CHAPTER XIV.

Miscellaneous Varieties of the Fugue-form. — The Concert-Fugue.

148. It is entirely feasible, and permissible, so to elaborate the Fugue-form that, without violating any of its essential conditions or materially modifying the dignity of its character, it may exhibit those qualities of brilliancy, passion, and freedom which better adapt it for public concert use, or, in a word, enhance its effectiveness and external beauty. Such a version bears about the same relation to the more genuine, serious Fugue that the Prelude bears to the Invention. Review par. 83.

The consequent relaxation of fugue law, and general freedom of treatment, will affect: (1) The Theme itself, which may be more characteristic; (2) the tempo, which is usually more lively; (3) the number of parts, — very frequently limited to three fundamental parts, but freely augmented by the occasional addition of auxiliary lines or whole “bunches” of auxiliary tones (incidental chords); (4) the episodes, which are both more frequent and more extensive, and often nearly or quite homophonic and “figural” in character; (5) the form, which is perhaps most likely to be definite 2- or 3-Part Song-form, with firm cadences, — often embracing purely homophonic (or at most “imitatory”) transitional passages, or complete contrasting sections; (6) the dramatic design, embracing more pronounced dynamic and rhythmic contrasts, and the steadily progressive development of one or more brilliant climaxes.

The strictest fidelity to the Theme is, however, indispensable; not necessarily to the whole Theme, nor constantly, but to its pregnant or salient figures. This (the original Theme, entire, and in fragments), the contrary motion, possibly Augmentation, stretti, and an effective variety of “Counterpoints,” constitute the thematic material of the Concert-fugue; to which are to be added striking episodes (as usual, largely corroborative of each other), and all the factors which contribute to an impressive dramatic design, as a whole, and brilliancy of detail.

The most of these traits are forcibly exhibited in Mendelssohn, Pfte. Fugue in e minor (with Prelude), op. 35, No. I; 4-voice; definite 3-Part Song-form; after Part I the tempo and rhythm are gradually and persistently accelerated; Part II contains the contrary motion of the Theme (further transformed by substituting staccato for the original legato), and leads to a splendid climax in Part III, which, after a powerful bass cadenza, culminates in a distinct Coda consisting of an original chorale with running bass; the latter gradually subsides to the original tempo and rhythm, and is followed by a second brief Coda with the Theme in major, treated more homophonically. Analyze, further:

Mendelssohn, Pfte. Fugue, op. 35, No. 3; 3- to 4-voice; distinct 3-Part Song-form, contrary motion throughout Part II; in Part III, regular and contrary motion in stretto.

Op. 35. No. 5; 3- to 4-voice; sectional, quasi 3-Part Form.

Op. 35, No. 6; 4-voice; sectional, quasi 3-Part Song-form.

Op. 7, No. 3; 4-voice; large 2-Part Song-form.

Fugue in e minor (with Prelude, no opus-number); 4-voice; sectional, quasi 3-Part Form.

Bach, Organ Comp. (Peters compl. ed.), Vol. II, Fugue 2; 4-voice; stretti in last Section; many and lengthy episodes, — the Theme appears (after the Exposition) in periodic single announcements, isolated between effective episodes (mostly of consistent thematic origin, but brilliant and free).

Vol. II, Fugue 4; similar to the above; quasi 3-Part Song-form.

Vol. II, Fugue 8; 4-voice; sectional; similar to above.

Vol. III, Fugue 8; 4-voice; sectional; characteristic Counterpoints; first Counterpoint retained, approximately, until last Section. Many episodes.

Vol. IV, Fugue 3; 4-voice; 10 Sections; many episodes, similar in substance; first Counterpoint retained, approximately, throughout.

Vol. IV, Fugue 4; 4-voice; about 4 Sections, cadences vague; appears to begin with “Response”; many effective episodes, lengthy, and free, but related to the Theme and to each other.

