CHAPTER XVI.

The Triple-Fugue.

180. The Triple-fugue is based upon three different coördinate Themes, which appear together, as a threefold Subject, during some portion of the composition.

All the rules of par. 165 apply strictly, and must be reviewed. The chief difficulty in devising a Triple-subject is, so to individualize each one of the three Themes that it constitutes by itself a wholly independent and characteristic melody, especially in its rhythmic formation; and that, furthermore, each one may serve equally well as Soprano, Bass, or inner part. Compare par. 57.

Probably the best plan is to follow the principle of par. 61b (which review), i.e., to invent the Themes successively; first, Theme A, in stately rhythm (preponderantly [whole] and [half] - notes); then to add Theme B to this in more animated rhythm ([quarter] - notes), and then Theme C to these, in still another form of more active rhythm. This is, however, by no means imperative.

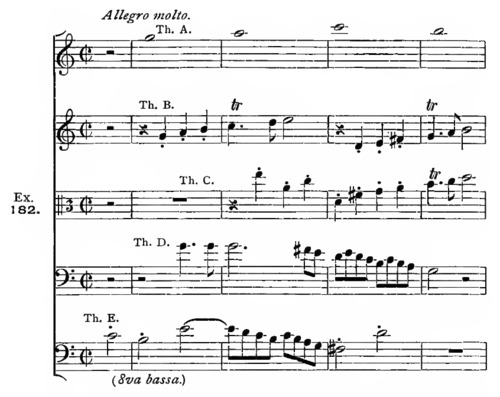

Illustrations of the Triple-subject:

*1) Themes A and B end here, while Theme C runs on a few beats. In the other illustrations it will be seen that the 3 Themes usually close exactly, or nearly, together. But observe that they do not begin together.

*2) From the String-quartet, op. 18, No. 4, second movement, meas. 64–68 from the Double-bar.

See also Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 9, meas. 3–4.

Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Prelude 19, first 2½ measures. — Vol. I, Fugue 4, meas. 51–54 (Tenor, Bass, Soprano). — Vol. I, Fugue 21, meas. 9–12.

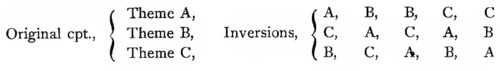

181. The Inversion of a Triple-counterpoint yields a fivefold result (or 6 forms in all), thus:

a. As in Double-cpt., it is generally a foregone conclusion that the 8ve-inversions will all be possible (par. 56), though some embarrassment, with regard to register, may be encountered; and it may be necessary at times both to cross the parts and to allow them to diverge widely.

b. On account of the multiplied complications, only the Natural species (8ve-inversion) need claim attention. The Artificial species are exceedingly difficult to obtain, though sometimes one or another of the devices shown in par. 173 and par. 177 may be ferreted out by patient and exhaustive experiment.

*1) Each Theme starts with the letter a 4th above the original first tone, Theme A being transferred to a lower, B and C to a higher register.

*2) Each Theme in the 7th of the original counterpoint, excepting the first tone of Theme B. The counterpoint is therefore in each case Natural Species.

See Beethoven, Pfte. Sonata, op. 2, No. 3, Finale, meas. 55–62; very simple.

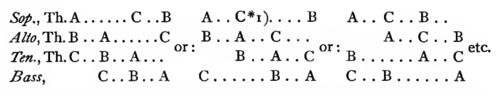

182. The Triple-fugue, like the Double, may also be divided into three Species.

In the First Species, all 3 Subjects are announced together at the outset, and the order of voices during the Exposition is to be defined strictly according to par. 167a; that is, each Theme passes from part to part in the established order (par. 123), independently of the others — common sense being employed to avoid collisions. For example (4-voice):

*1) Theme C in Soprano following C in Bass. This is not passing to the “next higher or lower voice,” it is true; but it is equivalent, because these are not parallel voices.

