CHAPTER XV.

The Double-Fugue.

161. The Double-fugue is one in which two Subjects appear, and are manipulated, simultaneously.

It is not to be confounded with the forms cited in par. 52, par. 106, par. 155, and par. 157, in which two (or more) Themes are treated successively, each by itself for the time being; but takes its name from the fact that its thematic basis is a Double-theme — thematic duet.

It is not necessary that the two Subjects should always be together, for, as will be seen, either (or each) may be announced alone, or even have a separate Exposition; but, in order to achieve the idea and purpose of the Double-fugue, the Themes must appear in conjunction, distinctly, and during a reasonably extended section of the whole.

162. The Double-fugue has its inception in that variety of the single Fugue in which, as shown in par. 132, the first Counterpoint is retained, more or less persistently, throughout a part, or the whole, of the Fugue; for such companionship between the Subject and its Counterpoint approaches the effect of an intentional double thematic basis. Review par. 132, and context, thoroughly. But there still remains a characteristic difference between such examples of retained Counterpoints and the genuine Double-fugue.

163. An important intermediate grade, sufficiently independent to merit separate treatment, is

The Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint.

An ordinary contrapuntal associate of the Theme, such as is found in the majority of simple Fugues, could not be called “thematic,” even if “retained” and introduced occasionally in subsequent announcements, for the reason that it provides no especial thematic feature, does not enrich the thematic resources, and takes no active part in the development of the design.

In order to be thematic, the Counterpoint must be to a certain extent characteristic, must contain rhythmic and melodic features which distinguish it somewhat from the Theme; must recur often enough and emphatically enough to become a recognizable (though not obtrusive) line in the physiognomy of the Fugue; must influence the development, and enter actively (though not vitally, or perhaps even essentially) into the thematic texture as a whole. All this the “Counterpoint” may be, without becoming a genuine Secondary Theme, or subject to any special conditions with regard to time, place, frequency, or accuracy of recurrence.

To this class belongs, properly speaking, the example already cited in par. 132: Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 9; see Ex. 153. Also Vol. I, Fugue 14; possibly also Vol. II, Fugue 22.

More genuine examples of the Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint are the following, — to be carefully analyzed:

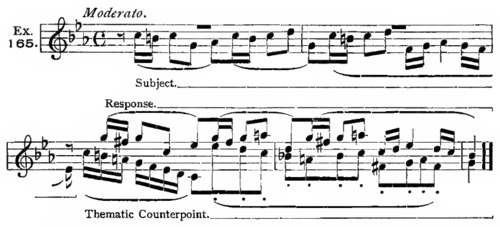

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 17; 4-voice; sectional form; Subject and Counterpoint as follows:

The Thematic Counterpoint is absent during 3 or 4 announcements of the Theme, and is often freely modified.

Further, Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. IV, Fugue 7; 4-voice; 4 sections; Counterpoint retained throughout, but modified freely. — Vol. IV, No. 10, “Canzona” (equivalent to Fugue), Division I; 4-voice; 2 sections; few episodes; Thematic Counterpoint retained, but modified.

Bach, Clavichord Comp., Peters ed. 212, No. 3; 3-to 4-voice. — In the same volume (212), No. 5, the same principle is somewhat extended, inasmuch as two different Thematic Counterpoints appear, in different rhythms; this approaches the idea of par. 179.

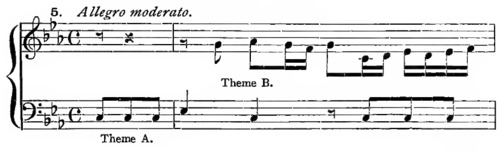

Further, Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 2; 3 voice; sectional form; Subject and Counterpoint as follows:

In order to perceive the melodic beauty and thematic validity of this Thematic Counterpoint, it should be played or sung alone. It accompanies the Theme everywhere, with but one exception (in the Codetta, last 2½ measures), and participates in all the episodes. For these reasons the Fugue barely escapes being “Double”; it would be unquestionably so were the Counterpoint more nearly coördinate, in character and importance, with the Theme proper.

To the same class, closely approximating the Double-fugue, belong Fugue 3 and Fugue 7 of Vol. I (Well-temp. Clav.); and Fugue 13 of Vol. II. — Also Partita No. 6 (Clav.), “Gigue”; large 2-Part form; Contrary motion in Part II; Thematic Counterpoint retained, but considerably changed in Second Part.

164. During the Exposition the Thematic Counterpoint appears, at each succeeding announcement of the Theme, in the part which last contained the latter; i.e., the Counterpoint follows the Theme, each time, in the same part (whether interrupted by episodes or not). After the Exposition, however, the location of the Counterpoint, like that of the Theme, is optional; and it may be occasionally omitted, or more or less modified.

