CHAPTER XII.

The Four-Voice Fugue. — The Exposition.

121. The Exposition or first Section of a Fugue contains as many announcements of the Theme (Subject and Response alternately — par. 114) as there are parts employed. In the 4-voice Fugue the order is, therefore (when regular), Subject, Response, Subject, Response.

a. The first Response may begin simultaneously with the final tone of the Subject (Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 8). Or immediately after the Subject ends (Vol. I, Fugue 6). Or still a little later, so that one or more tones must be added to the Subject, as intervening figure (Vol. I, Fugue 1, one intervening tone; Vol. I, Fugue 2, ditto; Vol. I, Fugue 12, two intermediate tones; Fugue 11, three tones; Fugue 3, four tones; Fugue 7, seven tones, — more than this number could scarcely be justified). Or, more rarely, the Response may enter before the cadence tone of the Subject, as brief stretto (Vol. I, Fugue 9; the Response overlaps the Subject one beat, possibly three, — the length of Subject is somewhat uncertain).

b. In the third of these possible cases, where intermediate tones are used, the latter must be carefully chosen, in keeping with the conduct of the Subject, and with a view to their subsequent employment as thematic basis of the episodic passages (as in Vol. I, Fugue 7).

122. The first counterpoint — that which follows the Subject in the same part, as contrapuntal associate of the Response — is sometimes called the “Counter-subject”; as this term is misleading (in the Single Fugue), it will be spoken of here simply as the “Counterpoint.” Comp. par. 34.

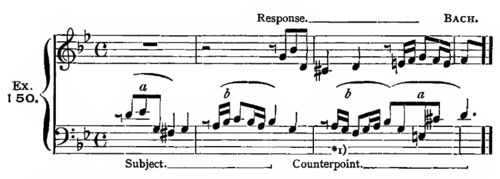

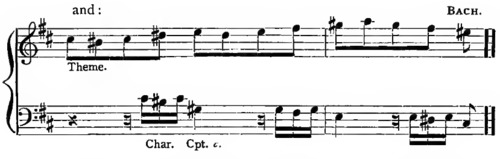

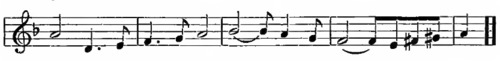

It is a very important factor in the Fugue (or may become so), and especial pains must, therefore, be taken with its formation. It may be derived from the figures of the Subject itself:

*1) Both of these figures of the Counterpoint are derived from those of the Subject, in contrary motion. See also Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 5.

Or the Counterpoint may be more or less independent of the Theme, its conduct being governed by the general conditions of good contrapuntal association.

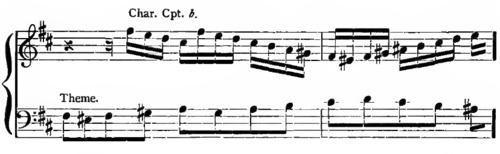

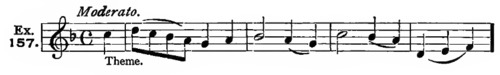

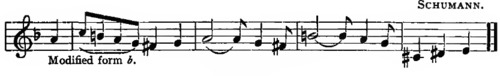

Or it may assume a characteristic rhythmic or melodic form, in intentional opposition to the current of the Response, or as a wholly individual factor of the entire Fugue. Thus:

*1) The Counterpoint is admirably individualized by the line of sequences. See further, Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 18, similar; Vol. I, Fugue 2— rhythmic contrast with the Theme; Vol. I, Fugue 12; Vol. II, Fugues 10, 11, 16, 20 (rhythmic), 22 (chromatic).

In any case, but especially in the last mentioned, the first Counterpoint is more than likely to reappear from time to time in connection with later announcements of the Theme, as part of the thematic material of the composition; and this possible use must be kept in mind, and must emphasize the thoughtfulness and strictness of technique with which the Counterpoint is to be devised. It is well to make several experiments, in various styles, and choose the most promising version.

EXERCISE 36.

A. Examine the formation of the first Counterpoint in every Fugue of the Well-temp. Clavichord.

B. Write, upon one or two staves at option, each of the Subjects of the preceding Exercise, in the most convenient register, followed by the Response in the next higher or next lower part, and add the Counterpoint (as in Exs. 150, [ex.] 151). Each Subject is to be manipulated twice, — with the Response respectively above and below.

123. These and the succeeding announcements of the Theme, during the regular Exposition, are determined by the following formula:

- Subject, — in either one of the four parts;

- Response, — invariably in the next higher or next lower part;

- Subject, — in the parallel part to that in which the Subject first appeared, an octave higher or lower than the former announcement;

- Response, — in the remaining part, i.e., the parallel to the part in which the first Response appeared, and an octave higher or lower than the latter.

In other words, the Subjects appear in parallel parts, and the Responses, likewise, in the other parallel pair of parts.

N. B. Parallel parts are those which are separated by one part, namely, Soprano and Tenor, Bass and Alto.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 5: Bass, Tenor, Alto, Soprano.

