or less mechanical derivations from foregoing thematic premises; making generous use of the Sequence (par. 41c); not pausing long to choose, but accepting the first reasonable suggestion; and meanwhile analyzing the methods of great polyphonic writers (as found in the given citations) with the most penetrating scrutiny,—thus enriching his experience both by experiment and by observation.

As already observed, the number and variety of episodic deductions from anterior thematic figures, is practically unlimited, and the difficulty lies, not in finding a derivative, but in choosing from among the well-nigh infinite range of possibilities. So that the student who is at first apprehensive of not knowing what to do, will soon experience the still more real embarrassment of deciding what not to do; and this latter consciousness is, in fact, the most trustworthy sign of progress in thematic musical thought. For among so many possible deductions, many grades of excellence will, of course, be represented; some episodic forms will be more appropriate, ingenious, and pregnant than others.

But, though the student may for awhile not succeed in finding the best forms, or even fairly good ones, the simple determination to adopt this deductive process, in his labors with the problem of musical composition, is, in itself, meritorious and wise. For such logical processes contribute invariably, at least in some degree, to the unity and stability of the musical structure. And as the student’s experience increases and his judgment matures, he will more and more readily and unerringly select the better and best forms. At all events, this dependence is vastly preferable to relying upon chance, or upon that most delusive of resources, personal inspiration, for the answer to the vital and constantly recurring question, “What next?” Eminent and indispensable as the impulse of emotional or intellectual ardor (“inspiration”) becomes to the advanced scholar and to the master of tone-texture, it is fraught with delusion and distraction to the beginner.

c. The Sequence. One of the most essential details of effective polyphony is the Sequence. It is the chief, if not the only efficient, safeguard against the most characteristic danger that besets the polyphonic style, — that of purposeless rambling, or the uncertain, discursive pursuit of a vague thematic scheme.

The Sequence imparts at least regularity and symmetry to the operations of thematic development; and, while particularly important in the more vagrant episodic components, is even freely used in the thematic passages themselves (par. 40e). Hence, the pupil may fall back upon Sequences at almost any time, and drift with them until some higher structural condition asserts itself. The number of Sequences should, however, be limited to two or three (i.e., three or four presentations of the figure at a time, in all). A larger number is permissible only when the figure is small. See also par. 21f.

d. Unusual species of Imitation, with Essential changes (par. 29, [par.] 31), are very rarely employed in the first Section, excepting the simplest variety of Shifted rhythm (par. 31c, second clause), and Contrary Motion; and even the latter should, as a rule, be deferred to the second, or a still later, Section. Both Augmentation and Diminution, excepting when applied to fragments of the Motive, are almost entirely inappropriate in the two-voice Invention. The Stretto is most valuable in the later course of a polyphonic form.

EXERCISE 11.

A. Analyze the following specimens of the First Section of the 2-voice Invention. The contents of each group or measure must be defined, either as Motive, Counterpoint, or Episode; and when the latter, every figure must be accounted for:

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 1, meas. 1–7.

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 8, meas. 1–12.

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 10, meas. 1–14.

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 3, meas. 1–12.

- Bach, Well-t. Clav., Vol. I., Prelude 14, meas. 1–12.

- Bach, English Suites, No. 4, “Prélude,” meas. 1–12.

- Bach, Partita (for clavichord), No. 2, “Sinfonia,” 3rd movement (3-4 time), meas. 1–20 (cadence in Dominant key).

- Bach, Partita No. 3, “Fantasia,” meas. 1–31 (largely episodic development of first half of Motive; cadence indefinite).

B. Take Motive No. 6 of Exercise 6B, and elaborate it into a moderately brief First Section, according to the above directions (par. 40, [par.] 41). Review par. 22a and [22]d.

N. B. Begin this, and each of the following examples, on a separate sheet, leaving ample space for the continuation dictated in Exercises 12 and 13.

- The same with Motive 6 of Exercise 7A.

- The same with Motive 5 of Exercise 6B.

- The same with Motive 4 of Exercise 6B.

- The same with Motive 3 of Exercise 7A.

- The same with Motive 4, or 11, or 2, of Exercise 7A.

C. The same with one major and one minor original Motive, — one measure, or a little more, in length, invented strictly according to par. 38a.

The Second Section.

42. The Second Section of an Invention must be conceived mainly as a continuation of the development of the Motive and its resources, initiated in the First Section. Its structural factors correspond to those of the latter (par. 38), but their arrangement is generally less systematic. The general requirements are as follows:

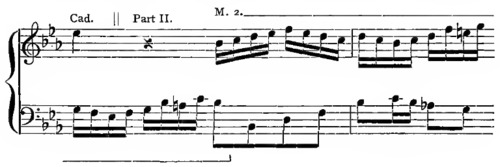

a. The new section may begin after the cadence of the foregoing has had its full rhythmic value, or it may follow immediately, after an elision. See par. 40h, second clause. It may begin with an announcement of the Motive (either alone, or with a contrapuntal associate); or with an episodic member. The former is the most natural and most common. Ex. 93, Note *4).

b. A certain degree of independence is desirable, and therefore the Second Section, while adhering to the spirit and general character of the First, may contain some distinctive traits; these may be obtained, either by adopting for the new section some special resource of the Motive (for instance, Imitation in contrary motion), or by inventing more striking and characteristic counterpoints than those of the First Section, or by introducing new episodic members. In this way, too, necessary provision may be made for sustaining interest. See Ex. 94, Note *2).

c. At the same time, it is desirable (though not indispensable) to institute some points of manifest resemblance, or even exact confirmation, ~ between the sections, by reproducing some portion of the preceding section, — of course in a different key, and, if possible, with inverted parts (i.e., changing the former upper part to the lower, and vice versa). Review par. 39b. And see pars. 55 and [par.] 56.

This parallelism of design is strikingly illustrated in the 1st 2-voice Invention of Bach; — the last five measures of the Second Section (measures 11–15 of the entire Invention) almost exactly corroborate the last five measures of the First Section (measures 3–7); but they are transferred to the next higher step; the former upper part becomes the lower, and its contrapuntal associate is partly reconstructed, — near the end of the section.

d. The modulatory aim of the Second Section is, generally, the Relative minor from a major beginning, or the Dominant key from a minor beginning. In a word, the first two cadences are usually made in the keys most closely allied to the original key, that is, the Dominant and the Relative; in a major Invention the Dominant cadence comes first and the Relative next; in a minor Invention the Relative comes first, and then the Dominant. Other related keys may, however, be substituted. Review par. 40g, and [40]h.