EXERCISE 47.

One or two examples of the Fugue (3- or 4-voice) with Thematic Counterpoint.

The Genuine Double-Fugue.

165. In the authentic Double-fugue, the two Subjects are strictly coördinate. The secondary Theme (sometimes so called merely by way of distinction), or Counter-theme, is not a “thematic counterpoint,” but an essential part of the thematic material, subject to precisely the same specific limitations as the principal Theme.

Rule 1. Each Subject must be a perfectly good melody, in and by itself. Hence, each must be tested alone, in order to verify its individual validity as thematic sentence.

Rule 2. Each Subject must be well individualized; must differ from its fellow (chiefly as regards its rhythmic formation) sufficiently to contrast perceptibly in character, though not obtrusively. They should not begin exactly together, nor need they end upon the same beat.

Rule 3. The two Subjects must constitute peculiarly faultless counterpoint, — not by any means to the exclusion of characteristic dissonances, but without any awkward irregularities. They should not cross each other; and, as a rule, should not run much beyond an octave or tenth apart, in their original associated form, when designed for a Fugue with 4 or more parts.

Compare these rules with the primary definition of polyphony on page 1, of which they are simply a singularly severe and just exposition.

Rule 4. After the Double-subject has been completed, it must be tested in inverted form, i.e., the parts so exchanged that the upper becomes the lower. Also, though less urgently, in their joint Contrary motion.

This is necessary, not only because it is impossible to avoid Inversion, in the development of the Double-subject, but because the art of the Double-fugue consists in a great measure in these, and many similar, changes in the relations of the two Themes to each other. Review pars. 55 to [par.] 58, especially par. 57; and refer, briefly, to Artificial Double-counterpoint, par. 169, etc.

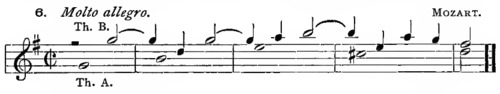

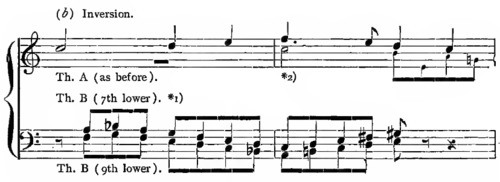

Examples of Double-subjects:

*1) The Themes are marked thus, A and B; generally in the order in which they appear, — A being the first.

*2) A fine example. Play each Th. alone.

See further, Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 12, meas. 4–6; Theme B begins with b♮ in the 3rd beat of the 4th measure. — Vol. II, Fugue 16, meas. 5–9; Theme B begins one 16th-note after A. — Fugue 18, meas. 97–101; Theme B begins on the 3rd 8th-note. — Fugue 20, meas. 3–5; Theme B commences with the 32nd-notes. — Fugue 23, meas. 27–30.

166. Double-fugues are divided into three classes or Species, according to the degree of importance assumed by Theme B.

The First Species of Double-Fugue.

167. In this Species, the two Subjects are announced together at the beginning of the Fugue.

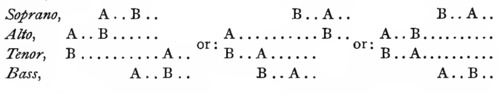

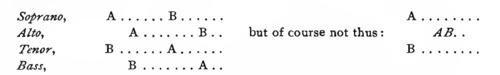

a. They may appear in any two of the parts to be employed, but are almost certain to be in neighboring parts (either the upper, inner, or lower pair). During the Exposition, for instance in 4 parts, the rules of par. 123 (which review) apply to each Theme independently of the other; i.e., each one takes its way through the four voices in the usual order. For instance (assuming them to start in the inner pair of voices):

If announced in parallel parts, a collision is possible, but always easily to be avoided. Thus:

These principles can also be readily applied to the Fugue for 3 or 5 voices.

b. After the Exposition these regulations are relaxed, as usual; the two Themes may appear in any pair of parts, in optional frequency; and, possibly, one or the other of the Themes may occasionally appear alone, though this should occur very rarely, as it militates against the specific conditions of this species of the Double-fugue. Review par. 128. Either Subject may, as usual, be slightly modified or abbreviated, as occasion or necessity arises, but not to the extent permitted with a mere “Thematic Counterpoint.”

The formal designs, and all other structural details, correspond exactly to those given in Chapters XII, XIII, and XIV.