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 17: Tenor, Bass, Soprano, Alto.

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 18: Tenor, Alto, Soprano, Bass.

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 20: Alto, Soprano, Bass, Tenor. Beginning with Soprano, the order would be: Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass.

124. In some, comparatively rare, instances the Exposition is irregular, for some valid reason, and in one of the following respects:

(1) The order of the parts;

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, No. 1, — the order is, Alto, Soprano, Tenor, Bass, instead of Alto, Soprano, Bass, Tenor; i.e., the 3rd announcement is not in the parallel of the first part.

(2) The alternation of Subject and Response;

See, again, Fugue 1, Vol. I; the order is Subject, Response, Response, Subject (the second announcement of the Subject is in the parallel of the first part, but occurs too late — as fourth voice). See also Vol. I, Fugue 12; Subject, Response, Subject, Subject, in Tenor, Alto, Bass, Soprano. — Vol. I, Fugue 14; Vol. II, Fugue 17.

(3) The number of announcements, which may be more (very rarely less) than the total number of parts.

The “extra” announcement is rare in the 4-voice Fugue, though common in the 3-voice. See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 17; the Exposition is irregular, as already seen; and a 5th announcement (“Subject”) is added in Bass, meas. 13–15. Vol. II, Fugue 23, extra announcement (Bass), in meas. 19–22. Bach, Org. Comp. (Peters compl. ed.), Vol. II, Fugue 3, extra announcement, somewhat abbreviated, in Bass, meas. 45–49. Vol. IV, Fugue 2.

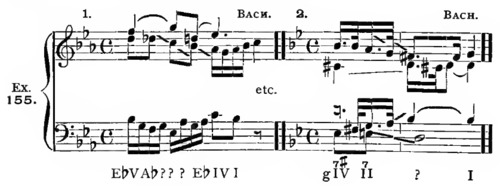

125. a. After the first Response (second announcement of the Theme), an episodic interlude of one or more measures is generally inserted, partly by way of variety, but chiefly as a means of modulating back into the original key, and preparing for the next announcement of the Subject. The episode must, of course, be strictly in keeping with what precedes, and is usually derived directly from it. Review par. 41b. For illustration, Ex. 150 continues thus:

See further, Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 14, meas. 7 (derived from end of meas. 2); Fugue 17, meas. 3–4 (sequences in Bass, followed by modified form of the Counterpoint); Vol. II, Fugue 5, meas. 4; Fugue 7, meas. 13; Fugue 22, meas. 9–10.

In Vol. I, Fugue 18, there is no episode before the second announcement of the Subject; and the same in Vol. I, Fugue 23, and Vol. II, Fugue 9.

In Vol. I, Fugue 5, the episode is made of new material, but rhythmically related to what precedes.

Vol. I, Fugue 20, meas. 7, new figure (scale-line); Vol. I, Fugue 22, meas. 6–9, new, but closely related to the foregoing; rhythm curiously shifted (a figure of 6 beats in a 4 beat measure).

Vol. II, Fugue 8, meas. 5–6; new, but partly derived from Subject.

b. As a rule, there is no further episodic interlude (in the 4-voice Fugue) before the last (4th) announcement of the Theme, — the last Response. But when the latter is finished, an episode, more or less lengthy, is almost obligatory, as a means of establishing the key in which, at this juncture, the Exposition is expected to close. It is during this final episodic passage that an extra (5th) announcement of the Theme (as “Subject,” probably) may occur. See par. 124 (3).

126. The Exposition ends, as a rule, with a perfect cadence in the Dominant key (from a major beginning), or in the Relative key (from a minor beginning). Other keys, especially the original key itself, are possible, however, and not infrequently chosen. The perfect cadence is often (perhaps most commonly) made fairly strong, by the emphatic succession V–I in Bass, Tonic in Soprano, on an accented beat. But sometimes it is much lighter; and occasionally it is so transient and indefinite that the actual close of the Exposition can be defined in a general way only, or not at all. In no case, however, no matter how strong the harmonic form of the cadence may be, is any decided check of the rhythmic movement permissible. Review par. 40h.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 23; the Exposition ends in meas. 9, firmly, on the I of the Dominant key; there are no episodes at all.

Vol. I, Fugue 5, meas. 6, cadence in Dominant key, fairly firm; no second episode.

Vol. I, Fugue 16, meas. 12, firm perfect cadence in Relative key; second episode, meas. 8–12, designed like the first one.

Vol. I, Fugue 17, meas. 7 (2nd beat), or meas. 10 — probably the latter, but very indefinite in either case.

Vol. I, Fugue 18, meas. 11, cadence in Dominant key from minor beginning.

Vol. I, Fugue 20, meas. 14, ditto; by altering the chord-3rd (g) to g♯, the I of the Dominant key is changed, in a characteristically abrupt manner, into the V of the original key.

Vol. II, Fugue 5, meas. 10; light Dominant cadence.