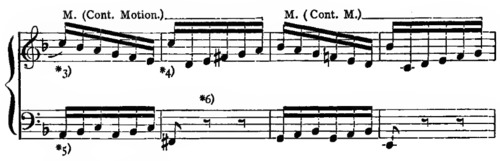

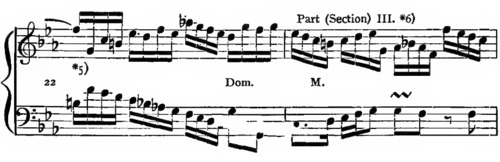

*1) First review Exs. 87, [ex.] 88, [ex.] 92. The Second Section begins, after an elision, with the Motive in the lower part; it is followed, not by an Imitation, but by a Sequence, thus confirming the general structure of Section I, which was very largely sequential (par. 42c).

*2) This contrapuntal associate, upon one tone, is an obvious lapse of contrapuntal energy; it is a temporary and intentional subjection of “contents” to “form.” The trill, however, lends vitality to the tone; and, altogether, it contrasts with the preceding Counterpoints sufficiently to individualize its Section (par. 42b). This is emphasized by its recurrence, in the lower part, a few measures later.

*3) Here the Contrary Motion of the Motive appears for the first time. It is reproduced in the prevailing sequential manner.

*4) Unessential change in quality of intervals; comp. par. 28b, [28] c; Ex. 70A, with Notes.

*5) This counterpoint corresponds to one which appeared near the end of the First Section (par. 42c). Review Ex. 92, Note *1).

*6) Comp. Ex. 91, Note *3).

*7) Here the original motion of the Motive is re-adopted. The counterpoint in the lower part is unusually powerful and characteristic. During this the movement into the Dominant key is effected (par. 42d).

*8) The derivation of the Episode is apparent.

*9) See par. 20c.

EXERCISE 12.

A. Analyze the following specimens of the Second Section, defining, as before, every element; particular attention must be given to comparison of each with its foregoing First Section:

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 1, meas. 7–15.

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 7, meas. 7–13 (symptoms of an additional cadence in the 9th measure).

- Bach, 2-v. Inv., No. 3, meas. 12–24 (M. apparently “reconstructed” by addition of 3 introductory tones; par. 42b.)

- Bach, Partita No. 3, “Fantasia,” meas. 31–66.

B. To each of the examples of a First Section, invented in Exercise-n B and C, add a Second Section, according to the above directions. Review par. 41a. [41]b, [41]c, [41]d.

The Third (as final) Section.

43. If the Invention is to embrace but three sections (perhaps the most common number), the Third Section (or final one) tends to regain and re-establish the original key. This will determine its general modulatory design, which, like all terminal sections of musical form, is very likely to include a more or less positive presentation of the Sub-dominant keys.*

a. Whether the Third Section is to constitute the climax of the form, the definite and intentional culmination of the progressive development within the preceding sections, or not, it is at least more subject than these to the demand for increased interest; and therefore the most attractive and ingenious methods of manipulation should be enlisted. These may consist in the more striking (possibly hitherto untried) species of Imitation; or in more characteristic and effective counterpoints, or in more elaborate episodic passages; or, perhaps best of all, in one or more forms of Stretto-imitation (par. 36); or in all of these together.

b. Care must be taken, however, not to diverge too widely from the prevailing character of the foregoing sections; and while it is by no means necessary to return to the beginning and corroborate the main contents of the First Section, as is done in the Third “Part” of the tripartite Song-forms* (see par. 49a), it is still desirable to employ some method of confirming one or the other of the preceding sections. Review par. 42b and [42]c.

See Bach, 2-v. Invention No. 1. The parallelism between Sections I and II, already cited, is again exhibited in almost exactly the same manner in the Third Section, which, in measures 19–20, copies measures 3 and 4 (in Section I), and measures 11 and 12 (Section II), — both parts in the Contrary motion of their former contents.

c. The final cadence is made in the original key, and, as a rule, with more emphasis than the intermediate cadences, — frequently strengthened by auxiliary (inner) tones. See Ex. 93, No. 6.

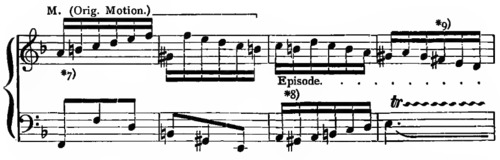

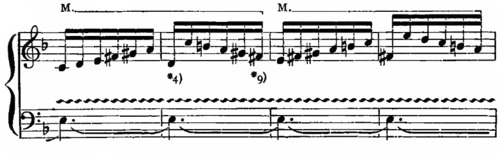

d. Sometimes, however, this cadence is evaded, by using the chord of the VIth step instead of the Tonic, in which case a brief Codetta is added. For illustration:

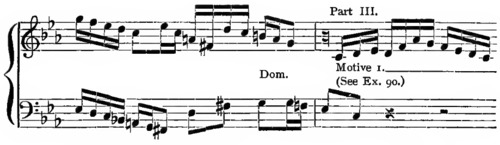

*1) The Third Section begins, after an elision, with the M., again in the lower part; see Ex. 94, Note *1). It immediately modulates down into the Sub-dominant key; see par. 43; also Ex. 57, No. 1 (par. 19d).

*2) The counterpoints, in this section, differ almost constantly from those of the foregoing sections; see Ex. 87, Note *1). But observe Note *5).

*3) This “counterpoint” agrees with the preceding one.

*4) Comp. Ex. 91, Note *3).

*5) These two measures exactly confirm measures 5 and 6 of the First Section (Ex. 87), in both parts.

*6) Here the expected perfect cadence is evaded, by substituting the VI for the I (par. 43); what follows is a Codetta, in which, again, the Contrary Motion of the M. happens to be employed, as in Ex. 94, Note *3).

*7) Unessential change in quantity of intervals; par 28b.

Additional Sections.

44. If the Invention is to be extended to four, or perhaps even more, sections, the above details of Section III will need to be modified:

(1) With regard to the adoption of the most effective and interesting resources of thematic development, which, in this case, are more likely (though not certain) to be deferred to the final section; and

(2) With regard to the cadence, which will be made in some other related key, — preferably in one of the Sub-dominant keys, — thus also influencing the general modulatory design.

The conditions of individuality and confirmation (par. 42 b and [42] c) are valid, as before; while those of par. 43 a, [43]b, [43]c, and [43]d refer, in any event, to the final section.

EXERCISE 13.

A. Analyze the following miscellaneous examples, as before:

- Bach, 2-v. Invention No. 1, meas. 15 to end.

- Bach, 2-v. Invention No. 7, meas. 13 to end (possibly four Sections in all, as intimated in Exercise 12A; brief Codetta).