Analyze, very minutely, the following examples of the First Species:

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. II, No. 6, Praeludium; the whole is a brilliant example of the Concert-species (par. 148), in 3-Part Song-form; Section I is a largely homophonic introduction, exactly reproduced at the end as Sec. V, or Third Part; the Double-fugue begins with Sec. II (meas. 25) and extends through Secs. II, III (Part II) and IV; it is 4-voice, and slightly irregular, as regards the order of voices, in the Exposition.

Vol. III, No. 9, Fuga, first Division; 4-voice; 2 Sections (meas. 39–63 of whole piece).

Vol. IV, No. 8, Fuga; 4-voice; 4 Sections and Coda; lengthy episodes; Theme B enters two measures later than Theme A; Exposition somewhat imperfect.

Vol. IV, No. 10, “Canzona,” Division II ( time); the First Division has already been cited as Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint; this Second Division is a Double-fugue, based upon the same Themes, rhythmically and melodically modified; form sectional, cadences vague; 4-voice.

time); the First Division has already been cited as Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint; this Second Division is a Double-fugue, based upon the same Themes, rhythmically and melodically modified; form sectional, cadences vague; 4-voice.

Bach, Clav. Duetto, No. I (Peters ed. 208, No. 4).

Bach, Clav. Toccata in d minor (Peters ed. 210, No. 4); Third Division, Presto; 3-voice, sectional, very free; the first 2 measures in lower part are introductory auxiliary tones, derived from Theme A, and frequently recurring; Theme B begins in meas. 3; another auxiliary Motive appears later. — Same Toccata, Finale; 3-voice; also very free; the first 11 measures are introductory.

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. VI, No. 18; 3-voice; per moto contrario; Chorale-fugue. — Vol. V, No. 23; 3-voice; Double-fughetta.

Händel, Clav. Suite No. 6, 3rd movement.

Beethoven, op. 120, Var. 32; 4-voice; in final sections a new thematic Counterpoint, in animated rhythm, is introduced.

Rubinstein, op. 53, No. 6; 4-voice; 3-Part form; Concert-species.

Clementi, Gradus ad Parnassum, Schirmer ed., No. 97 (orig. ed. No. 54), Fugue, with Prelude; 4-voice; contains Retrograde Imitations (par. 29b). Also No. 98 (orig. ed. No. 74); 4-voice.

Haydn, “Creation,” No. 27b, Glory to His name, and He sole on high exalted reigns. Also No. 33, Jehovah’s praise for ever, and Amen; Theme B fragmentary, and not constant.

N. B. In some of these examples Theme B might, probably, be more justly regarded as a Thematic Counterpoint only.

Händel, “Israel in Egypt,” No. 9, He smote all the first-born.

Cherubini, “Missa solemnis,” Cum sancto spiritu. Also Amen of the Credo.

Mozart, “Requiem,” No. 1, Kyrie; reproduced as Finale, with different text.

EXERCISE 48.

A. Invent a large number of Double-subjects, in various styles, tempi, keys, and modes.

B. Write two 2-voice Inventions, with Double-subject, 1st Species. Models for this work will be found in Bach, 2-voice Inventions, Nos. 5, 6, 9, 11, 12, and 15; and Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Prelude 3; Vol. II, Prelude 20; analyze thoroughly.

C. Two Double-fughettas (one or two Sections), major and minor respectively; 4-voice and 3-voice.

D. Two complete Double-fugues, 1st Species, 3-, 4-, or 5-voice; for Pianoforte, Organ, String-quartet, or Vocal parts.

The Second Species of Double—Fugue.

168. In the Second Species, Theme B enters as first contrapuntal associate, in connection with the second announcement of Theme A (i.e., with the first “Response”). It therefore corresponds, in this respect, to the Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint; but all the conditions detailed in par. 165 must be strictly observed.

The order of voices during the Exposition is simpler than in the First Species, because Theme B naturally (and almost invariably) follows Theme A in the same voice,— precisely as shown in Exs. 164, [ex.] 165, excepting that the contrapuntal associate is a genuine Counter-theme, and not merely a thematic counterpoint. But, as Theme A thus appears once alone, the Exposition is generally extended by one extra announcement, in order that Theme B may appear in every part; i.e., in the 4-voice Fugue the Exposition usually embraces five announcements of Theme A, the 5th time in the voice which began the Fugue.

See Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 12; Theme A is announced in Tenor, then in Alto (meas. 4), Bass (meas. 7 — this is irregular — par. 124), Soprano (meas. 13), and again in Tenor (meas. 19); Theme B follows, each time, in the same voice; the Exposition closes in meas. 22. Exactly the same in Vol. II, Fugue 16, in every particular, excepting that the order of parts is regular; the Exposition closes in meas. 24. — In Vol. II of the Org. Comp., Fugue 9, the Exposition is not thus extended.