Vol. II, Fugue 7, meas. 30; strong Dominant cadence.

Vol. II, Fugue 8, probably meas. 11; very vague.

Vol. II, Fugue 9, meas. 9; Dominant cadence, 3rd in Soprano.

Further, Vol. I, Fugue 1; Exposition irregular; ends in meas. 7, with light Tonic cadence.

Vol. I, Fugue 14; Exposition irregular; ends in meas. 20, with firm Dominant cadence (from minor beginning).

The Fughetta.

127. The Fughetta is a small Fugue, containing no more than one Section (the Exposition, possibly extended by one or two extra announcements of the Theme); or perhaps two Sections, — the Exposition and one additional Section. In the first of these cases, the Exposition must terminate with a strong perfect cadence in the original key.

Bach, Air with 30 Var. (Clav.), Var. 10; two “Parts” or Sections.

Bach, Organ Comp. (Peters ed.), Vol V, No. 7; No. 18 (irregular Exposition, two Sections).

Schumann, “Fughettas” for pianoforte, op. 126; No. 2 (two Sections, very vague cadence; begins with “Response “); No. 3 (three Sections, cadences vague); No. 4, ditto; No. 5, ditto (new, characteristic counterpoint in Sec. III); No. 7 (three Sections, cadences fairly clear, stretti in Sec. III). These are all scarcely more than elaborate Inventions.

EXERCISE 37.

A. Write several examples of the Exposition of the 4-voice Fugue, using some of the Subjects of the preceding Exercises. Employ major and minor Subjects alternately, and different rhythmic styles and tempi.

B. Write two or three examples of the complete 4-voice Fughetta of one Section; i.e., an Exposition closing with perfect cadence in the original key.

The Sectional Form.

128. The Exposition (first Section) is an essential and characteristic factor of this form of composition, appearing in every genuine Fugue, no matter what its subsequent development (its design as a whole) may be.

That which follows the Exposition, however, is not (as a rule) subject to any further specific conditions, — excepting such as may be involved in some “special design” of the Fugue as a whole (to be considered further on). The constraint of special rules is relaxed; in the second Section, and other following ones, it does not matter how often the Theme appears, in which parts, nor on which scale-steps. The subsequent conduct of the Fugue may be as free as that of the Invention, always excepting that a certain dignity and general seriousness of style should be maintained. After the Exposition the writer is free to realize more definite structural purposes; to carry out more extensive modulatory designs; to develop the thematic resources of the subject, both as a whole, and in its component figures; and to pursue some broad (quasi dramatic) design, leading in successive stages to effective climaxes, at, or near, the end.

129. The most convenient and common design for the Fugue is the simple Sectional form; for this provides the most natural means for the simple progressive development of the resources of the Theme. Review par. 39.

The number of sections is optional (from 3 to 6 or 8). Their cadences, and the modulatory design of the whole, correspond to the directions given for the Invention.

130. a. The second Section may begin with an announcement of the Theme, in any part, and in any next-related key, preferably the one in which the Exposition closed.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 16 (meas. 12); Fugue 18 (meas. 11).

And, as already stated, this section, and all which follow, may contain as few or as many successive announcements as appears convenient or desirable, — as a rule, however, not in the same part twice in immediate succession.

b. Or the Section may begin with a carefully planned Episode. This seems to be the best and most common practice.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 5 (meas. 6, — episode derived from Theme).

Vol. I, Fugue 23 (meas. 9–11; derived, with quaint rhythmic modification, from Theme, and containing frequent allusions to the first figure of the Counterpoint,— descending scale).

Bach, Org. Comp. (Peters ed.), Vol. II, Fugue 1 (meas. 19–28, derived from Theme).

Vol. II, Fugue 2 (meas. 17–26).

c. Such an episode is likely to acquire a certain independent importance in the Fugue, and to reappear, in the same section or in later ones, — not literally, but in the same general thematic form; in different keys, naturally, and in various inversions. This is the case with the episodic passages in general.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. 1, Fugue 17; the episode in meas. 11 (with sequence in following measure) reappears in meas. 14, 15, and 19, 20, each time in a different key, and with inverted parts. Also Vol. I, Fugue 14; similar episodes in meas. 7, 18, and 28.

These recurrences of the episodic material not only institute well-defined variety (as opposed to the thematic announcements), but contribute to the unity and definite form of the whole. In some instances, especially in the broader organ fugues of Bach, the episodes assume an importance fully equal, if not superior, to that of the thematic portions, and lend (by their frequency, extent, and characteristic treatment) a very effective physiognomy to both form and contents.

See, for example; Bach, Org. Comp. (Peters ed.), Vol. III, Fugue 3; the episodes are constructed, throughout, in very similar fashion upon an auxiliary motive (derived from a figure of the Counterpoint); they appear in meas. 15–17, 25–28, 36–42, 50–56, 64–66 (new episode), 67–70, 78–80, 88–100, 108–114, etc., etc. Also Vol. II, Fugue 4; episodes after nearly every announcement of the Theme: meas. 7–9, 12–14, 18–21, 28, 32–36, 39–43, 47–50, 54, 57–65, 68–79 (similar to preceding one), 82–93 (ditto), 97–100 (like 47–50), 106–109 (like 32–36).