Bach, Clavichord Comp., Peters ed. 211, No. 2; 3-voice.

Bach, “Chromatic” fugue for Clavichord (with Prelude); 3-voice; sectional.

Rubinstein, Pfte. Fugues and Preludes, op. 53, Fugue 3; 4-voice; definite 3-Part Song-form.

Brahms, op. 24 (“Händel”-Variations for Pfte.), Finale.

Raff, Pfte. Suite, op. 71, Finale; 3-voice.

Other miscellaneous examples of the Fugue of more or less free structure, or in (and influenced by) homophonic surroundings, may be found as follows:

Beethoven, Pfte. Sonata, op. 110, Finale. Pfte. Variation, op. 35, Finale.

Saint-Saëns, Pfte. Études, op. 52, No. 5; 4-voice.

Paderewski, op. 11, Variations and Fugue (Finale); 3-voice.

Nicodé, op. 18, Variations and Fugue (Finale); 4-voice.

MacDowell, op. 10, No. 5, 4-voice Fugue; independent Coda.

MacDowell, op. 13, Prelude and Fugue; 4-voice.

Guilmant, Organ Comp., op. 25, No. 3 (4- to 5-voice). — Op. 40, No. 1 (4-voice). — Op. 49, No. 6 (4-voice). — Op. 44, No. 2 (4-voice). — Op. 69, No. 4. — Op. 72. Organ Sonata, Op. 50, Finale. — Op. 86, Movement III (quasi Double; counterpoint retained).

Arthur Foote, op. 15, No. 1, Prelude and Fugue; 3-voice.

J. K. Paine, op. 41, No. 3, Fuga giocosa; 3-voice.

Aless. Longo, op. 9, Fantasia e Fuga (stile libero).

Clementi, Gradus ad Parnassum, Part III of the revised edition by Max Vogrich (Schirmer); No. 89 (orig. ed. No. 13); 4-voice. — No. 90 (orig. ed. 18); 3-voice; brief Introduction. — No. 91 (orig. ed. 25); 4-voice; brief Introduction.— No. 92 (orig. ed. 45), 4-voice; with Prelude. — No. 93 (orig. ed. 43). — No. 94 (orig. ed. 40). — No. 95 (orig. ed. 69). — Nos. 99 and 100 (orig. ed. 56, 57), Prelude and Fugue.

J. Rheinberger, op. 78, No. 2; 3-voice; 3-Part Song-form; in Part II a brief auxiliary chromatic Motive is thematically treated (alone, per moto contrario, par. 158), and reappears in Part III, at times in conjunction with the Theme. Many more fine examples of the Fugue may be found in the Organ Sonatas of Rheinberger (and of other writers also).

Raff, Suite, op. 72, Finale; 3-voice; 3-Part Song-form; contrary motion freely used; also stretti and Augmentation; in Part III a new Counterpoint appears, which assumes considerable importance in subsequent episodes, and in the Coda.

Jadassohn, Preludes and Fugues for pianoforte, op. 56, Fugue 1; 4-voice; 2-Part form; stretto in 2nd Part. — Fugue 2; 3-voice; sectional; stretti and contrary motion. — Fugue 3; 3-voice; ditto. — Fugue 4; 4-voice; sectional; various effective Counterpoints, in successively accelerated rhythms. — Fugue 5; 4-voice; 2-Part form; much parallel movement in thirds and sixths. Some of these Fugues, and particularly those which follow, are quite strict in design and treatment: Fugue 6; 3-voice; sectional. — Fugue 7; 4-voice; sectional; stretti. — Fugue 8; 4-voice; sectional; animated Counterpoint in last Section. — Fugue 9; 5-voice; sectional.

Reinecke, op. 157, No. 4; Fugue; 4-voice; sectional form; Augm. in last Section.