The distinction between the 1st and 2nd Species is limited, thus, to the Exposition alone. The subsequent development is identical. Analyze, very carefully, the following; observe, here again, the degree and quality of freedom of detail exercised, and endeavor to recognize the factors that must be regarded as vital and inviolable:

Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. I, Fugue 12; 4-voice, sectional; the 6 tones immediately following the cadence of Theme A (meas. 4, beats 1 and 2) are intermediate — see par. 121b; they constitute the staple of all the episodic passages, which are of frequent and very regular occurrence throughout this Fugue; Theme A appears alone in meas. 40–43. — Vol. II, Fugue 20; 3-voice, sectional.

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. II, Fugue 9; 4-voice; definite 3-Part Song-form, Part III an exact reproduction of Part I, modified only at beginning; Concert-species; many brilliant episodes, in animated rhythm. — Vol. III, Fugue 7, first Division; 4-voice, sectional.

Bach, Clav. Comp. (Peters ed. 211, No. 1), Fugue, with Toccata; 4-voice, sectional, regular and simple; Contrary motion frequent.

Duetto No. IV (Peters ed. 208, No. 4); 2-voice, sectional. — Toccata in f minor (Peters ed. 210, No. 2), Division IV,  time; 4-voice, sectional. — Partita No. VI, “Toccata”; 3 Divisions, embracing the Double-fugue (3-voice, sectional) between a thematically related Prelude and Postlude. — (Same Partita, “Gigue”; already analyzed, as Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint).

time; 4-voice, sectional. — Partita No. VI, “Toccata”; 3 Divisions, embracing the Double-fugue (3-voice, sectional) between a thematically related Prelude and Postlude. — (Same Partita, “Gigue”; already analyzed, as Fugue with Thematic Counterpoint).

Händel, Clav. Suite No. II, Finale.

Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. VII, No. 47; Fugue with Chorale; 4-voice; cantus firmus in Bass. — Vol. V, No. 39; chorale-fughetta, 3-voice.

Händel, “Messiah,” No. 23, And with His stripes. — “Samson,” No. 9, Part II, Was ever the most High.

Bach, “B-minor Mass,” No. 4, Et in terra pax.

EXERCISE 49.

A number of Double-fugues, 2nd Species; 3-, 4-, or 5-voice; different character and tempo; instrumental or vocal. Some of the Double-subjects of Exercise 48A may be utilized.

Artificial Double-Counterpoint.

169. The term “artificial” is adopted (in its most serious sense) in distinction to “natural,” with reference to those varieties of Double-counterpoint in which the harmonious result is not a matter of course, but must be assured by calculation. Review par. 55.

As stated in pars. 55 and [par.] 56, when the Double-counterpoint is obtained by inversion in the 8ve, no change of interval-relations takes place, and an equally harmonious agreement results, naturally. But no such natural guarantee exists when any other interval of inversion is used. Therefore, Double-counterpoint in the 8ve, without any other modification, is the only Natural kind, while Double-counterpoint in any other interval, or with any other modification of either part, belongs to the Artificial kind, and is to be determined only by calculation or experiment.

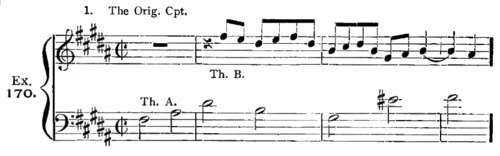

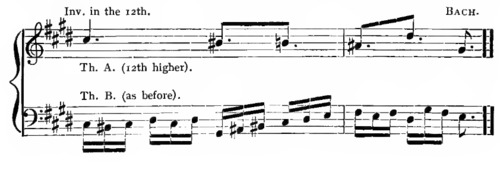

170. Double-counterpoint in the Twelfth. Double-counterpoint is obtained by transferring one part towards and past the other; and the species is defined by the interval of inversion involved. For example, if the lower part remains, and the upper part is shifted downward a 12th (an 8ve and a 5th, or perhaps two 8ves and a 5th) the result is Double-counterpoint in the 12th. For illustration:

(a) The Original Counterpoint.

(b) Inversion in the 12th (affecting Th. A).

*1) Theme A is shifted up, past its fellow, a 12th; Theme B remains where it was.

*2) Such modifications as this (f changed to f♯ by the accidental) are often absolutely necessary, and are to be freely employed, with discretion, in favor of better modulatory agreement. Their use is entirely legitimate, inasmuch as the two forms (the Original and the Invention) never appear together. The change, however, may only affect the accidental, — never the letter.

An apparently new result is obtained by moving the other Theme down, past its fellow, a 12th. But this, or any other movement of both parts together, equivalent to the 12th, represents simply a transposition of the Inverted form. Thus:

(a) Inversion in 12th (affecting Th. B).