131. Each succeeding Section of the Fugue may (perhaps should) contain some new traits, — most naturally, new “Counterpoints” to the Theme. And each Section should be more interesting and effective than those which preceded. Therefore it is customary to introduce the contrary motion of the Theme, in later Sections; and, near the end, good stretto-imitations are desirable. Review, very thoroughly, par. 33 (Ex. 83).

Analyze, very minutely, the following Fugues from the Well-temp. Cl. of Bach:

Vol. I, Fugue 23; Section II begins in meas. 9, with episode, followed by one announcement of Theme (Tenor); Sec. III begins in meas. 13, with same episode, followed by Theme in Alto; Sec. IV begins in meas. 18, with Theme in contrary motion (Soprano), followed by same in Alto, then original motion in Bass and in Tenor; Sec. V begins in meas. 26, with former episode, followed by Theme in Alto, and then in Soprano.

Vol. I, Fugue 16; Sec. II begins in meas. 12, with impressive solo-announcement of Theme, — further, Theme in Bass, Soprano, then Bass and (2 beats later) Alto in stretto; the Alto Theme extends partly over into Sec. III, which begins in meas. 18, and contains Theme in Bass, Soprano, and Alto; this section closes, peculiarly, with a firm perfect cadence in the principal key; Sec. IV is exclusively episodic, and seems to be a Retransition, leading back to the beginning, — intimating (in connection with other traits) that this Fugue is designed in the 3-Part Song-form (par. 136); Sec. V begins in meas. 28, with a stretto of the Theme in Alto, Tenor, and Bass (the latter only fragmentary), followed, after an episode, by Theme in Alto (meas. 31), and, finally, in Tenor.

In Vol. II, Fugue 5, the stretto-design is more elaborate. Analyze minutely. There are eight sufficiently definite sections; in Sec. V (meas. 27) a 2-voice stretto appears; in Sec. VI (meas. 33) a 3-voice stretto; and in Sec. VIII (meas. 44) a 4-voice stretto.

In Vol. II, Fugue 8, there is a double-announcement of the Theme in simultaneous original and contrary motion, in Soprano and Tenor, in the Codetta (last four measures).

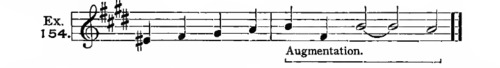

In Vol. I, Fugue 5, there is a definite and characteristic arrangement of episodic passages; Sec. III begins (in meas. 9) with an almost homophonic episode, derived, by Augmentation, from the Theme, and continued during two measures; it recurs at the beginning of Sec. IV (meas. 17) inverted, and extended to three measures; and again in meas. 21 in the original form.

See further, Bach, Org. Comp. (Peters ed.), Vol. II, Fugue I; Sec. II begins in meas. 19, with an episode, followed by Theme in Tenor; Sec. III begins in meas. 35 with Theme and characteristic (new) Counterpoint; Sec. IV, in meas. 55 with new episode; Sec. V, in meas. 85 with remainder of Theme announced in preceding measure (Tenor). These sections are considerably longer than in the Fugues of the Well-temp. Clavichord.

Also Vol. IV, Fugue 2; the Exposition contains an extra (5th) announcement, in meas. 28; Sec. 2 begins in meas. 34 (cadence light) with an episode; then Theme in Alto, episode, Theme in Tenor, episode, Theme in Soprano, episode, Theme in Bass; Sec. III begins in meas. 71, with a long episode (to meas. 83); Sec. IV, in meas. 105, with remainder of Theme in Alto, and closes in meas. 132; from there to end, Coda. The first Counterpoint is retained approximately, throughout (par. 132). The episodes alternate almost regularly with the thematic announcements.

132. As intimated above, it is quite common to retain the first Counterpoint, and to use it more or less constantly with later announcements of the Theme. This retention of the “Counterpoint” is not, however, to be too persistent in the “Single” Fugue, — such constant recurrence of a contrapuntal associate being a distinctive condition of the “Double-fugue,” as will be seen.

It may be retained during the Exposition only; perhaps recurring from time to time in later sections; or it may be abandoned after the first Response, and recur later; it may be used entire, or in part; and may be modified to any extent.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 14; Subject in Tenor, Response in Alto; during the latter a characteristic Counterpoint is carried by the Tenor; it recurs in Alto (meas. 8–10) against Theme in Bass, extended at the beginning by an anticipation of the first figure; it recurs again in Bass (meas. 15–17) against Theme in Soprano, with the same introductory extension; and again in Alto (meas. 25–27), in Soprano (meas. 29–31), and, somewhat modified, in Alto (meas. 37–39). This retention of the Counterpoint is almost as persistent as in the Double-fugue.