An exceedingly interesting work, well worthy of most thorough scrutiny and analysis, is: Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue for Pianoforte, in b minor, by César Franck (ed. Litolff, 1578). The three numbers are coherent, and to some extent thematically inter-related; the chorale is original, and bears no relation to the traditional German church-melody; it occurs, rather episodically, during the Fugue, and even in brief (fragmentary) connection with the Theme (not as shown in par. 154); the Fugue is ostensibly 4-voice, but very free; an animated thematic Counterpoint appears in a later Section.

Émile Bernard, Prelude and Fugue in g minor, op. 14; 3-voice; 3-Part form.

149. The Concert-fugue seldom, if ever, appears as an isolated composition, but either as a movement of a larger work, or at least in company with an Introduction or Prelude.

The latter, as stated in par. 83a, may be connected thematically with the Fugue, or may be a totally separate piece, independent of the Fugue in every respect, excepting in key, which should be the same. Review par. 83a, thoroughly; and examine, again, the Preludes of Bach, Mendelssohn (op. 35, 37), and Rubinstein (op. 53).

EXERCISE 43.

Several examples of the Concert-fugue of various types, major and minor alternately. They may be written for Pianoforte (for two, or for four hands), or Organ.

N. B. Each Fugue must be preceded by an effective Prelude, polyphonic, semi-polyphonic, or homophonic, at option.

The Fugue for Other Instruments.

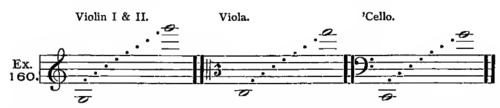

150. For String-quartet. The four instruments used are first and second Violin, Viola, and Violoncello. Their notation and average compass are as follows:

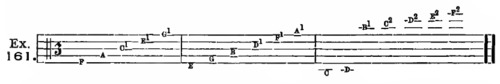

The Viola is written in a C-clef (the so-called Alto C-clef), and the student, if not yet familiar with it, should embrace this opportunity of learning it thoroughly. In performing this task, the student should adopt the following system: The C-clef should be learned by itself, and not by comparison with, or reference to, the G- or F-clefs. That is, the name of each line or space must be independently mastered. The clef-sign (  ) indicates the letter c 1 (the “middle” c of the pianoforte). Thus:

) indicates the letter c 1 (the “middle” c of the pianoforte). Thus:

After learning this perfectly, write familiar melodies or Themes in the new clef. Then read or play the Viola part alone of the String-quartets of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Then play, at the pianoforte, the String-trios of Beethoven, and afterwards the above-named quartets, slowly, and with less reference to the rhythm than to melody and general harmony. This being accomplished, the student may write a few fairly simple 4-part harmonizations of the chorales given in Exercise 26, upon the four staves of the String-quartet.

There is no essential difference between the Fugue for string-quartet and that for pianoforte, as regards the form and structural treatment. But the technique differs materially, because of the superior freedom and independence of the string-parts; hence, the parts may diverge, or cross, more freely. In a word, the constraint of keyboard technique is wholly removed.

For examples, see Haydn, String-quartets (Peters ed. 1026a), No. 6, D major, Finale — one-flat signature; 4-voice Fugue, Exposition only.

Mozart, String-quartets (Peters ed. 1037a), No. 1, G major, Finale; Exposition of one Theme at beginning, and of another 30 or 40 measures later.

Beethoven, String-quartets, op. 18, No. 4, Andante; a partial Exposition in first 19 measures. — Op. 59, No. 3, Finale; Exposition (irreg.) in first 40 measures or so.— Op. 131, whole of first movement. — Op. 95, second movement, meas. 34–64, and again later; Counterpoint retained. — Brahms, String-quintet, op. 88, portions of Finale.

151. The Fugue for Pianoforte and one or more Solo instruments (Violin, ’Cello, etc.) will derive its character and treatment from the technical nature of the instruments employed; but will be, in any case, more free and more effective than the pianoforte Fugue.

For examples, see Brahms, Sonata for pianoforte and ’cello, op. 38, Finale, first 53 measures, — and again further on.