(b) Inversion in the 12th (affecting both Themes).

171. The invention of a Double-subject (or any two-voice-sentence) which may thus submit to Inversion in the 12th — or any other interval excepting the 8ve — is so largely a matter of incessant experiment, tone for tone, that scarcely any valid rules can be given. At the same time there is a certain device for each separate species of Double-counterpoint, which systematizes and simplifies the formation to some extent.

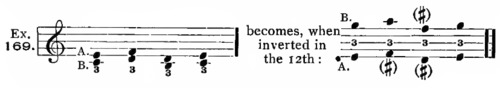

The device for Double-counterpoint in the 12th consists in the frequent use of the interval of a 3rd (or 10th) in the Original form; for this interval, when inverted in the 12th, results again in a 3rd; for example:

This point, and others, are illustrated in the following:

*1) That is to say, the same tones (letters) as before. The change of register makes no difference, as long as the parts pass each other, in the stipulated interval.

*2) From the orchestral Variations upon a Theme by Haydn, op. 56, Var. IV. See also the next 20 measures, which are followed by a similar exact Inversion in the 12th.

See also Bach, “The Art of Fugue,” Fugue 9: Original counterpoint in meas. 35–43 (Soprano and Tenor); Inversion in the 12th in meas. 45–53 (Tenor and Alto). Same work, Canon IV; Original counterpoint in meas. 9–35; Imitation in 12th in meas. 42–68 (the upper part is shifted down a 12th, while the lower part retains the same tones, shifted up two octaves); a long and instructive example, to be carefully analyzed.

172. Double-counterpoint in the 11th. Frequent use of the interval of a 6th will, as a rule, yield a good Inversion in the 11th (the 6th becoming again a 6th). For example:

This species, Double-counterpoint in the 11th, is the companion (the counterpart) of that in the 12th; and, because of the harmonic similarity between the 6th and the 3rd, is scarcely distinguishable from it. One is, technically speaking, simply the 8ve-inversion of the other. For illustration: invert the parts in Ex. 167a (in the octave), and also invert Ex. 167b in the same manner; upon comparing the two results with each other they will be found to constitute Double-counterpoint in the 11th.

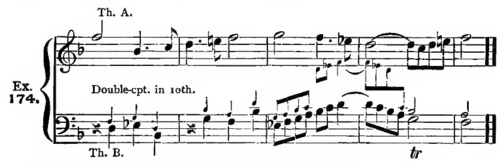

173. a. Double-counterpoint in the 10th. The best device for Double-counterpoint in the 10th consists in doubling one of the Themes in the 3rd, and counterpointing the other Theme against this double line. In order to yield counterpoint in the 10th, the duplication must fall between the principal lines as a so-called inner 3rd; i.e., it must be the lower third of the upper voice, or the upper third of the lower. Thus:

*1) The large notes constitute the Original counterpoint; the inner part (small notes) is a duplication of the upper Theme in the lower or inner 3rd, in order to provide for Double-counterpoint in the 10th by inverting the parts, thus:

b. Although Double-counterpoint always implies Inversion of the parts (as stated in par. 55), it must be understood that the principle is the same whether the Inversion actually takes place or not; and therefore Ex. 172 is as certainly Double-counterpoint, with its duplication of one part in the 3rd, as Ex. 173, or any other of the inverted forms.

c. Such a duplication in the 3rd is less difficult and hazardous than might be suspected, and will quite frequently be found practicable with little or no change, in any ordinary counterpoint. The only necessary condition or limitation is, that the parts shall move in contrary directions (at those points where both are moving). This may be verified in Ex. 172. It is applied, with precisely equal certainty, to the other part (Theme B) of the above example, by Bach himself. Thus:

[Audio: First the original counterpoint, then double-counterpoint at the tenth]

N.B. Each lower part alone must be valid with the upper.

d. Further, exactly the same result is obtained by duplicating either part in the outer 6th (instead of inner 3rd, as in Exs. 172 and [ex.] 174). Thus:

[Audio: First the original counterpoint, then double-counterpoint at the tenth]

N. B. Play each duplicated part alone with the other. And write out the Inverted forms of each example, complete, as in Ex. 173.

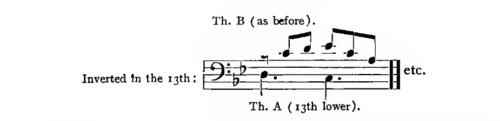

174. Double-cpt. in the 13th (or 6th). This is the companion-species of that in the 10th, and is obtained by duplicating either Theme in the outer 3rd (comp, par. 173a), or inner 6th (par. 173d). For example:

[Audio: First the original counterpoint, then double-counterpoint at the 13th]

N. B. Play each upper part alone with the other. Write out the example also with duplication of the lower part in the outer (i.e., lower) 3rd. Write out each example in its Inverted form, complete.