Vol. I, Fugue 23; the Counterpoint lies first in the Tenor (meas. 3–4, — beginning with the characteristic descending scale, out of which, by the way, all the episodes are largely constructed); it recurs in Alto (meas. 5–6), and in Soprano (meas. 7–8), — that is, it is retained during the Exposition. But it does not occur again (save as occasional fragmentary allusion) until near the end (in Alto, meas. 31–32), against the Theme in Soprano.

Vol. II, Fugue 8; the Counterpoint is characteristic, consisting of 4 sequential figures (Ex. 151); it recurs at each following announcement of the Theme, in Tenor (meas. 7–8), Bass (meas. 9–10), Soprano (meas. 15–16). Then it is once absent, reappearing next in Bass (meas. 19–20), and in Tenor (meas. 21–22). It then disappears altogether.

In Vol. II, Fugue 9, the Counterpoint runs thus:

It occurs in Bass (meas. 3), recurs in Tenor (meas. 4–5), and Alto (meas. 6). It reappears episodically (without the Theme) in Tenor (meas. 8). In meas. 11–12 it appears, somewhat modified, in Tenor; and immediately afterward in Soprano, curiously modified thus,

in which form it is at once carried through the four parts, episodically, as stretto after a half-measure (Soprano, Alto, Bass, Tenor). It reappears in its original form in Soprano (meas. 36), Alto (37), and Tenor (38), — the last time extended sequentially.

Vol. II, Fugue 22; the Counterpoint is largely chromatic, occurring first in Alto (meas. 5–8), then again in Alto (meas. 11–14), then in Bass (meas. 17–20). When the Theme appears, later, in contrary motion, the Counterpoint, also in contrary motion, again accompanies it: Alto, meas. 42–44; Tenor, meas. 46–48; Alto again, 52–54; and a fragment in Soprano, meas. 59–60.

Vol. II, Fugue 23; a very striking Counterpoint is retained throughout the Exposition only; Bass, meas, 5–8; Tenor, meas. 10–13; Alto, meas. 14–17; Soprano, meas. 19–21. It is absent during the remainder of the Fugue (which, as a whole, will be cited again as a “Double-fugue “).

EXERCISE 38.

A. Analyze, very minutely:

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 18.

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugues 5, 8.

Bach, Org. Comp. (Peters ed.), Vol. II, Fugue 1; Fugue 3 (seven sections; Counterpoint retained nearly throughout, — absent in Sec. V and part of Sec. VI; one stretto in Sec. VI).

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. III, Fugue 5 (various Counterpoints; many episodes).

Bach, Clavichord works, Peters ed. 212, No. 4 (p. 66).

B. Write a number of complete 4-voice Fugues (at least two) in Sectional form. Both major and minor. Different species of measure, and different character and tempo, to be adopted for each example.

Additional Miscellaneous Directions.

133. Review, thoroughly, par. 41a and par. 61a. As repeatedly shown, and confirmed by the analysis of the authoritative contrapuntal works of Bach and other great polyphonic writers, the original source of all multi-voice music is the chord; and the prime impulse of all associated voice-movements is, obviously, the natural law of chord-succession (par. 18). For a certain period, the choice of tones and the melodic movements will be, and must be, dictated by the rules of chord-progression; the voices or parts cling, for a time, to the harmony for their support, as children (so to speak) are led by their older and stronger associates. But the time finally arrives when (in the growing experience and skill of the student) the “voices” outgrow this guardianship of fundamental harmonic law, and exercise greater independence in their movements; and, in fact, the exercise of independent melodic will may become so imperative as to reverse the conditions, so that the parts dictate the chord-successions. In other words, as the student’s command of melodic conduct increases until he can trace the course of three or more simultaneous melodic parts unerringly, so that each part by itself is a perfect melody, moments will arrive when these individual voice-movements will determine the succession of harmonic nodes, called “chords”; when, instead of the parts moving obediently towards the several harmonic points fixed by each succeeding chord (in the pre-defined order of natural chord-progression), the parts themselves assume the lead, and dictate what the chord-successions shall be. For if each part describes a faultless melodic line, and the parts harmonize, the result will be acceptable and legitimate, whether it conforms to the common law of chord-sequence or not.

For example, the chord-successions in the following examples cannot be satisfactorily defined in accordance with the common rules of chord-progression; and yet the result of the three or more associated melodies is good.

*1) “Passing-chord”; this effect is very common in Wagner.

*2) Sequence in the Alto-part. The harmonies are simple and regular, but the passing- and neighboring-notes create totally unexpected chord-effects.