Tschaikowsky, Trio op. 50 (a minor), 2nd movement, Var. VIII.

Bach, Sonatas for Clavichord and Violin, No. 1, 2nd movement. — No. 3, 2nd movement. — No. 4, 2nd movement. — No. 5, 2nd movement. — No. 6, 4th movement (Adagio). All very free; more like elaborate Inventions than Fugues.

The Vocal Fugue.

152. The constraint of technical treatment is most imperative in the Fugue for vocal parts. The compass of each voice must be respected, constantly and rigorously; awkward intervals, rhythms, or any other circumstances which impair the melodiousness and “singable-ness” of the several parts, must be scrupulously avoided; and good balance of effect (excluding wide spaces, though not an occasional crossing of the parts) must be preserved.

The form should be fairly definite (strict) and intelligible. Episodes are necessary, but they must be of a more sober character than in the instrumental Fugue, and must be held well within the general thematic atmosphere of the Subject. Particular attention should be directed to the uppermost voice, which is mainly responsible for the clear and effective melodic form of the whole.

The Theme should always be a striking setting of some brief, pregnant text-sentence, — melodious, but rhythmically characteristic, — and it accompanies the same words throughout. The voices not occupied with the Theme, however, are generally written without regard to the text, — the latter being subsequently adjusted to the finished tones, with strict regard to grammatical sense and order, and to the correct prosodic disposition of accented and unaccented syllables and words.

Rests are indispensable; short ones for breathing, and occasional protracted silence (especially before an announcement of the Theme) for variety and contrast.

153. If, as is almost invariably the case, the Vocal fugue is to be accompanied, the instrument chosen (pianoforte or organ) may either be limited (1) to an exact duplication of the parts, unisono; or (2) may double either outer part, especially the Bass, in octaves, perhaps adding an occasional full chord to support the vocal parts where their effect is somewhat meagre; or (3) the accompaniment may add materially to the bulk, or to the rhythmic movement (or both), of the vocal parts,—even to the extent of introducing independent imitations and announcements of the Theme. Further, the accompaniment may provide a brief instrumental Introduction, occasional Interludes, and a Postlude, if necessary or desirable.

See Bach, “B-minor Mass,” No. 6; Gratias agimus, 4-voice; Accompaniment simple. Compare No. 24. — No. 3, Kyrie, 4-voice.—No. 1, Kyrie, 5-voice: thematic instrumental Prelude and Interlude; large 2-Part Form. — No. 13, Patrem omnipotentem, 4-voice; partly harmonic Accompaniment, otherwise elaborate. — No. 12, Credo in unum Deum; 5-voice; Running Bass in Accompaniment.

Mendelssohn, “St. Paul,” No. 29, Is this He? — simple Fugue, with homophonic Interlude, derived from the Counterpoint to Theme. — No. 43, See what love; irregular Exposition. — No. 15, Behold now total darkness; Running Accompaniment, chiefly Soprano.

Haydn, “The Creation,” No. 11, For He both heav’n and earth; Accompaniment elaborated. — No. 29, We praise Thee now, Running Accompaniment (figural).

Händel, “Messiah,” No. 26, He trusteth in God. — No. 6, And He shall purify; free, somewhat irregular; homophonic episodes. — No. 37, And their words; Exposition irreg. (Response, Response, Subject, Subject). — No. 52, Amen; an Exposition, Interlude, and long episodic passages, with fragments of Theme.

Händel, “Judas Maccabaeus,” No. 26, 2nd Part, Where warlike Judas; Exposition irreg. (4 “Subject “-announcements).

Mozart, “Requiem,” No. 8, Quam olim; independent Accompaniment, quasi harmonic.

Cherubini, “Missa solemnis” (in D), Kyrie eleison (Allegro moderato); Accompaniment partly harmonic, partly running rhythm, and partly single duplication. — Dona nobis pacem; observe different forms of accompaniment.