- Bach, Partita No. 3, “Fantasia,” meas. 66 to end (four Sections in all, the third one cadencing, very exceptionally, in the original key).

- Bach, Partita No. 2, “Sinfonia,” 3rd movement (3-4 time); meas. 20 to end (3 Sections in all; Section II largely episodic; Section III very similar to II, but shorter, and in different keys).

- Bach, English Suites, No. 4, “Prélude,” meas. 12–20 (Section II, cadence in original key; the auxiliary inner tones may be ignored).

- Bach, English Suites, No. 2, “Prélude,” meas. 1–55; one long Section, with an occasional very vague intimation of cadential purpose. In meas. 47–51 a Codetta is added, with modified repetition in the following 4 measures. The prevalence of the principal key is owing to the Divisions that follow. The auxiliary tones may be ignored. The remainder of this example is cited in par. 67, which may be briefly referred to.

B. To each of the examples invented in Exercise 11B, and continued in Exercise 12B, add a third (as final) section, according to par. 43. Review par. 41 a, [41]b, [41]c, [41]d.

C. To the original examples extended in Exercise 12B, add a third and fourth section (par. 44).

D. Write two complete Inventions, one in minor and one in major, with original (short) Motives; the number of sections optional, but neither less than two nor more than five.

The Invention in Two-Part Song-form.

45. While the “sectional” form is most consistent with the character of such polyphonic compositions as the above, representing the continuous development of an adopted thematic germ, it is nevertheless possible to cast them in the mould of some homophonic design, like the Two- or Three-Part Song-forms.

When this is done, the treatment of the “Sections” must be modified to conform with the more definite specific conditions of the “Parts.” Review par. 39a.

This will probably affect the extent, which is usually greater in the “Part” than in the “Section”; and there is generally a marked distinction in the character of the cadences. As stated in par. 40h, second clause, and illustrated at the beginning of Exs. 94 and [ex.] 95, the “Section” commonly ends with an elision; i.e., the cadence-chord (or end) of one section is at the same instant the beginning of the next.

This is more rarely the case in the “Part,” which is likely to have a firmer, more decisive (i.e., longer) cadence-interruption.

Further, a certain predominance of the structural idea over the details of thematic texture will also be evident, when the Part-forms are adopted, and this will influence the general character; it may lead to greater freedom of contrapuntal treatment, in favor of the distinctive conditions of the homophonic style; a more definite melodic character, more regular succession of 4-measure phrase-groups, or even distinct period-formations may prevail.

46. The primary grade of the Two-Part Song-form. This differs, when applied to the Invention, but little from a Two-section design, the main details of which are given in par. 40 and par. 43; i.e., the First Section stands for Part I, though possibly extended slightly beyond the limit of the ordinary “Exposition,” and ends with a somewhat stronger form of cadence (par. 40h). The Second Part may be a trifle longer; it should exhibit the traits of confirmation explained in par. 42c; and must close with the perfect cadence in the original key, possibly followed by a Codetta.

This form is illustrated in Bach, 2-v. Invention No. 8. The First Section, or “Part” (already analyzed), embraces the first 12 measures, — a regularity of design suggestive of the group of 3 phrases; it closes with a distinct perfect cadence in the Dominant key. Measures 12–14 (beginning of Part II) correspond to the beginning of Part I, with inverted voices; measure 15 is a new episode; the following 4 measures are a sequence of these, with inverted voices; measures 20–25 are thematic, but new in treatment, involving sequential announcements of the M. in Contrary motion; measure 26 to the end exactly corroborates the last 9 measures of Part I, but transposed one fifth lower, in order to close on the original Tonic. See par. 48a, second clause.

See further, Bach, 2-v. Invention No. 10. Part I closes in measure 14 (already analyzed as Section I); Part II in measure 30, with an evaded cadence, followed by an extension of 3 measures.

The Genuine Two-Part Form. The First Part.

47. In the genuine (broader) Two-Part Song-form,* the First Part may be still more extended; possibly (though somewhat rarely) embracing two sections, the first of which fulfils the conditions of an “Exposition,” with a comparatively light cadence, while the second one carries out the modulatory design, closing with a strong perfect cadence, — always in the Dominant key (whether major or minor). More commonly, however, these details are all contained in one single (long) section, which in some cases (e.g., in old Dance-forms) assumes the character of a Period or Double-period. See par. 45, last clause.

The First Part is very frequently repeated; generally with “1st and 2nd ending,” the second one with a more complete check of the rhythmic movement.

In the following examples the First Part only is to be analyzed, but with great minuteness: Bach, English Suite No. 1, “Bourrée I;” the First Part bears many evidences of regular Double-period form, parallel construction; it contains 16 measures, of which measures 9–12 corroborate measures 1–4 almost exactly. It is repeated.

Bach, French Suite No. 3, “Allemande”; the thematic germ is unusually small, only a figure of 4 tones; a perfect cadence is made on the Dominant, in the 10th measure, and a Codetta follows; a very light cadence in the Relative major key, in measure 6, appears to divide the First Part into two sections. The Part is repeated.

Bach, French Suite No. 4, “Gavotte”; the Motive is small (5 tones); the form of Part I is clearly a “parallel period”; it is repeated, with two endings.

Bach, French Suite No. 5, “Courante”; Part I is evidently a parallel Double period of 16 measures, with sufficiently obvious semi-cadences every 4th measure the Contrary motion of the M. occurs in measure 7; the evidence of three-voice writing in measure 8, and the auxiliary tones in measures 1 and 16, may be ascribed to the influence of the structural idea; they do not affect the actual two-voice style. The cadence is extended by a fragment of the Motive. The Part is repeated.

Bach, Partita No. 2, “Allemande”; Part I contains two sections, the first one closing in measure 6 on the original Tonic. The copious auxiliary tones assume sometimes the importance of a third part; but, as intimated above, they do not seem to affect the prevalent two-voice texture; some of them represent merely a device of notation.

Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 10; Part I is one long section, suggestive of Phrase-group form; it closes on the Dominant, and is repeated, with two endings. Same work, Vol. II, Prelude 8; Part I, 16 measures long, suggestive of large period-form.

The Second Part.

48. The Second Part of a genuine Two-Part Song-form is usually much more distinctly individualized than any “section” of the smaller forms. Its thematic basis may be defined in the following ways:

a. Most commonly, the same Motive (that of the First Part) is employed in Part II. It may preserve its original form exactly; or may possibly be slightly modified or reconstructed (as already witnessed in Bach, 2-voice Inventions, No. 3, meas. 12–13; and No. 7, meas. 13–14). Usually the Motive is announced first alone, or accompanied only by unessential auxiliary tones, as at the beginning.