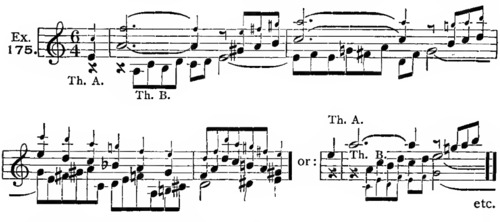

175. It is sometimes possible to apply the device of duplication in the 3rd (or 6th) to both parts at once. Thus:

[Audio: First the original counterpoint, then double-counterpoint in small notes]

*1) Slightly changed from the Original (Bach, Well-temp. Clav., Vol. II, Fugue 16, meas. 59–63). Comp. with meas. 9–13; and see, also, meas. 45–49; 51–55; 69–73.

The complication of Double-cpt. “Species” involved in such twofold duplications can be defined only by reference to the Original form (here shown in large notes): it is exceedingly confusing, — and no doubt wholly unnecessary.

A long and instructive example of Double-counterpoint in the 10th may be found in Bach, “Art of Fugue,” Canon III; meas. 5–39 are inverted in the 10th in meas. 44–78; the lower part one 8ve higher, and the upper a 10th lower, than before.

Bach, 3-voice Inv. No. 8, meas. 17–18; upper, part duplicated in the inner 6th.— Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 22, meas. 6–3 from the end (double duplications, partly in 6ths, and partly in 3rds). — Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. VI, No. 18, meas. 22–23; Theme A in Bass, Theme B doubled in 3rds, slightly embellished, in upper parts.

176. Double-cpt. in the 9th, and its companion, in the 7th. For these extremely difficult and rare species there is no other guide than the rigid application of the two general principles, of (1) stepwise progression and (2) contrary direction. For example:

[Audio: Double-counterpoint at the 7th]

[Audio: Double-counterpoint at the 9th]

[Audio: Double-counterpoint at the 7th and 9th together]

*1) Theme B is written out in both species of Double-cpt. at once, in this instance, because they produce, together, a somewhat fuller and more plausible harmonic result than either would alone. This, however, is not (or should not be) necessary.

*2) The addition of another part, as here, is often of the utmost consequence in defining more fully the harmonic intention.

A double-subject, devised thus strictly in contrary directions, and with exclusive stepwise progressions, will generally prove available for every species of Double-cpt. That is the case with Ex. 178, as the student may (and should) verify.

Other Varieties of Artificial Double-Counterpoint.

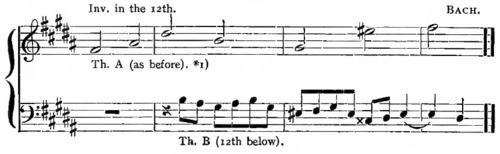

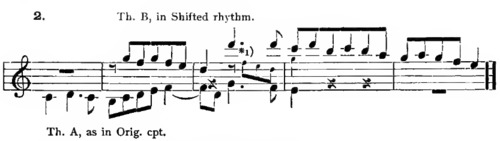

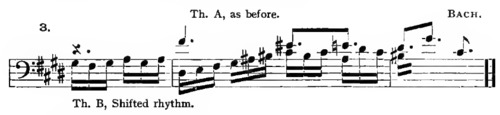

177. These are purely experimental, and cannot be obtained by any method of calculation. They consist in multiplying the relations of the two Themes to each other by applying the ordinary modifications (Contrary motion, Shifted rhythm, Augmentation, or Diminution) to either Theme alone, while the other retains its original form. For illustration, Ex. 167 chances to admit of transformation as follows:

And Ex. 170, No. 2, reappears later thus:

*1) See Ex. 178, Note *2).

See further, Bach, 2-voice Invention No. 11; Original cpt. in meas. 1–2, Theme A in upper, Theme B in lower part; inverted in meas. 3–5, Theme A as before, but in lower part, Theme B in upper part in Contrary motion and Shifted rhythm. — Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 23; comp. meas. 60–63 with meas. 27–30 (Theme B in Shifted rhythm).

EXERCISE 50.

A. A number of Double-subjects in Double-cpt. in the 12th (par. 171). Each example is also to be written out in the 8ve-Inversion, and in complete Contrary motion (i.e., both Themes together in Contrary motion). See par. 165, Rule 4.