Mendelssohn, “Elijah,” No. 1, The harvest now is over; effective Imitation (echo) of last member of Theme; brief harmonic episode. — No. 22, Though thousands languish; Accompaniment partly harmonic. — No. 29, Shouldst thou, walking in grief. — Final chorus, Lord, our Creator.

Händel, “Israel in Egypt,” No. 4, They loathed to drink. — No. 10, He brought them out with silver and gold. — No. 16, And believed the Lord; homophonic episodes. — No. 18, I will sing, and For He hath triumphed; two Themes in fairly regular alternation, — not together (comp. par. 52). — No. 26, Thou sentest forth Thy wrath. — No. 13, He led them through the deep (Double-chorus, 4- to 8-voice texture); characteristic Counterpoint, thematic (quasi “Double”). — Etc.

Brahms, “German Requiem,” No. III, final tempo (Der Gerechten Seelen — The souls of the righteous); the entire Fugue rests upon a persistent Tonic organ-point.— No. VI, final tempo (Herr, Du bist würdig — Thou art worthy); powerful thematic episodes; variety of Counterpoints. Brahms, Motet, op. 29, No. II; 2nd movement and Finale.

Horatio W. Parker, “Hora Novissima,” No. 4, Pars mea, Rex meus. — No. 10, Urbs Syon unica (unaccompanied). — No. 11, quartet, Urbs Syon inclyta; Subject of unusual length, 11 measures (cited again in par. 189). — H. W. Parker, “St. Christopher,” Act III, Scene 2, Quoniam Tu solus sanctus (Contrary motion; Augmentation).

Beethoven, “Mass in C,” op. 85, Cum sancto spiritu; simple Exposition; Interlude, chiefly harmonic; new Exposition with chromatic Counterpoint.— Et vitam venturi; instrumental Interludes, and vocal Soli. — Osanna in excelsis.

Beethoven, “Mass in D,” op. 123, In gloria Dei patris, Amen; elaborate; Counterpoint retained through the Exposition; partly double-quartet. — Osanna in excelsis (both versions).

Verdi, “Falstaff,” Finale, Tutto nel mondo è burla; large chorus, but practically 4-voice; Counterpoint retained during first section, and used later episodically; frequent contrary motion.

EXERCISE 44.

A. Two Fugues (each with brief Introduction, or Prelude) for String-quartet, — major and minor; different measure and tempo for each.

B. A Fugue, with Prelude, for Pianoforte and Violin.

C. Two or more Fugues for mixed quartet (or chorus), with organ or pianoforte accompaniment. The text may be taken from any of the above examples, or from any part of the Bible.

Fugue in Connection with Chorale.

154. Fugue with Chorale. This form corresponds in design exactly to the Invention with Chorale, but differs from the latter in that greater degree of seriousness and strictness which distinguishes the Fugue in general from the Invention. All the specific directions are given in paragraphs 99 to [par.] 105, which must be thoroughly reviewed.

The introductory measures (par. 100d) are usually a regular Exposition (par. 121, etc.), during the later course of which the chorale melody appears, in the part left vacant for the purpose. Thereafter the form is that of the ordinary sectional Fugue, into the texture of which the chorale Lines are successively interwoven, apparently as incidental addition, — though naturally they influence (or even dictate) the progressive development.

The Subject is almost invariably evolved out of the first Line of the chorale, with more or less freedom.

Analyze minutely: Bach, Organ Comp. (Peters compl. ed.), Vol. VI, No. 30; 3-voice; Cantus firmus in Bass; long Theme, independent of the chorale, with two very quaint modifications. — Vol. VII, No. 39a; 4-voice; c.f. in Soprano; Theme derived from first two Lines of chorale; a. stretto-Imitation, with which the Fugue begins (after two beats, in the 5th), recurs frequently; other stretti, and contrary motion, also appear. This is an extremely interesting and instructive example. Compare it carefully with the next, Vol. VII, No. 39b, which it closely resembles in all essential respects; 4-voice; c.f. in Tenor.