In this case (when the same M. is retained) the characterization of the Part devolves largely upon the contrapuntal associates, which may be new and more striking than in Part I.

The condition of confirmation still demands fulfilment, as shown in par. 42c. This is most effectually realized by the very common device of ending the two Parts with the same member, — extending through an optional number of measures (from one up to ten or more). The member thus employed must reappear in a different key (Part I closing, probably, on the Dominant, and Part II on the Tonic*); and frequently the voices are inverted.

The Second Part may also consist of two (rarely more) sections, and is sometimes repeated.

See Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 8; Part II begins with the original form of the M., but the counter-motive is entirely new and characteristic in rhythmic form; it reappears in measures 3, 16, 17, and 18 of the Second Part; in measure 12 another new counter–motive appears, confirmed in the next measure. Measures 5–7 of Part II corroborate measures 3–5 of Part I (inverted voices, and somewhat modified); and measures 9–13 closely follow measures 6–10 of Part I (voices not inverted). The last 5 or 6 beats of the two Parts are identical, except in key.

Bach, Partita No. 2, “Allemande”; Part II uses the M. unchanged; it embraces two sections (like its First Part), cadencing in the 6th and 16th measures. The last 4 measures of the two Parts correspond, but in different keys and with inverted voices. Part II is also repeated.

Bach, French Suite No. 4, “Gavotte”; Part II uses the M. of the First Part, but much more persistently than the latter, and often in Contrary motion. There are no obvious traits of parallelism between the Parts. Both are repeated.

Bach, French Suite No. 5, “Courante”; Part II very similar to Part I in form and contents; the M. is retained without change, the form is well-defined Double-period; Contrary motion again appears, this time in measures 8 and 9; the final Phrase (4 measures) corresponds almost exactly to the ending of Part I, excepting the transposition. Both Parts are repeated.

Bach, English Suite No. 1, “Bourrée I”; Part II contains two sections, separated in measure 8; the M. is slightly altered from its original form and length; from measure 13 to 22 the polyphonic character relaxes notably, — the sequential successions and repetitions in the upper voice (though thematic) and the simple rhythmic accompaniment in the lower, lend a lyric effect to the passage that contrasts well with the rest. The Second Part ends in measure 24; a 4-measure Codetta, with nearly exact repetition, follows. Part II is repeated.

Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. I, Prelude 17 (entire). the M. consists of two similar measures, of which, now and then, only one measure is used. Part I contains two sections, separated in measure 9; the auxiliary tones, the lyric quality of the M., and its general treatment, impart a somewhat homophonic complexion to the whole Prelude. (See par. 83.) Part II utilizes the same M., and adopts a very similar mode of treatment, so that the Parts are more than ordinarily parallel, throughout; measures 26–33 correspond closely to measures 10–16 (extended one measure) with inverted voices. A Codetta of 10 measures follows.

Händel, Harpsichord Suite No. 16, “Gigue” (entire); Part I, a 6-measure Period; Part II contains two sections.

b. Quite frequently the Contrary motion of the M. is adopted as thematic basis for the Second Part. It should be derived from the original M. in the manner defined in par. 29a (Exs. 72 and [ex.] 73), and must then be shifted (transposed) to the key or harmony with which Part II is to begin, — possibly with such modifications as may facilitate its adjustment. Comp. Ex. 74, Note *4), entire. When this is done it is likely, though by no means certain, that the Contrary motion will be held in abeyance during the First Part.

The new form of the M. may either extend to the very end of Part II, or it may be exchanged for the original motion in the later course of the Part; or the two forms of the M. may alternate, more or less regularly, throughout.

This device is a characteristic feature of the so-called Gigue-form (par. 51), in connection with which it will be more fully illustrated.

See Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 10. the M. of Part I (already analyzed) appears at the outset of the Second Part, but in Contrary motion, and extended by sequence to four measures (double its original length). In this new form it appears twice in the First Section (ending in measure 24 of the Second Part), and again twice at the beginning of the Second Section; the last announcement is followed by a recurrence of a long passage from Part I (measures 33–55, corresponding closely to measures 23–48 of the First Part, with inverted voices for a short distance); during this parallel passage the original motion of the M. naturally reasserts itself. The cadence falls in measure 55, but is evaded (by a VI, — par. 43d), and a Codetta is then added.

Bach, English Suite No. 5, “Allemande”; M. of one measure in upper part, lower part auxiliary; the original motion of M. recurs near the end.

c. In somewhat rare instances a new Motive is adopted for the Second Part. Though thus quite independent, it should be intimately related in general character to the first Motive. As before, the new thematic form may be retained throughout the Second Part; but it is much more likely that the first Motive will reappear, near the end,—possibly in alternation with the new one; more rarely in conjunction with it, when, be it by accident or design, they harmonize. For illustration: The First Section partially shown in Ex. 90, after being continued in a very similar manner up to its cadence (E♭ major), in the 15th measure, runs on as follows:

*1) Compare the new M. with the first one (Ex. 90); they are strictly kindred, though actual similarity is avoided. Observe, further, that the new M. is introduced during (across) the cadence (par. 40h, final clause).

*2) The peculiar notation of a (♮) is owing to Bach’s conception of this 2nd beat as Dominant harmony of c minor, with a as ascending passing-note. Comp. par. 20b (and [20]c).

*3) First half of the Motive. The parts cross here, briefly.

*4) A few measures later the first M. recurs (see Ex. 98).

See also Bach, French Suite No. 3, “Allemande.” the M. of Part II, like that of Part I (already analyzed), is very brief; though strongly suggestive of the first M. in Contrary motion, it is really new (as its own Contrary motion, further on, proves). The Part has two sections, separated in the 4th measure; its perfect cadence is evaded in the 10th measure (by a VI), and a brief Codetta, for which Contrary motion is exclusively utilized, follows. This Part is even more persistently thematic than Part I, containing scarcely an episodic note. It is repeated.

EXERCISE 14.

A. Write a complete 2-voice Invention (M. original), in the primary grade of Two-Part Song-form (par. 46). Review par. 41a, [41]b, [41]c, [41]d.

B. A complete Invention (in major) in broad Two-Part Song-form, according to par. 47 and 48a, both clauses.

C. A complete Invention (in minor), with Contrary motion of the M. in Part II, according to par. 48b.

D. A complete Invention (mode optional), with a new M. in the Second Part, according to par. 48c. A Codetta may be added to each Part. See par. 54.

The Invention in Three-Part Song-form.