When this result is achieved, the product belongs to the highest grade of polyphonic thought. But it is scarcely conceivable that this lofty phase of polyphonic effort can be often reached or long sustained; even in the works of Bach and Brahms, unmistakable evidences of emancipation from natural harmonic law are rare; in those of Beethoven and other great homophonic masters, naturally still more so. And in the more modern writings of Wagner, Rich. Strauss, and others, where such evidences are again more frequent, one cannot always quite escape an uncomfortable sensation of harmonic bewilderment. The growing vigor and independence of melodic conduct may incite to occasional successful rebellion (so to speak), but the student will never wholly outgrow the necessary and wholesome habits of harmonic action contracted during early studies. The habits formed during the discipline of deriving all melodic movements from the sub-current of natural harmonic sequence, will, in polyphonic texture of greatest power and stability, never cease to assert themselves.

Hence, the present student will apply this most eminent resource of polyphonic development chiefly as a means of defining the choice between many possible chord-structures which await each coming beat; and far more rarely, with much caution, as a legitimate device for obtaining unexpected harmonic clusters, and evolving greater freedom and opulence of harmonic movement. Review, further, pars. 59 and [par.] 60; and, particularly, pars. 61c, [par.] 61d, and [par.] 61e. Also par. 75.

134. a. The voice-movements should be conjunct, in largely preponderant measure. Skips, of course, can not and should not be avoided altogether; but they must be made with caution, and may require careful testing. They are always good when occurring within any unchanged chord, or when the first of the two tones is common to the following chord. It is best to avoid leaping to any sharply dissonant, or inharmonic, tone.

Transient harsh effects, even extreme, cannot be precluded; they are as essential in effective polyphony as are the pure consonances; but the manner of their approach and departure must be very guarded, — abrupt dissonances are usually objectionable.

b. Review, thoroughly, par. 64. It is absolutely necessary that one of the four parts should assume the lead, for a more or less extended period, — until another of their number becomes in turn the “leader.” This function devolves, naturally, upon the part which has the Theme, though not to the exclusion of some concurrent part, especially Soprano or Bass, — one of which is very likely indeed to contribute most noticeably, in this way, to the tracing of the Form.

A good illustration of this vital condition is seen in Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 22, meas. 6–12 in Soprano. See also Vol. II, Fugue 18, meas. 85–93 in Bass. Vol. II, Fugue 9, last 6 measures in Soprano.

Mendelssohn, Organ Fugue, op. 37, No. 1, — the “leading” character of the Soprano, especially, is obvious in many places; see meas. 18–19, 20–22, 41–45. Without such definite, and, if need be, lengthy melodic lines, a Fugue can hardly escape monotony, diffuseness, and vague, ineffective form.

c. For this very reason, sequences are of the utmost importance. Review par. 41c.

d. Review par. 63b and [par.] 63c; par. 75e. It is well to avoid long rests during the Exposition, until the four parts have all appeared with the Theme. Short rests are always good (Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 23, meas. 5–6); especially in the Theme itself (Vol. II, Fugue 22), or in the first Counterpoint (Vol. I, Fugue 12). And longer rests are not only permissible, but desirable, in the later course of the Fugue. It is positively unwise to keep all four parts constantly present and moving.

e. In the Exposition avoid any circumstance that tends to obscure the successive announcements of the beginning of the Theme.

Observe how effective the entrances of the parts are in Vol. II, Fugue 9 and Fugue 8. In Vol. II, Fugue 7, the last note in meas. 6 interferes somewhat with the Response in the next. Observe, further, the entrances in Mendelssohn, op. 35, Fugue 1, especially in meas. 6.

f. The character of the Subject influences its Exposition to a certain extent. A heavy Theme is somewhat likely to appear first in Bass or Tenor (i.e., low). A Theme that ends higher than it begins must appear first in a high voice, to avoid interference with its next imitation, and vice versa.

The tempo of the Subject must be taken into account also; it influences the number of parts, the number of rests, the degree of liveliness (or of stateliness) in the rhythm of the first Counterpoint, and, in fact, of the entire Fugue; and, somewhat, the number, extent, and quality of dissonances. Attention is again directed, particularly, to par. 33.

Continue the work of thorough analysis with the following sectional 4-voice Fugues:

Bach, Organ Comp. (Peters compl. ed.), Vol. III, Fugue 10; 3 sections; brief and simple, but effective; many episodes.

Vol. IV, Fugue 5; 3 sections; 5 announcements in Exposition, ending with vague cadence (meas. 20); Pedal in last section only.

Vol. IV, Fugue 9; for manual organ; 4 sections and free Coda; Counterpoint retained approximately throughout; many episodes.

Vol. VIII, Fugue 10; manual organ; very regular, “Subject” and “Response” throughout; cadences vague.

Vol. II, Fugue 10; three different thematic counterpoints, besides several incidental characteristic ones; thus:

Bach, Clavichord Works: Peters ed. 212, No. 6 (a minor). Peters ed. 216, No. 8 (p. 48); many stretti. Peters ed. 216, No. 9 (p. 52); contrary motion in middle sections, and later in alternation with the original motion.

Mendelssohn, Organ Comp., op. 37, Fugue 1; fine example of both detailed and continuous structural design; intimation of 3-Part Song-form (par. 136).