Irregular Expositions are not uncommon. See also par. 167b,

Analyze, thoroughly, Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Prelude 19; 3-voice; the first tone in Bass is auxiliary; the Triple-subject is 2½ measures long; the design is 3-Part Song-form; Part I is a regular Exposition, to meas. 12; Part II (meas. 12–17) begins with the original counterpoint; Part III (end of meas. 17) contains two announcements.

Beethoven, String-quartet, op. 18, No. 4, second movement, measures 64 to 81 from the Double-bar; original counterpoint given in Ex. 180, No. 2; a complete Exposition, 4 announcements.

183. In the Second Species, Themes A and B begin together, and Theme C follows immediately (usually in one of the same voices).

See Bach, 3-voice Invention No. 9; Theme A in inner, B in lower part; the first Bass note is auxiliary; in meas. 3, Theme A appears in the upper, B in the inner, and C is added to these in the lower voice; the form is sectional; analyze thoroughly.— Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. I, “Passacaglia,” Finale; 4-voice, sectional (quasi 3-Part form); Exposition to meas. 29, with brief cadence in meas. 21, contains 5 announcements, in order that each part may exhibit all three Themes; Theme C occasionally modified at its end.— In Vol. II, Fugue 4, there are many passages in Triple-cpt., and even some evidences of Triple-fugue design. — Vol. VIII, No. 12; 4-voice; sectional; somewhat irregular.— Beethoven, 3rd Symphony, Adagio, measures 10–29 from second change of signature (i.e., back to 3 flats); Theme A in half-notes, and B in quarters and eighths, together in Viola and 2nd Violin; followed immediately by Theme C, 16th-notes, in 2nd Violin; a complete Exposition, 5 announcements.

A sub-variety of the Second Species is illustrated in Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 21; the 3 Subjects enter successively (in closer analogy to the 2nd Species of the Double-fugue); 3-voice; sectional; Theme C, meas. 9–12, in upper part, is very fragmentary, but thoroughly characteristic and persistently retained (with slight modifications).

Also Brahms, Fugue with Chorale (O Traurigkeit) for organ, in a minor; chorale in pedal-bass; Theme A derived from first Line of chorale; per moto contrario throughout (par. 158); orig. cpt. given in Ex. 180, No. 4.

184. In the Third Species, Theme A is manipulated alone during the whole Exposition, or Part I; thereafter, several different designs are possible and equally legitimate. For example, — among many possible arrangements, in successive Sections (or Parts):

| Theme A alone. | B alone, or A and B together. | C alone, or A and C together, or B and C together. | A, B, and C together. |

Analyze diligently Bach, Well-temp. Cl., Vol. I, Fugue 4; 5-voice, Two-Part form; Theme A alone in Part I (to meas. 35); Theme B begins with Part II, in Soprano, as counterpoint to Theme A in Tenor; after one other announcement of A and B (meas. 44), Theme C joins them, in meas. 49, Tenor; the 3 Themes are then developed pretty steadily together to meas. 81–84, whereupon Theme B gradually withdraws entirely, leaving the rest of the Fugue to A and C; these, in meas. 94, begin a series of extremely powerful stretto-announcements together, extending nearly to the end. — Vol. II, Fugue 14; 3-voice, Two-Part form; Theme A alone in Part I (to meas. 20); Theme B then follows, in Bass, slightly modified at its end, and is manipulated alone, in somewhat abbreviated stretti, to meas. 28; at the end of meas. 28 Theme A appears (inner voice), Theme B following in Bass two measures later; in meas. 36 Theme C enters (inner voice, 16th-notes), and is developed alone to meas. 51; after one announcement of A alone (meas. 52–54, inner voice), the 3 Themes are combined (A at end of meas. 54 with disguised beginning, upper voice, — C in next measure, Bass, — B in meas. 56, inner voice), and remain together to the end.