49. In all Three-Part forms there is, in addition to the above two Parts, a more or less distinctly marked return to the beginning, and consequent recurrence of the essential thematic contents of the First Part or Section; it is the fulfilment of this structural condition which devolves upon the Third Part.* This affects, primarily, the cadence of the Second Part, which should be made upon the Dominant of the original key, and may therefore influence the later modulatory and thematic design of the Part.

The Primary Grade.

a. The primary grade of the Three-Part Song-form, when applied to the Invention, will resemble the Three-section design, explained in par. 40–[par.] 43, with the significant exceptions, however, that the Third Section is not to be, as there, merely the continuation of its predecessors, but must represent the Return of the original key, and must reproduce a portion of the early contents of Section I (perhaps no more than one or two measures); and that, consequently, the Second Section must be so conducted, near its end, as to lead to this result. (Compare par. 43b.) For example:

* Homophonic Forms, par. 81.

*1) With reference to the uncertainty of definition, compare par. 39a. The Motive is unusually long, and might be called a “Subject” (par. 38a).

*2) Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 2.

*3) This cadence is very indefinite; hence the impression of “sectional” form, and the distinction “primary grade” of the tripartite design.

*4) This measure and the following 7 correspond exactly (excepting the transposition) to measures 3–10 of Section I, but with inverted parts; one sequential measure follows, and then the last measure of the Second Part, leading to a brief but definite Dominant ending.

*5) The upper part corresponds to the conduct of the lower at the end of Part I.

*6) The purpose of this Third Section to reproduce the initial members of the First Section, though somewhat indistinct, is nevertheless sufficiently obvious to establish the tripartite design.

Furthermore, Ex. 96 is completed as follows:

*1) First half of Motive 2.

*2) This second member of the Episode (which began in the 17th measure) is less closely related to the M. than the foregoing.

*3) Up to this point the Third Part agrees exactly with the initial members of Part I (see Ex. 90). It is a much-abbreviated recurrence of the latter.

See also Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. I, Prelude 14. Part I (already analyzed) closes in measure 12 with a strong Dominant cadence; in the Second Part many auxiliary tones are used, but the impression of essentially 2-voice polyphony is not disturbed; the Dominant semi-cadence in measures 18–19 indicates the termination of Part II; and the following tones are, under these circumstances, a sufficiently evident return to the beginning,—though no more than one measure is reproduced, and that with inverted voices. This somewhat vague Third Part is very brief, closing in measure 22; a Codetta, corresponding to the beginning of Part II, follows.

The Genuine Three-Part Form.

50. In the genuine (broader and more clearly defined) Three-Part Song-form, the details of Part I correspond to those given in par. 47, which review; and the conduct of Part II corresponds to all the details of par. 48a, [48]b, and [48]c, — excepting such as concern its cadence, which, in the Three-Part design, must be made on the Dominant, or, at all events, upon such harmonies, and in such a manner, as to prepare for and lead decisively into the recurrence of the first measures (as beginning of Part III).

a. As before, the thematic basis of the Second Part may be:

(1) The same Motive (usually with new, and more or less characteristic, counter-motives),—par. 48a, first and second clauses;

(2) The Contrary motion of the original Motive, as in the “Gigue” form (see par. 51); or

(3) A new Motive, — par. 48c.

b. The object of the Third Part is, as usual, to re-establish the principal key, and to re-announce the original Motive and its Imitation as they appeared at the outset, in a sufficiently accurate manner and through a sufficient number of measures to identify itself as the corroboration of the First Part. In some cases, where the design is broad, the parallelism extends through a large portion of the Third Part (perhaps with inverted voices, and occasional modifications), or even to the end, — excepting, of course, the necessary change of modulation and cadence. But more commonly it is limited to the first two or three measures, and the remainder of the Part is then elaborated independently, and, as climax of the form, as ingeniously and effectively as possible. Review par. 43a, which has peculiarly direct bearing upon “Part III.”

When the Second Part has used the Contrary motion of the Motive, the original motion is resumed at the beginning of Part III, and is then either retained to the end, or, far more effectively, the two forms of the M. subsequently appear in more or less regular alternation, or even in conjunction (as Stretto). And precisely the same principles apply when Part II is based upon a new motive (as in Exs. 90, [ex] 96, [ex] 98).

See Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 3; Part I (already analyzed) closes in measure 12; Part II contains two well-defined sections, closing in measures 24 and 38; between the last cadence and the beginning of Part III (end of measure 42) a brief passage intervenes, which, though largely thematic, serves the purpose of a Re-transition,* or returning passage; Part III corroborates the first 4 measures of the First Part exactly, transposes and inverts the following four, then resumes the original line (transposed), but cadences on the VI (par. 43d); a Codetta follows. Throughout the Second Part the M., as already seen, is reconstructed by the addition of three preliminary tones; this form recurs once, in the Codetta.

Bach, French Suite No. 2, “Air”; the M. (one-half measure) is announced in the upper part in a somewhat imperfect form, and imitated in slightly altered Contrary motion; Part II begins with Contrary motion, but otherwise maintains the original motion; it has two well-defined sections, of 4 measures each; Part III (the last 4 measures) is vague in effect, though the structural purpose is clear; during the first 2 measures the lower voice agrees almost exactly with the upper voice at the beginning of Part I.

Bach, French Suite No. 4, “Air”; Part I largely episodic; the Contrary motion of the M. prevails in the Second Part, which contains two sections; Part III corresponds very closely to the First, — transposed after one and one-half measure, without other changes.

EXERCISE 15.

A. Write a 2-voice Invention (M. original) in the primary grade of the Three-Part Song-form (par. 49a).

B. An Invention (in minor) in genuine Three-Part Song-form, according to par. 50: in Part II the same M., but with new and characteristic contrapuntal associates. First review par. 41 a-d; and see par. 54.

C. An Invention (in major or minor), employing the Contrary motion of the M. in the Second Part.

D. An Invention, with new M. in Part II.

The “Gigue.”

51. The adoption of the Contrary motion of the Motive as thematic basis for the Second Part (already touched upon, in par. 48 and par. 50a), is so common in the “Gigue” as to constitute a partly, though not definitely, distinctive trait of that old Dance-form; and the term “Gigue-form” is therefore often applied to a polyphonic Invention thus designed, irrespective of its character. On the other hand, many examples of the old-fashioned Gigue may be found in which the Second Part uses the original Motive, or a new one, as in ordinary forms.