Op. 37, Fugue 2; cadences vague.

Sonata, op. 65, No. 4, last movement; Fugue with homophonic Introduction and Coda; 3 sections, cadences vague.

Sonata, op. 65, No. 5, 5th movement; Fugue; 3 Sections, cadences vague.

Mendelssohn, Pianoforte Comp., op. 35, No. 4, Fugue.

Bach, “Art of Fugue” Fugue 1; probably sectional, though the cadences are very vague, — more like one long, unbroken Section; fairly frequent episodes, based upon a brief episodic (auxiliary) motive, and corroborative of each other. Analyze this and the following very thoroughly and minutely.

Fugue 2; an Exposition, and one other long Section (cadences, if any, very vague); an auxiliary motive (meas. 8–9, Bass) and several episodic motives are utilized.

Fugue 4; five Sections, fairly definite cadences; many long episodes, based on an auxiliary figure (of two notes, meas. 14–15 in Soprano, 23–26 in Bass), and an episodic motive (of 4 tones, descending scale, meas. 18–19 in Bass); a characteristic trait of the Counterpoint (repeated measure) is also occasionally used.

Händel, Clav. Suites, No. III, second movement.

Händel, Clav. Suites, No. VIII, second movement (partly 3-voice).

Schumann, Pianoforte Fugues, op. 72; Fugue 1, five Sections and Coda; augmentation of Theme (abbreviated) in Sec. V.—Fugue 3, Romantic style, four Sections and Coda; in Sec. II an auxiliary M. appears twice (with small auxiliary figure), and reappears similarly in Sec. III; in Sec. IV there is a new and characteristic Counterpoint.

EXERCISE 39.

Write a large number of 4-voice Fugues, in sectional form; major and minor alternately; different species of measure, different style and tempo for each example.

The Song—Forms.

135. The Two-Part Song-form. The chief difference between this and the sectional design is the distinctly marked cadence (usually perfect) in or near the middle of the Fugue.

The First Part is likely to consist of the Exposition, and one additional section; the latter may be brief and largely episodic, or it may be longer and more independent; but in either case it leads into a well-prepared and fairly emphatic cadence in the Dominant key (possibly the Relative major, in a minor Fugue, or some other next-related key).

Part II is often individualized to some extent; most commonly by adopting the contrary motion of the Theme (for a time), or by means of a new and characteristic Counterpoint. At the same time, Part II may (perhaps should) exhibit more or less distinct parallelism with its First Part, — especially in its episodes; and, as usual, the last few measures may corroborate the ending of Part I. A Codetta or Coda may be added. Review par. 45.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 14; Part I (the Exposition, and 3 episodic measures) closes in meas. 20, with a strong Dominant cadence. Part II begins with Theme in Alto in contrary motion; then Theme in original motion in Soprano with disguised beginning (meas. 25), leading to cadence in meas. 28, — thus dividing the Second Part into two sections. In meas. 35–36 the episode of meas. 19 reappears, followed by Theme in Soprano. The contrary motion occurs again in Bass, meas. 32–34.

Vol. I, Fugue 17; Part I ends in meas. 16; a very faint intimation of a Third Part occurs in meas. 27.

Vol. II, Fugue 2; Part I is 3-voice texture throughout; it closes in meas. 14 with a positive perfect cadence in the Dominant key. Part II is characterized by two announcements of the Theme in Augmentation, and, further, by the addition of a 4th voice. The last 5½ measures are a Coda.

Vol. II, Fugue 7; Part I closes in meas. 30; Part II largely episodic.

Mendelssohn, Organ Fugue, op. 37, No. 3; quasi sectional,— suggestion of a separation into two Parts in meas. 32; the last 25 measures are Coda.

Organ Sonata, op. 65, No. 2, last movement; Part II characterized by a more animated counterpoint (partly thematic); few episodes until near the end.

136. The Three-Part Song-form. Part I the same as in the 2-Part Song-form. Part II is here again generally characterized in some manner; and is led into a more or less distinct semicadence upon the Dominant of the original key, usually confirmed by an emphatic (sometimes quite extended) organ-point.

Part III must be, as usual, a well-marked “Return to the beginning”; but it does not need to contain any more than the first few measures (two or three) of Part I, — enough to establish key and formal design; its subsequent contents are likely to be entirely independent, and should be more elaborate and interesting than any preceding Section; hence, stretto-imitations are peculiarly appropriate, and more brilliant (even partly homophonic) episodes are legitimate and desirable. A Coda or Codetta is frequently added. Review pars. 49, [par.] 50; also [par.] 33.

See Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 16; already cited among the sectional forms; there is a strong indication of a “Return to the beginning” in meas. 28.

Vol. I, Fugue 23; ditto; intimation of Third Part in meas. 6 from the end.

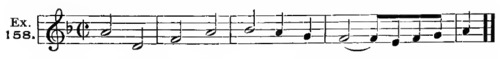

Schumann, op. 72, Fugue 4; in Part II (più vivo) two different modified forms of the Theme appear:

EXERCISE 40.