Guilmant, Organ Sonata, Op. 80, Finale.

Mendelssohn, “St. Paul,” No. 36, But our God; 5-voice; chorale in 2nd Soprano; two Themes, in fairly regular alternate Sections, both independent of the chorale.

155. Chorale as Fugue-group. This is the parallel form of the chorale as Invention-group, explained in par. 106, which review thoroughly.

Out of each successive Line of the chorale a Subject is evolved; each Subject in turn is carried strictly through the parts, as Exposition, in which the chorale finally participates, as usual. Thus the whole constitutes a group or chain of Fugues (or Fugue-Expositions, — Fughettas), corresponding to the number of Lines in the chorale.

See Bach, Organ Comp., Vol. VI, No. 21; 4-voice; c.f. in Soprano, each time as last announcement of the Theme. — Vol. VI, No. 28; 4-voice; c.f. in Soprano, as Augmentation of Theme.—Vol. VII, No. 37; 4-voice; c.f. in Soprano, somewhat embellished, and each time as last announcement of the Theme; a new (10th) Motive for the Coda, in animated rhythm. — Vol. VII, No. 50; 4-voice; the last announcement of Theme each time in Bass, as Cantus firmus. — Vol. VII, No. 55; 4-voice; the Pedal is added as duplication of the Bass at end of each Exposition, to emphasize the c.f. — Vol. VI, No. 13; 6-voice; c.f. in 1st Bass, as Augmentation of the Theme; several thematic Counterpoints. — Brahms, Chorale-Vorspiele, op. 122, No. 1.— Brahms, Motet, op. 29, No. 1; 5-voice; c.f. in 1st Bass.

156. The Chorale-Fugue. Somewhat allied to the Chorale-Invention, par. 110, which review. The Subject, or Subjects, are derived from the first, or later, Lines of the chorale, and manipulated in the usual manner. But the chorale-melody, as such, is absent.

See Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. VI, No. 33; 4-voice; many stretti; two auxiliary, or episodic, Motives. — Vol. VI, No. 1 1; 3-voice; thematic Counterpoint in later Sections. — Vol. VI, No. 20; 4-voice; special design. — Vol. VII, No. 41; 4- to 5-voice; secondary Motive, derived from Counterpoint. — Vol. VII, No. 60; 4-voice; basso ostinato in Pedal (transposed recurrences); thematic Counterpoints.

A smaller variety, the Chorale-Fughetta, is illustrated in the following:

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. V, No. 20; 3-voice. — Vol. V, No. 43, 3-voice. — Vol. VII, No. 61; 3-voice. — Vol. VII, No. 40c; 4-voice; Exposition in stretto. — Vol. VII, No. 54; 3-voice; the Subject, and two secondary Motives, are derived from three Lines of the chorale; Line 4 is intimated by the descending scale, constantly present in the Counterpoints.

The Group- (or Motet-) Fugue.

157. The Fugue-group is similar to the form described in par. 155) but is usually broader in design, and by no means necessarily identified with the chorale. Different Subjects — usually, though not necessarily, of similar character (and perhaps related in contents) — are successively, sometimes alternately, manipulated as separate complete Fugues (or Fughettas), more or less extensively and independently.

See Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. III, Fugue 6; 4-voice; large 3-Part form; the first Subject is the basis of Part I; a totally different Subject (chromatic) is manipulated in Part II, as separate Fugue, so to speak; in Part III the first Subject is resumed; this Part is a nearly exact recurrence of the first Section of Part I, abbreviated at the beginning, and extended at the end. — Vol. III, Fugue 7; 4-voice; the first Division is a Double-fugue (to be analyzed later); the second Division is a brief Interlude (free, similar to the Prelude to the whole number); the third Division is based upon a rhythmically modified Augmentation of the first measure of the preceding Fugue-subject; animated rhythmic Counterpoints in later course. — Vol. III, Fugue 9; 4-voice; interjoined with the Praeludium (meas. 1–39); Division I is a Double-fugue (see later), to meas. 62; Division II has a different Theme, though somewhat related to the preceding; an independent Coda, similar to the Introduction, is added.— Vol. VI, No. 10; Chorale-fugue (chorale itself absent), in group-form; 3-voice; three sections; two different Subjects alternating (returning to first). — Vol. VI, No. 34; ditto; 4-voice; 5 Themes (or Motives, — quasi Invention-group).