* Homophonic Forms, par. 90c

The design of the whole is usually the Two-Part (more rarely Three-Part) Song-form, with repeated Parts. The most common measure is  . Review par. 48b. For illustration, see —

. Review par. 48b. For illustration, see —

Bach, French Suite No. 2, “Gigue”; M. two measures in length, imitated at once in Stretto; Part I is divided into two sections by a brief but decisive cadence in the 23rd measure (Relative key); Part II uses the Contrary motion for 20 measures, when two announcements in original motion lead to a Dominant semi-cadence; Contrary motion is then resumed, though the next (last) section is largely episodic; the evaded form of the cadence occurs 10 measures before the end. Two-Part form, each Part repeated.

Bach, French Suite No. 6, “Gigue”; Part I has two sections, terminating respectively in measures 8 and 16; an episodic Codetta of 8 measures is appended, based upon a motive suggestive of the Diminution of the original M. (par. 31b); Part II uses Contrary motion, chiefly in the lower part, and with extensive episodic interruptions; its first section ends in measure 10, and its second one 5 measures from the end; the final measures are a partial recurrence of the former Codetta. The preponderant episodic portions, throughout this Gigue, seem to be based upon an additional (auxiliary) Motive, or several Motives, generated out of the 3rd measure. Compare par. 52a.

Bach, English Suite No. 1, “Gigue”; M. of 1 measure, imitated in Stretto; Part I contains two sections, and a Codetta of 4 or 5 measures; Part II begins with a curious version of the M., — the first half only in Contrary motion, the second half as before; this version alternates with the original form during the First Section (5 measures), and again during the Second Section, which is its almost exact sequence; a Third Section follows, and the added Codetta corresponds exactly to the former one.

Bach, French Suite No. 4, “Gigue”; in the 4th and 5th measures, and once or twice later, the notation represents three-voice texture, but the effect is distinctly that of auxiliary tones; Part I has but one section, followed by a Codetta (measure 22) beginning with a quaint modification of the M. (in the lower part), — compare par. 33; Part II employs Contrary motion throughout its two sections, up to the Codetta (7 measures from the end); the Codetta begins with one announcement of the M. in Contrary motion, not included in the former Codetta, and then reproduces the latter in its full length, with inverted parts.

Bach, English Suite No. 5, “Allemande”; in the Second Part a modified form of the Contrary motion is adopted; there are occasional brief intimations of 3-voice texture; the original motion of the M. recurs near the end.

Bach, English Suite No. 4, “Gigue”; here also, as in the preceding examples, there is an intimation of 3-voice texture (in measures 5–8 only); the lower part, during measures 1 and 2, though thematic enough to simulate a genuine Imitation, is nevertheless only auxiliary, — the M. is 1½ measure in length, and its first real Imitation begins with the last tone in measure 2; the last 5 measures of Part II correspond to the ending of Part I. Each Part is repeated.

The Invention with Two (or more) Motives in Alternation.

52. A second (new) Motive may appear not only at the beginning of the Second Part, as specific basis of the latter (par. 48), but may be introduced and developed in closer connection and alternation with the first, or principal, Motive.

a. Such an additional thematic germ may be so unimportant in character and extent as to subserve, chiefly or entirely, the episodic purposes, in which case it is to be called an Auxiliary Motive (or Figure), rather than “2nd Motive.”

An example of this kind has already been seen in Bach, French Suite No. 6, “Gigue”; and others will be cited later.

b. When the new M. is more nearly or completely co-ordinate with the principal (first) one, it may appear at the beginning of the second (possibly a later) section, and become its thematic basis. Or it may enter into the polyphonic texture still earlier,—during the First Section, or Part, — and be utilized thereafter throughout the Invention, in more or less constant close alternation (not simultaneous conjunction) with the principal Motive.

As already stated (par. 48c), the new M. must, while asserting a certain measure of distinct individuality, still be conceived in intimate consistency of character with the first Motive.

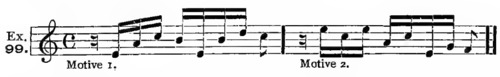

For illustration, see Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 13:

The first (principal) M. is used during 2 measures; the 2nd M. during the rest of Part I (up to measure 6); the same arrangement prevails, very nearly, during the First Section of Part II (measures 6–13); in the remainder of Part II (up to measure 18) the 2nd M. appears alone, somewhat modified; in Part III (measure 18 to the end) the two Motives are employed, in closer alternation.

Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 23:

The 1st M. appears only at the beginning of Part I, with one Imitation, partly in Contrary motion; the 2nd M., which, but for its domination, would be regarded merely as an auxiliary figure, supplies the basis of development up to measure 8, after which fragments of M. 1 lead to the cadence (measure 12); Part II extends to measure 37; its First Section, ending in measure 17, is episodic, but derived from M. 1; an independent episode follows, suggesting a third M. (compare par. 52c); in measure 23 the second M. again asserts itself, and continues some time, though fragmentary, measures 29–32 closely resemble the episode of the foregoing section; Part III (measure 37 to end) is much like the First Part, but the 2nd M. is absent. There are several evidences of 3-voice texture, but scarcely enough to be conclusive.

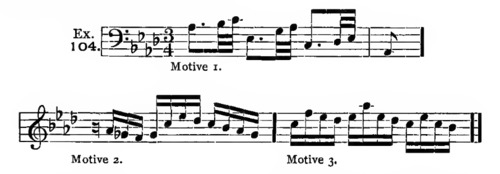

The whole example belongs, more accurately, to the Prelude-class (Chap. IX). And the same is true of Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 13, in which the following contrasting thematic members are discoverable:

Of these, Motive 2 appears to be the more essential and important. The design is 3-Part Song-form; Part II contains three well-defined sections; in the first one the two Motives are announced in conjunction (simultaneously); Part III resembles Part I very closely, but is abbreviated. A coda of 8 measures is appended.

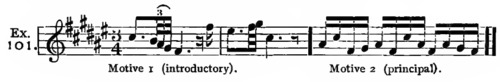

Händel, Clavichord Suite No. 7, “Andante,” employs the following Motives:

The design is 3-Part Song-form, Part III somewhat vague and abbreviated.

Händel, Clavichord Suite No. 16, “Allemande,” is a very clear exposition of the following, in almost constant close alternation:

The design is 2-Part Song-form, each Part containing two sections, and repeated. The thematic development is unusually regular and perspicuous.

c. More rarely, three Motives participate in the development of an Invention; either (1) as the respective thematic basis of three successive sections, or (2) in closer and more constant alternation with the first (principal) M., or with each other, in any order.

An illustration of the first of these methods is found in Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 4 (3-voice polyphony, and therefore to be reviewed in minuter detail in Chap. VII); a different M. is employed in each one of the first three Sections (beginning in measures 1, 17, 27), the first announced in the upper, the second in the inner, and the third in the upper part.