B. Double-subjects in Double-cpt. in the 11th (par. 172). Each to be subjected to the same Inversions as at A.

C. The same in Double-cpt. in the 10th (par. 173a-c).

D. The same in Double-cpt. in the 13th (par. 174).

E. The same in Double-cpt. in the 9th, — and in the 7th.

F. The Double-subjects invented in Exercise 48A are to be subjected to very thorough experimental tests, with reference to the duplication of either, or both, of the Themes in the inner, or outer, 3rd.

G. All of the above Double-subjects (including Exercise 48A) are to be exhaustively examined with reference to the experimental species of Artificial Double-cpt., illustrated in par. 177.

The Third Species of Double-Fugue.

178. In this species, which may be regarded as the most genuine and distinctive of the Double-fugue, the entire Exposition (first section) is devoted to Theme A alone. And, in the broader Song-forms, this Exposition may be extended a section or more, so as to complete the measure of a full First Part.

The following sections or Parts may then be designed in either of two ways:

(1) Theme B may simply join Theme A, so that they appear in conjunction the rest of the way; or (2) Theme B may also be first manipulated alone, for one section or Part, and the conjunction of the two Subjects follow in the final Sections, or Third Part.

In the latter case, where each Subject is manipulated alone before they appear together, care must be taken to avoid contrapuntal associates that resemble the other Theme too closely, especially with regard to their rhythmic formation; otherwise the subsequent conjunction of the Themes will not be striking enough, and the product may be monotonous.

An incipient type of the first class is shown in par. 142, which review.

The first class is illustrated in the following (to be thoroughly analyzed):

Bach, “The Art of Fugue,” Fugue 9; 4-voice; 3 Sections, cadences vague; Theme A alone to meas. 34; A and B together from meas. 35 to the end. Contains Double-cpt. in the 12th. — Same work, Fugue 14; 4-voice; Theme A alone to meas. 21; A and B together from meas. 22 to the end; in Section III (meas. 34) there is a regular Exposition of an auxiliary Motive, derived from the first Counterpoint (meas. 6–7); in Sec. V (meas. 67) another brief auxiliary Figure appears. Contains Double-cpt. in the 10th and 12th.

The second class is illustrated in the following:

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 18; 3-voice; 3-Part Song-form; Theme A alone to meas. 60; Theme B alone from meas. 61 to 96; A and B together from meas. 97 to end. The first counterpoint differs but little from Theme B, but the latter is nevertheless characteristic enough.

Vol. II, Fugue 4; 3-voice; Theme A alone 10 meas. 19; in meas. 20–21 Theme B is introduced tentatively, once (in upper part), and in modified form; meas. 24–29 Theme A again alone, Exposition of Contrary motion; in meas. 30 Theme B is again “attempted” (lower part) in still another modified form; meas. 35–39 Theme B, in correct form, has a regular Exposition alone; A and B together from meas. 48 to end. Artificial Double-cpt. freely applied.

Bach, “The Art of Fugue,” Fugue 10; this is practically the same as Fugue 14 (analyzed above), with which it must be very carefully compared; it differs from No. 14 in containing an additional first Section (meas. 1–22), devoted to the Exposition of Theme B; i.e., it begins with the “secondary Subject”; thereafter it corresponds very closely to No. 14. Hence it contains: Theme B alone in Sec. I, Theme A alone in Sec. II, both together the rest of the way. The Subjects are well contrasted.

Bach Org. Comp., Vol. IV, No. 6; 4-voice; 3-Part Song-form; Theme A in Part I Theme B in Part II, both together in Part III; the last 14 measures are an independent Postlude, quasi free Fantasia. The Pedal announces both Themes almost invariably in simplified rhythmic form; frequent perfect cadences in course of the Sections; few episodes until near the end. Themes well contrasted.

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Prelude 7; 3 rhythmically contrasted Divisions; texture more free than in the genuine Double-fugue.

Mendelssohn, Pfte. Comp., op. 35, Fugue 4; 4-voice; 3-Part Song-form; Theme A in Part I, to meas. 46; Theme B alone to meas. 96, often in modified form; A and B together, with some freedom of treatment, from meas. 97 to end. Themes rhythmically contrasted.

Analyze, further, the following miscellaneous examples (irrespective of class):

Bach, Partita (Clav.) No. 5, “Gigue”; large 2-Part form, Gigue-species.

Bach, Clav. Comp., Toccata in c minor (Peters ed. 210, No. 3); Divs. I and II are introductory; Div. III, lengthy Exposition of Theme A (3-voice, Concert-species); a brief interlude follows, and then Div. IV, with Themes A and B together. — Fantasia e Fuga in a minor (Peters ed. 208, No. 2); excellent example; 4-voice; 3-Part Song-form.