Bach, “B-minor Mass,” No. 19, last Division (Vivace e allegro), Et expecto and Amen; 4 Themes.

Mendelssohn, “St Paul,” No. 23, For all the Gentiles, and Now are made manifest; 5-voice; large 3-Part form, quasi Song with Trio. — No. 20, The Lord He is good, and For His word; successive Expositions, and then close alternate treatment (not “Double-fugue”). — Final chorus, Bless thou the Lord, and All ye His angels; 4-voice; two Subjects.

EXERCISE 45.

A. One or two examples of the Fugue with Chorale (par. 154).

B. One or two examples of the Chorale as Fugue-group (par. 155).

C. An example of the Chorale-Fugue (par. 156).

D. One or two examples of the Fugue-group (par. 157). To each of the latter a Prelude, or free Introduction, is to be prefixed.

Irregular Fugue-Species

158. The Fugue in Contrary motion (per moto contrario). In this species the first and third Imitations of the Theme are made in Contrary motion, so that the 4-voice Exposition consists of the alternate “regular” and “contrary” motion (the latter standing each time for the usual “Response”). This arrangement may extend through the entire Fugue; or it may be confined wholly (or nearly) to the Exposition; and, further, the alternation may be more or less irregular (for instance, in the Exposition, or later, the regular motion twice, followed by the contrary motion twice; etc.).

The relation of the contrary motion to the original form of the Theme is generally that defined in par. 29a, particularly Ex. 72, which review. See also Exs. 73 and [ex.] 74. The Theme in contrary motion may be announced in the original key, or, as usual, in the Dominant key (by simple transposition to the upper 5th or lower 4th).

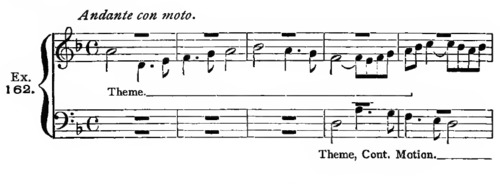

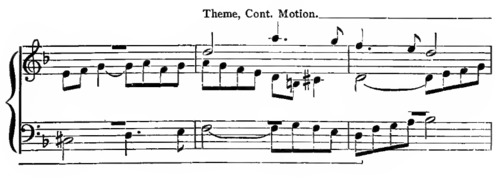

Analyze, thoroughly, Bach, “The Art of Fugue,” Fugue No. 5. The Exposition runs as follows:

Six measures later (in meas. 17) the Exposition closes, with a vague cadence. The Fugue has a Special Design, extending through 5 Sections; Sec. II (meas. 17–33) is very similar to the preceding one; Sec. III (meas. 33–46) is based upon a stretto in contrary motion; Sec. IV (meas. 47–65) upon a stretto in parallel motion, after one and one-half measures; Sec. V (to meas. 86) upon a parallel stretto, after one measure. The Coda (last 5 measures) is based upon a simultaneous (or double) announcement, in regular and contrary motion. — “Art of Fugue,” Fugue No. 13; 3-voice; per moto contrario, absolutely regular alternation; frequent episodes, all similar; cadences vague. The following number (13b) is the exact contrary motion, and partial Inversion, of the preceding. — “Art of Fugue,” two Fugues for 2 pianofortes; both 4-voice, and per moto contrario; the Fugues are different manipulations of the same Subject. Compare them minutely.