The second method is illustrated in Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 17 (belonging properly to the “Prelude “-species, Chap. IX); the following Motives appear, in measures 1, 2, and 7:

Besides these, there are meagre evidences of additional brief auxiliary Motives. The principal M. (No. 1) is each time accompanied by a body of auxiliary tones, almost equivalent to two extra voices, but their unessential quality is nevertheless entirely obvious; the remainder of the texture is two-voice. The form is sectional (par. 39); each of the four Sections begins with the principal M., and employs both of the others generously, and with considerable regularity of design (M. 2 occasionally in Contrary motion). Section 2 begins in measure 17, Section 3 in measure 34, Section 4 in measure 50. The latter has quite a definite semi-cadence in measure 63, suggesting a possible fifth Section from that point to the end. The episode in measures 52–59 is based upon the first contrapuntal associate of M. 3 (measure 7), which is so prevalent that it might be regarded as a 4th Motive.

The Lyric Invention, with a Long Theme.

53. The 2-voice Invention may, exceptionally, be based upon a thematic sentence of greater length than the ordinary Motives, seen in the above examples. Such a lengthy theme is very likely to represent the regular 4-measure Phrase, or even 4- to 8-measure Period-form, with a correspondingly definite melodic design, usually distinctly lyric in character, and with a well-marked semi-cadence (upon either a Tonic or Dominant chord).

Obviously, so extended a Motive cannot be announced (imitated) effectively very often in the course of an ordinary Invention, at least not at its full length; and therefore the development, while none the less strictly polyphonic, will necessarily be more largely episodic than usual; and in general the structural idea and considerations of “form” will prevail almost constantly over the thematic purposes (compare par. 45, last clause). The episodic interludes will probably be derived from some figure or figures of the large Motive, though they may be independent. (Compare par. 38d and par. 41b; see also par. 42c.)

See Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 14; the theme is announced in the upper part and extends into the 4th measure; it consists of a figure two beats in length, which alternates with its Contrary motion, excepting in the 3rd measure; the lower part is “auxiliary” in character, though it is again employed as “counterpoint” to the Imitation of the theme (in measures 6–8); measures 4, 5, and 9–16 are episodic, derived directly from the germinal figure of the theme; one more announcement of the entire theme, in the lower part (in shifted rhythm), leads to the concluding cadence. The entire design appears to embrace but one long section, as Phrase-group.

Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 24; theme of 4 measures, announced in upper part and imitated immediately in lower part, with different counterpoint; an Episode follows, based during 4 measures upon a new auxiliary figure, and then for 4 more measures upon a figure from the second contrapuntal associate (measure 7); the Second Section begins in measure 17, announces the theme four times in unbroken succession, using two former and two new “counterpoints”; it then becomes episodic (measure 33), the lower part corresponding to the upper one of the former Episode, during 4 measures, while the following 4 measures are a new Episode; the Third Section (measure 41) announces one-half of the theme, first in the upper, then in the lower part; an Episode follows, 8 measures of which correspond very nearly to the first Episode (excepting in key); the remaining measures (53–59) are new Episode and cadence. A Coda is added, containing one announcement of the theme, and a few effective thematic fragments.

Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 6; Two-Part Song-form and 5-measure Codetta; theme extending into the 5th measure; both Parts are largely episodic, — especially Part II, — but constantly in close touch with the contents of the theme.

Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. II, Prelude 15; Two-Part Song-form; theme 3 measures long, appearing in a modified form of Contrary motion in Part II (compare par. 51); the extensive episodic passages, which contribute to the Prelude-like character of this Invention (see Chap. IX, par. 83), are strictly congruous, if not of thematic derivation. The last six measures of the two Parts correspond.

The Student’s Attitude Toward the Prescribed Tasks.

54. In working out the required Exercises in these grades of 2-voice Polyphony, the student need harbor no fear that he may imitate the given authoritative examples of Bach too closely, and thus perhaps unconsciously acquire the unwelcome habit of conceiving and writing in the somewhat antiquated manner of these old-fashioned compositions. The propagation of this particular style — the multiplication of pieces for which our modern ears have but little sympathy — is not the aim of the student’s present labors; it is simply the exercise of contrapuntal discipline within the dominion of these forms, as a means to an end, — an end which may be as modern and original as the student (or the listener) could desire.

There is but little likelihood that the pupil will wholly escape the influence of modern musical thought, especially if he be observant (as successful students invariably are), alert to recognize and to appropriate the acquisitions of recent times, whether in the polyphonic or in the homophonic domain of musical creation.

Polyphony is merely a product, resulting from the employment of the contrapuntal method; and this method may be applied in dealing with any phase of musical style, romantic, classic, dramatic, or archaic. The distinction rests mainly, perhaps, upon the choice of harmonic basis, out of which all Polyphony must emerge, just as well as Homophony (par. 11); for this harmonic element it is which has grown “modern,” leaving former simpler customs of harmonic progression behind. The distinctive contrapuntal “method” adopted for the presentation of the harmony is, however, not thus subject to the changes of time; Polyphony is the embodiment of the same principle in the twentieth century as in the fifteenth; but its character and complexion will differ, as the harmonic material becomes richer and more pliable.

There can be no excuse for writing an unattractive Invention in our day, on the ground that it must be produced by contrapuntal methods. Nothing is devoid of interest in which the operation of a quick imagination is discernible; and nothing discloses, from the proper point of view, a more powerful and constant stimulus to the imaginative faculty, than the contrapuntal methods of tone-association.

Brief reference may be made to par. 72 and par. 82. And the following effective specimens of the modern Invention for two parts should be thoroughly analyzed:

Rubinstein, Prelude, op. 24, No. 2; 3-Part Song-form; in Part I the Motive, 4 measures long, appears twice, followed by an episode (measures 9–16); Part II (measure 17) announces the M. once, in lower voice; a long and brilliant episode follows (measures 21–52), based wholly upon the last measure of the M.; in measures 35–36 the figure is somewhat concealed among auxiliary tones; a second episode (measures 53–60) is based on the first measure of the M.; a strong Dominant cadence occurs in measure 60, followed by an extraordinary organ-point, as Re-transition into Part III; the M. is announced twice in Part III (measures 77–84); from this to the end is episodic Coda, based on first member of the Motive.

Chopin, Étude, op. 10, No. 4; 3-Part Song-form; the M. lies in the upper part, measures 1–4; the texture is largely episodic, though all derived directly from the M.; there is an auxiliary harmonic accompaniment almost throughout, but the whole is distinctively 2-voice Invention-form (Prelude-species, par. 83).

EXERCISE 16.