A number of 4-voice Fugues in the 2-Part and 3-Part Song-forms.

The Fugue with Special Design.

137. No good Fugue is barren of some structural design, as the foregoing paragraphs show. But it is possible to pursue some special plan in the manipulation of this polyphonic form, evolved more particularly out of the resources of its Theme, and therefore peculiarly identified with the processes of Thematic Development.

The formal plan is usually that of the sectional Fugue; and the “special design” consists in assigning to each Section in succession some specific method of thematic treatment, resulting in a systematic presentation of such possibilities of manipulation and combination as are latent within the Theme (e.g., effective stretti, contrary motion, etc.). These possibilities, or resources, are usually determined beforehand by most thorough examination and experiment with the Theme; and it is more than likely that these resources may be systematically multiplied by judicious revision and alteration of the Subject, — possibly created outright in draughting the Theme.

Review Chap. IV; especially pars. 29, [par.] 33, [par.] 36.

Analyze, most thoroughly, the following:

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 20; the “design” is strikingly manifest; Sec. I is a regular Exposition, to meas. 14; Sec. II is an equally complete Exposition of the Theme in contrary motion, to meas. 27; Sec. III is the exposition of a stretto in the 8ve after two beats (Soprano and Tenor) carried through all the parts, up to meas. 48; Sec. IV is a similar exposition of the same stretto in contrary motion (Alto and Tenor) through all the parts, somewhat abbreviated in the last measures, 62–64; Sec. V is the condensed exposition of a new stretto, after two beats in the 5th, first in original motion (meas. 64–65, Bass and Tenor), then in contrary motion (Soprano and Alto); Sec. VI, meas. 73, contains miscellaneous stretti, to the cadence in meas. 83; the rest is Coda.

Vol. II, Fugue 22, is similar; Sec. I is a regular Exposition up to meas. 25; Sec. II is the Exposition of a remarkable stretto, after one beat in the 7th (meas. 27, Tenor and Alto); Sec. III, meas. 42, is an Exposition of the Theme in contrary motion; Sec. IV, meas. 67, the same stretto as before, but in contrary motion (Alto and Soprano). Thus far, to meas. 77, the Fugue consists of two similar double-sections, one in regular and the other in contrary motion. Sec. V, meas. 80, is the Exposition of a new stretto, after one beat, in regular and contrary motion (Soprano and Tenor). Near the end, as climax (meas. 96), there is an extraordinary double-stretto, regular and contrary motion, each Theme doubled in the 3rd (the first one part of the way in the 6th).

Vol. II, Fugue 9; “Gregorian” Theme; Sec. I, Exposition; Sec. II, meas. 9, stretto in 4th after two beats (Alto, Tenor, Bass, Soprano); Sec. III, meas. 16, new stretto, in 5th after one measure (Alto, Soprano, Bass, Tenor); Sec. IV, meas. 23, new stretto, in 5th after one beat, with modified form of the Theme (Soprano, Alto, Bass, Tenor); Sec. V, end of meas. 26, Exposition of the Diminution (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass); Sec. VI, meas. 30, contains original Theme, and its Diminution, in regular and contrary motion, — faintly suggestive of Sec. I; Sec. VII, meas. 35, is substantially the recurrence of Sec. II; from meas. 38 to end is in the nature of a Coda.

Vol. I, Fugue I; the special design is not as obvious as in the above examples, but the persistent stretto-treatment of the Theme after the Exposition (meas. 7–24), especially the 4-voice stretto in meas. 16–18 (Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass), seems to be more than merely accidental.

Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Fugue 3; appears to begin with “Response,” instead of “Subject,” — (a peculiarity of irregular Exposition — par. 124 — seen also in Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. III, Fugue 4, and Vol. IV, Fugues 1 and 4).

The “Subject” (meas. 5) runs thus:

There are four Sections, separated by very vague cadences, but distinguished by their thematic contents; Sec. I is the usual Exposition; Sec. II (meas. 23) presents the Theme in the following form:

Sec. III (meas. 39) returns to the original form; Sec. IV (meas. 55) uses the following form twice,

and also the original form. The first counterpoint (partly chromatic) is retained nearly throughout.

Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Fugue 12; 4-voice; Special Design in 2-Part Song-form; Part I is a regular Exposition, with a thematic Counterpoint (par. 163) retained; Part II is an exposition of the Subject in still more richly embellished form than those illustrated in Ex. 158. The following Fugue (No. 12b) is the exact Contrary motion and Inversion of the preceding; compare them minutely.

Mendelssohn, op. 7, No. 5; very elaborate sectional form; about nine Sections (including the Exposition) and a brief Coda; Sec. III, contrary motion; Sec. IV, Augmentation; Sec. V, Diminution; Sec. VI, episodic, animated tempo and rhythm; Sec. IX, stretti.

EXERCISE 41.

Two or more Fugues with Special Design.