Brahms, Fugue in a♭ minor for Organ, first 27 measures; 4-voice; Counterpoint retained, in regular and contrary motion.

Händel, “Israel in Egypt,” No.11, Egypt was glad, first 30 measures; 4-voice; the Dominant (b in e minor) is answered by the Tonic (e), in the first “Response”; the two following announcements are both in the original motion; later the alternation is more regular.

Mendelssohn, “Elijah,” No. 16, The flames consume; Exposition in contrary motion.

Beethoven, String-quartet, op. 127, Scherzando vivace; Exposition in contrary motion (“fugato,” — i.e, in fugal style, imitatory, but not exactly a Fugue).

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. VII, No. 39c; Fugue per moto contrario, with Chorale; 5-voice; Cantus firmus in Bass; stretto-imitations throughout.

159. The Fugue in Augmentation, or in Diminution. In this species, which is very similar to the above, the Augmentation, or Diminution, of the Subject is substituted for the contrary motion; or, in rare instances, is combined with the latter.

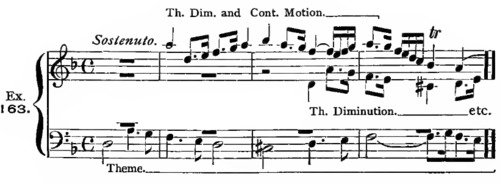

See Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Fugue No. 6; this is a 4-voice Fugue in “Diminution and Contrary motion”; probably 3 Sections and Coda; the Exposition begins thus:

“Art of Fugue,” Fugue No. 7; 4-voice Fugue in “Augmentation and Contrary motion”; contains also a series of Double-augmentations, and fragments of the Diminution (end of 7th measure, in Soprano); cadences very vague; the form is either simply one broad section, constituting the Exposition of the Double-augmentation, through the four parts (Bass, Tenor, Alto, Soprano, alternately in contrary and regular motion); or it contains four Sections, with one announcement of the Double-augmentation in each.

Händel, “Messiah,” No. 33, Let all the angels; Fugue in Augmentation.

160. The Fantasia-fugue. This somewhat contradictory term maybe justified in the case of those Fugues which begin seriously, and contain a more or less legitimate Exposition, but thereafter degenerate into a free, fantastic series of sections or sentences (passages), based upon fragments only of the Theme, possibly in distorted forms.

A beautiful and entirely defensible illustration occurs in Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 3; it is 3-voice, sectional form; the Exposition is in stretto, and Contrary motion (Subject in Bass, 1½ measure), ending in meas. 7; in Sec II (meas. 7–11) the 2nd half of the Theme is reconstructed; Sec. III (meas. 11–14) is episodic; Sec. IV (meas. 14–17) reverts to the original form of the Theme; the last Section (meas. 17 to the end) does not contain the original Theme entire, but is one long episode, or Fantasia (18 measures), in which intimations of the Diminution, Augmentation, and a unique mixture of other thematic fragments occur. — See also Bach, Clav. Comp., Peters ed. 216, No. 6, “Capriccio”; the purpose is evidently that of a Fugue, but the extensive episodic passages (quasi homophonic figuration), and the general treatment, make the title “capriccio” more appropriate.

Kindred forms are (1) the Recitative-fugue:

See Mendelssohn, Pfte. Sonata, op. 6, Adagio movement; no definite measure; 4- to 5-voice; large 2-Part form, with a homophonic (lyric) section as Interlude, and Postlude, in  time.

time.

and (2) the Harmonic fugue, i.e., a fugal thematic design, but of marked harmonic character, or with distinctly harmonic auxiliary parts.

See Schumann, op. 32, No. 4, “Fughetta.” — Bach, Clav. Comp., Peters ed. 211, No. 3.

EXERCISE 46.

One example each of the Fugue in Contrary motion (par. 158), and the Fugue in Augmentation, — or in Diminution, at option, — (par. 159).