A. Write two examples of the “Gigue “-form (par. 51), one in major and one in minor. Review par. 41 a, [41]b, [41]c, [41]d, and par. 54.

B. An Invention, in optional form, with two Motives in close alternation. Par. 52b.

C. An Invention in three Sections, with a separate Motive for each section, — returning to the first M. near the end. Par. 52c.

D. An Invention with a longer theme, of lyric character. Par. 53.

The Natural Species of Double-Counterpoint.

55. Double-counterpoint is a process; but the term is generally-applied to the product resulting from it. The counterpoint is said to be “double” when the added voice (i.e., the contrapuntal associate) presents perfect agreement with the given voice or Motive, in two different relations to the latter. These two relations always imply, in Double-counterpoint, the distinction of register, and refer to the agreement of the added part both above and below the given part; or, in a word, the counterpoint is “double” when the parts admit of inversion.

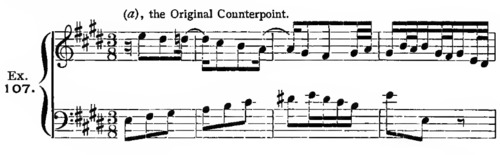

a. The inversion of the parts is effected by transferring either part toward and beyond the other (shifting it up or down, as the case may be); thus, the upper part may be shifted down, past the lower; or the lower part shifted up; or each may be shifted so that they exchange registers. See Exs. 105, 106, 107.

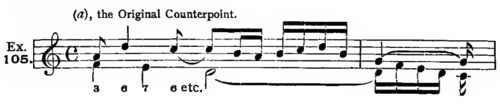

b. When one of the parts is shifted just an octave (or possibly two octaves), while the other part remains where it was, it is obvious that no essential change in their harmonic relationship takes place, because each retains its original series of letters (or tones), and the association or union of the melodies is actually the same as before; the only difference being that their respective registers have been exchanged. Each contrapuntal interval is simply inverted, and the octave-inversion of an interval, as has been amply tested, is practically identical with the original interval. For illustration:

*1) At b the two parts are inverted, the original upper part becoming the lower, and the lower the upper. The original upper part remains where it was, and the lower is shifted upward one octave, beyond the other. That no essential change takes place in the harmonic relations of the parts, is easily verified by comparing the contrapuntal intervals.

The result would be precisely the same if the lower part were to remain, and the upper part shifted down an octave:

Or if each part were shifted one octave (possibly two octaves) towards and beyond the other:

*1) Here the original lower part is shifted up one octave, and the upper is shifted down two octaves.

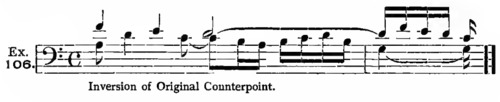

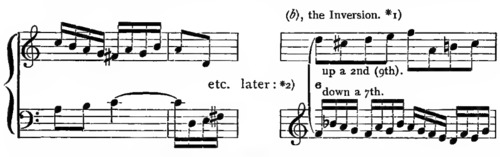

c. Further, the same result is obtained (without essential change) when the Inversion of the original counterpoint is transposed. In this case each voice is shifted toward (and past) the other in such a manner that the sum of the two shifts equals an octave; for instance, if the upper voice is shifted down a 5th, the lower must be moved up a 4th; or one a 3rd and the other a 6th; or one a 2nd and the other a 7th. For example:

*1) The upper part is shifted down a 7th, the lower up a 2nd (or 9th, which is the same thing); the original counterpoint is thus transposed bodily, as Inversion, from C major to d minor. That no other change than simple “inversion” has taken place, is shown by the first contrapuntal interval (a 3rd, becoming a 6th in the Inversion). See Ex. 86, Note *6).

*2) The inverted form does not need to be enchained with the original counterpoint, as chances to be the case in Ex. 107; it may occur and recur at any later moment in the form.

56. Such Inversions as these, in the octave or in intervals equalling an octave (or two or more octaves), are so common, so nearly inevitable in contrapuntal writing, and the product is, as has been shown, so likely to be exactly equivalent to the original, that this — the Inversion in the Octave — is called the Natural species of Double-counterpoint. Its feasibility is almost a foregone conclusion, and therefore all good contrapuntal association is, in a sense, naturally double-counterpoint.

57. No specific rules can be given for natural Double-counterpoint. The best method is to write the counterpoint as usual, and then simply test the effect of inverting the parts; any lurking discrepancies can thus easily be detected and removed. The following general points may, however, be borne in mind:

(1) The Original counterpoint should be as perfect and free from irregularities as possible.

(2) Some caution should be exercised in the use of the chord-5th, for certain irregularities that are permitted with it in the upper part become objectionable in the lower; this refers particularly to skips to or from the chord-5th, during a change of harmony. Compare par. 17d, last clause; (Ex. 50B, No. 2, the last measure, would be much worse in inverted form). See also par. 62.

A curious instance of characteristic disregard of this rule is seen in the following. Its undeniable peculiarity is palliated by broad considerations, that will become obvious to the more advanced student:

*1) The c♯ in the lower part is the 5th of the chord (I of f♯ minor). In the Inversion, the chord-5th f♯, also, is unpleasantly prominent in the upper part.

(3) If the two parts are kept within an octave (from each other), the shifting of either part a single octave suffices to effect Inversion. If the parts diverge more than an octave at any point, however, it will be necessary to shift each voice an octave (or either voice two octaves) in order to obtain Inversion throughout; and so on.

58. Frequent unconscious use has already been made of natural Double-counterpoint in the preceding exercises. Systematic application of it may hereafter be made, in the Invention, in many ways that will suggest themselves to the student. For instance:

In the sectional form, any later section may correspond exactly (or nearly) to some foregoing section, but with inverted voices, and, of course, in a different key.

Or, in the 2-Part Song-form, a portion, or the whole, of the Second Part may be an inverted reproduction of the First, in the proper key. This is strikingly illustrated in Bach, Well-temp. Clavichord, Vol. I, Fugue 10, to which brief reference may be made; the entire Second Part (measures 20–38) is an Inversion of Part I (measures 1–19) in a different key; the necessary modulation is made in measure 29, first beat (compare with measure 10).

Or, in the 3-Part Song-form, Part III may corroborate Part I in the same manner.

See Beethoven, Pianoforte Sonata, Op. 10, No. 2, Finale, measure 87 (ff) to 106.

Beethoven, Violin Son., Op. 30, No. 1, Finale, Var. V; meas. 1–8, inverted in meas. 9–16; meas. 17–24, inv. in meas. 25–32.

EXERCISE 17.

Write a number of 2-voice Inventions, applying the principle of natural Double-counterpoint, according to the suggestions in par. 58.