Bach, “The Art of Fugue,” Fugue 8; 3-voice, sectional; design as follows (Themes named A, B, and C, in the order of their appearance — C being the principal Subject): Sections I and II, Theme A alone; Sec. III (meas. 39) and IV, Themes A and B; Sec. V (meas. 94), Theme C; Sec. VI, (meas. 125), Themes A and B; Sec. VII (meas. 147), Themes A, B, and C. Compare carefully with same work, Fugue 11. The latter uses the same Themes as No. 8, but begins with the principal Theme; further, the Themes are all in the Contrary motion of the former. It is much longer and more elaborate, introducing a characteristic chromatic counterpoint (to one of the secondary Themes) which is retained and much used,— almost as 4th Theme (meas. 28–29), though all four do not appear anywhere together, thus escaping the design of a Quadruple-Fugue (par. 185). The design is as follows (Themes named as in No. 8): Sec. I, Theme C; Sec. II (meas. 27), Theme A, with thematic counterpoint “D”; Sec. III (meas. 71), Theme C in Contrary motion; Secs. IV (meas. 89) and V, Themes A and B (also two isolated announcements of C); Sec. VI (meas. 146), Themes A, B, and C to the end. — Same work, Fugue 15; the 3 Themes are strikingly contrasted in rhythm and character (the third one based upon the notes “b-a-c-h“). This Fugue was interrupted by the master’s death, after the Exposition of the 3rd Theme, and before all three Subjects were united. — Bach, Org. Comp., Vol. VI, No. 31; chorale as Fugue-group (par. 155); 4-voice; cantus firmus in Bass; new Theme for each Line; Double-cpt. during first Line; Triple-cpt. in all following Lines. — Thiele, Fugue (with chromatic Fantasia) for organ; 4-voice; Theme A alone, then A and B together, and then all three. — Brahms, Fugue in a♭ minor for the organ; 4-voice; sectional; Thematic Counterpoint in first Sections; stretti, augmentation, diminution, and shifted rhythm in final section; all per moto contrario. A superb masterpiece, worthy of most diligent analysis.

Quadruple and Quintuple Counterpoint.

185. The invention and employment of a complex of more than three Subjects, for the Fugue-form, is so difficult and of so little practical effectiveness as to be naturally very rare; and even for technical discipline it is of but limited value.

Brief examples of good 4- or 5-voice counterpoint with well-contrasted, independent parts, may be introduced episodically in the course of a Fugue, and reproduced in inverted forms (in 8ve-cpt. only) with good results.

A brilliant specimen of Quintuple-cpt. may be found in Mozart, Symphony in C major (sometimes called the “Jupiter” symphony), Finale. The complex of 5 Subjects, which first appears in meas. 40 from the end, is as follows (in the orchestral String-quintet):

This is followed by a complete Exposition, 5 announcements in all, up to meas. 22 from the end. But this is not all; the entire Finale is, in fact, a Quintuple-Fugue of the 3rd Species, molded in the form of the “Sonata-Allegro,” and so designed that nearly all of the Subjects appear successively, and are manipulated, alone or together, in stretti, contrary motion, diminution, and even retrograde imitation, before their ultimate conjunction in the final Coda. Analyze thoroughly, from the orchestral score.

In conclusion, the student is recommended to analyze the 48 Fugues of A. A. Klengel (“Canons and Fugues in all the keys”; 2 vols., Breitkopf & Härtel ed.). This distinguished and interesting work, to which frequent reference will be made in the next Division, has been intentionally omitted in the preceding pages, in order to provide opportunity for an extended course of independent analysis. The Fugues are almost exclusively “Single”; Contrary motion, Stretti, Augmentation, and Diminution abound, and even Retrograde Imitation occurs in one instance (in the unique 2-voice Fugue, Vol. I, No. 16).

EXERCISE 52.

A. Invent a number of Triple-subjects, in various styles, and write out all five 8ve-inversions of each.

B. Two brief Triple-fugues, or Fughettas, one in the First, the other in the Second Species, major and minor.

C. Two or three complete Triple-fugues, Third Species.

D. A few experiments in Quadruple- and Quintuple-counterpoint, with Inversions (as explained in pars. 180–[par.] 181).