Mozart, String-quartet (Peters ed. 1037a), No. 1, G major, Finale; Double-fugue in homophonic surroundings (as Sonata-movement). Regular Exposition of two different Subjects, one at the beginning, and the other 30 or 40 measures later; both together in final Division (the “Recapitulation “).

Raff, Pfte. Suite, op. 69, Finale.

Saint-Saëns, Pfte. Etudes, op. 52, No. 3, Fugue with Prelude; only a very concise Exposition of Theme B, and no more than brief fragmentary conjunction with Theme A, in last Section.

Rubinstein, Pfte. Fugues and Preludes, op. 53. Fugue 1, 3-voice.—Fugue 4, 4-voice; 5-Part Song-form;* contains Contrary motion, and Augmentations.

*Homophonic Forms, Chap. XVI.

Händel, Clav. Suite IV, first movement; 4-voice.

Vocal: Händel, “Israel in Egypt,” No. 11, Egypt was glad (Fugue in Contrary motion). — The same, No. 21, And I will exalt Him, and I will exalt Him.

Mendelssohn, “St. Paul,” No. 22; Sing His glory, and Amen.

Bach, “B-minor Mass,” No. 19, Confiteor, and In remissionem; near the end a Cantus firmus is interwoven, first in canonic imitation, and then single, in Augmentation.

Irregular (4th) Species of Double-Fugue.

179. An irregular variety of the Double-fugue, which might be designated as the 4th Species, consists of one principal Theme, with two or more contrasting thematic Counterpoints, one or the other (or all) of which may assume the importance of a genuine secondary Theme.

The thematic Counterpoints (or Counter-themes) are likely to appear in successive sections, or Parts, of the usual forms.

Analyze, thoroughly, Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. II, Fugue 23; 4-voice; the first 27 measures are an Exposition of the principal Subject, with a characteristic thematic counterpoint, appearing first in meas. 5–8 (Bass); after meas. 27 it is permanently abandoned. In Part II (meas. 27–74) a second thematic counterpoint, or, rather, a genuine Counter-theme, appears, first in Soprano; in meas. 60–62 it is shifted backward a half-measure (par. 177); and Double-cpt. in the 12th abounds throughout. At the beginning of Part III (meas. 75) Theme A occurs once alone.

This example resembles those of par. 142 (which see), but is more nearly a genuine Double-fugue.

See further, Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. III, Fugue 1; 5-voice; 3 distinct Divisions, — somewhat like the Fugue-Group (par. 157); Div. I,  time, Exposition of principal Theme; Div. II,

time, Exposition of principal Theme; Div. II,  time, contains an Exposition of the First Counter-theme alone, in slightly modified form, and the conjunction of this with the principal Theme (rhythmically modified on account of the change in measure); Div. III,

time, contains an Exposition of the First Counter-theme alone, in slightly modified form, and the conjunction of this with the principal Theme (rhythmically modified on account of the change in measure); Div. III,  time, consists in a similar Exposition of the Second Counter-theme alone, and its conjunction with the principal Theme, again with modified notation. Analyze minutely, and compare with the next-following Fugue.

time, consists in a similar Exposition of the Second Counter-theme alone, and its conjunction with the principal Theme, again with modified notation. Analyze minutely, and compare with the next-following Fugue.

Vol. III, Fugue 2; 4-voice; 3-Part Song-form; the First Counter-theme is associated with the principal Theme in Sections I and II (to meas. 70) as a Double-fugue of the 2nd Species; the Second Counter-theme has an independent Exposition in meas. 70–128, as Part II; Part III begins with one conjunction of the First Counter-theme with the principal Theme, but consists thereafter of the association of the latter with the Second Counter-theme. Neither of these examples must be confounded with the Triple-fugue (par. 180), for nowhere are all three Subjects combined.

Bach, Clav. Comp. (Peters ed. 212, No. 5); 4-voice; two different thematic Counterpoints, in different rhythms, and slightly modified, — i.e., not genuine Counter-themes.

Raff, Pfte. Suite, op. 91, first movement; elaborate Introduction, as Fantasia; first announcement of Fugue-subject interwoven with last vanishing chords of the Introduction; two different thematic Counterpoints, in accelerated rhythms.

Beethoven, “Mass in D,” op. 123, Et vitam venturi; two different Counter-themes.

EXERCISE 51.

A. A number of Double-fugues, 3rd Species, 3, 4, or 5 parts, for pianoforte, organ, string-quartet, or vocal parts. Any Double-subject of former Exercises may be used, preferably those of Exercise 50, with a view to manipulation in both Natural and Artificial Double-cpt.

B. One or two Double-fugues of the 4th Species, according to par. 179.